Octa Clark Interview

And you take Joe Falcon, was very good too. And Amédé Breaux was very good too. Amédé Breaux was good too. He was first a singer and he was good, too. A lot of people were good, but some like Aldus Roger, you going to hear him. He’s a good playing, but an old musician told me. He said, “Clark, nobody can beat you for dance.” I said, “You believe so?” He said, “Yes.”

– Octa Clark

- Octa Clark Interview 00:00

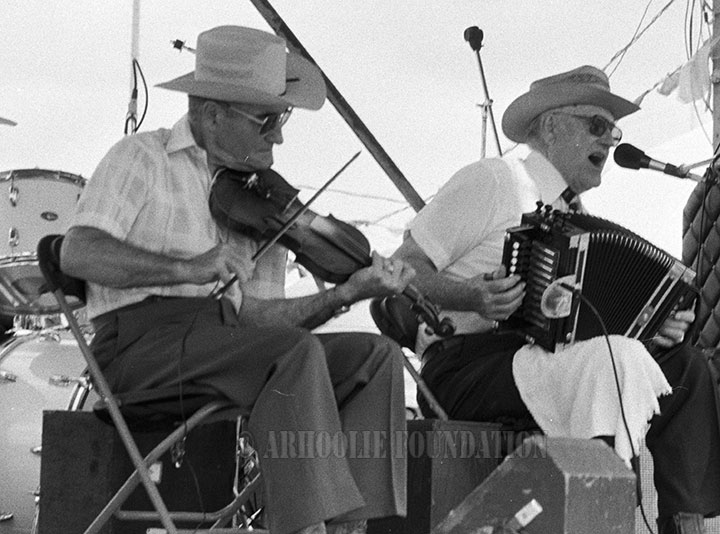

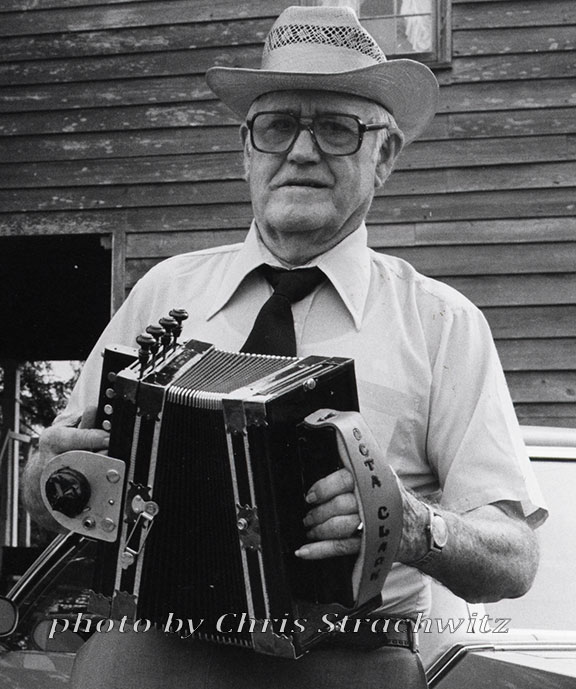

Interviewee: Octa Clark

Interviewer: Chris Strachwitz and Michael Doucet

Date: May 19, 1981

Location: Louisiana

Language: English and French /Français

To learn more about Octa Clark, listen to his interview in the Ann Savoy Collection

This is an interview originally recorded for research purposes. It is presented here in its raw state, unedited except to remove some irrelevant sections and blank spaces. All rights to the interview are reserved by the Arhoolie Foundation. Please do not use anything from this website without permission. info@arhoolie.org

Some interviews contain potentially offensive language, including obscenities and ethnic or racial slurs. In the interest of making this material fully available to scholars and the public, we have chosen not to censor this material.

Octa Clark Interview Transcript:

A Note About the Transcriptions: In order to expedite the process of putting these interviews online, we are using a transcription service. Due to the challenges of transcribing speech – especially when it contains regional accents and refers to regional places and names – some of these interview transcriptions may contain errors. We have tried to correct as many as possible, but if you discover errors while listening, please send corrections to info@arhoolie.org

Chris Strachwitz: Speaking to Octa Clark here. Could you give me your birthday again?

Octa Clark: My birthday is the last day of April.

Chris Strachwitz: That’s the 31st of April and what year were you born.

Octa Clark: 1904.

Chris Strachwitz: Did your daddy play accordion, too?

Octa Clark: Yeah. A little bit. All the family.

Chris Strachwitz: Your mother, too?

Octa Clark: No, not momma family, my daddy family. They all play. The lady, the man and everyone.

Chris Strachwitz: Mostly accordions? Also fiddles?

Octa Clark: Accordion. Yeah. And on my momma’s side, my aunt played the fiddle, played the guitar, and they accordion, too.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you know your grandfather, too? Did he play, too?

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: How do you think his style, was it a lot different from yours?

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah. A lot. A lot different. Well, I guess I don’t know how I can say that, because I believe they got to made the songs. They don’t hear no radio. They don’t hear no “graphophone”(gramophone), nothing. They got to just think about what they want to do and try to make a tune. I guess that’s the way they go. They had a lot of different songs. They called that, like I said, the polka, valse a deux temps, mazurka, and all that.

Chris Strachwitz: Back in those days, did they have a similar kind of accordion, always a one row?

Octa Clark: Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: Just like you play now.

Octa Clark: Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: It has always been that way.

Octa Clark: That was the only thing they had. The name of those accordions was Lester. They called them Lester Accordion.

Chris Strachwitz: Lester?

Octa Clark: The first accordion I played on, I had 9 years old. I begin it. My daddy bought it. It was a little black accordion and he bought it for 2 dollar and a half. Brand new! He brought it home.

Chris Strachwitz: They were that cheap back in those days?

Octa Clark: Yeah. I started playing that and soon I could I play almost everything I want. Just like that.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you learn mostly from your daddy?

Octa Clark: No, I learned more from the good musicians. The good ones. Musicians, you know.

Chris Strachwitz: Do you remember some of them?

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: Could you name me couple of them.

Octa Clark: Yes, I can name them. The one is, they call him Alfred Simone (?) and the other one is Dujean Simone (?) They’s two cousins, but they was good playing. Oui. Cousin with daddy. The other one was Frank Roy . That’s the one, I learned with him, too.

Michael Doucet: I never heard of them. They all came from around here? They came from Bayou Sauvage?

Octa Clark: Frank was raised by Acadiana, right close. He was raised there. One night I was play a dance at, they called that Tibby Simone, and I saw ol’ Frank come and but hear me by the band stand, and I beg him. I said, “Mr. Frank, how come you don’t come and play in my place a little while?” “Oh,” he said, “I don’t play. I don’t play.” I want to hear him, so I beg him. I said, “Come on, I like to hear you.” Well, he said, “All right.” He get on that and he played. I heard that waltz, that “old Musician Waltz.” That’s what I get him, with him.

Michael Doucet: Oh, wow.

Octa Clark: Yeah. I had 14 years old. I had it from that time. I keep going because I like it. And nobody keep on that dance. I didn’t hear nobody play that dance, so I played it.

Chris Strachwitz: Back in those days, did you play mostly house parties or was there dance halls already?

Octa Clark: Well, they had dance halls and they party. A lot of party.

Chris Strachwitz: This was like after the first war? Was this after World War I?

Octa Clark: Yeah. The first war.

Chris Strachwitz: When you started playing?

Octa Clark: Yeah. First war.

Chris Strachwitz: And they already had little dance halls.

Octa Clark: Yeah, they did. Not too close, but they had some.

Chris Strachwitz: What were most of the dance bands like? Just accordion and fiddle, or did they have rub board or guitar?

Octa Clark: They had tingaling.

Chris Strachwitz: A triangle.

Octa Clark: Fiddling and a guitar, that’s all.

Michael Doucet: Who was in your first band. When you played, did you play just alone?

Octa Clark: You know, the first band I had, I play a lot of times just accordion and guitar. That’s all. Sometime I had a fiddle. Sometime. I play all the dance like that.

Chris Strachwitz: Were there a lot of musicians all over the place?

Octa Clark: Oh, no. Not too much.

Speaker 4: Not too many.

Octa Clark: The young ones don’t learn it too much. The ones keep on that. When I heard them there about that time they’re passing the road about late at night about sundown in a buggy and they play that. I was stay right there and they pass on the other road over there. I sit down outside and I listen. I said, “Lord, Lord, never …….. do that that much.” And I be dogged. I come along, I keep on that, you know. When you want something, if you’re going to keep on, you get it.

Michael Doucet: Did you play a lot in those days? How did you get there? How did you? Did you play every day?

Octa Clark: For a while, almost. Almost. I work hard here. I work in the field. I go all day. At night I go play a party until 1:00 o’clock. Next morning, piocher(?) again. That come hard.

Chris Strachwitz: And most of the music you heard when you were growing up was French numbers like …

Octa Clark: All French.

Chris Strachwitz: What did you think when you first heard a record or a radio? Do you remember the time when the radio or the records come in? Did you think much about it?

Octa Clark: No, no. I don’t remember too much that. No.

Chris Strachwitz: You still just kept on listening to other people and played your own tunes?

Octa Clark: Yeah. I keep on. I told you what happen with me. I couldn’t go to bed at night and the day after that day, when I get up in the morning, I had a dance music. I can make a new dance. I went in to Maurice. They had a big bazaar there. The Black Eagle band was playing.

Chris Strachwitz: Oh, yeah. That brass band from New Orleans?

Octa Clark: I don’t know where they come from but they all niggers. And I went there, and I hear and you know I got a tune from them.

Michael Doucet: Do you remember which tune you got from them.

Octa Clark: I could play that again.

Michael Doucet: Which tune was it? Do you remember?

Octa Clark: I don’t remember the name, you know, but I can play that tune again.

Chris Strachwitz: Was it a two-step or a waltz?

Octa Clark: It’s two-step.

Chris Strachwitz: You didn’t record that for us yesterday, did you?

Octa Clark: Oh, no. No, I never record that.

Chris Strachwitz: Ah, I’d like to hear that one.

Octa Clark: Another time, I went to my Aunt, make a voyage(?) and they had a ‘graphophone’ there and they play a tune. Next day, I got it. I can play that tune. Long time I didn’t do it, but I can do it. That’s the way I learn it.

Chris Strachwitz: You just hear the tunes and then you put it on the accordion, huh?

Octa Clark: Yeah. And right after, I can do it. But the day after I hear it, I can hear that tune in my … All day long I can hear it. That’s when I catch it. It’s coming. That’s funny. I’m not like that now, because I believe I get old and I don’t remember that much.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you hear any other colored bands that you remember? You know, negro bands that you went to?

Octa Clark: Not too much, no. I catch a few, because the nigger wasn’t stay around here. If I heard them I catch it, you know. One time I was going in the road with the wagon and I had a young little nigger about 13 years old. He asked me for a ride. I said, “OK, come in.” So he got a little tune that he was singing and whistling, singing and whistling, and you know, I got it. (laughs)

Michael Doucet: What do you call that tune? Which one is that one?

Octa Clark: I call that “The Black Top Blues.”

Chris Strachwitz: Oh, The Black Top Blues . That’s a good song.

Octa Clark: The Black Top Blues. (laughs)

Chris Strachwitz: But by the time they started making records, you already knew a lot of tunes, I guess, and you didn’t …

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah.

Michael Doucet: When Joe Falcon did his records, you were already playing.

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah. I play with Joe Falcon lot of times. I play with Amédé Breaux.

Michael Doucet: How was Amédé Breaux? He was a good player.

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah. He was better than Joe to play, but Joe was a better singer. When I get to the dance and Amédé was playing, when he saw me, he said, “Come sing!” So what he do? He give me the accordion and he take the fiddle or the tingaling. ……… We stay good friends.

Chris Strachwitz: Where did they live? In Rayne?

Octa Clark: Well, they all down, I believe, in Rayne. Long I remember he live in Rayne.

Chris Strachwitz: The whole family?

Octa Clark: Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you hear Cléoma Breaux a lot when she use to sing?

Octa Clark: Who?

Chris Strachwitz: Cléoma Breaux, you know.

Octa Clark: Cléoma? Oh, yeah. Yeah. Oh, yeah. A lot of times.

Michael Doucet: Didn’t they have a lot of women singer doing this more when you got started?

Octa Clark: No. That’s the only one that sing at that time.

Michael Doucet: How did you and Hector get together?

Octa Clark: Well, Hector like to play the fiddle and Jesse Duhon the guitar. They had about 13 years old, and they come meet me. They want to learn. “Well,” I said, “If you want to learn, come on. We going to play.” So I play and they try, they try, they try, they try. When they know enough to bring it to the dance, I bring it over that with me and we start from there. Oh, they like that , and we make money.

Michael Doucet: How much money did you all make?

Octa Clark: I make 4 dollars at the dance, and they make each one 1 dollar. (laughs).

Chris Strachwitz: That was big money back in those days.

Octa Clark: (Laughs) You talk about money.

Michael Doucet: When was that? When did you all first get together? About what year? You and Hector?

Octa Clark: Well, you know Hector is 66 years old …

Chris Strachwitz: It was when he was 14 you said?

Octa Clark: … And he had about 13, 14 years.

Michael Doucet: 53 years ago, something like that? That would be in the ‘30’s.

Octa Clark: About that.

Chris Strachwitz: Early ‘30’s. And then for a while, he went off and played with the little group they had, the Dixie Ramblers, was it?

Octa Clark: Yes. You know what, I lost my dad first, so I stopped. I said I quit for a while, so he started get with the string band.

Chris Strachwitz: Oh, you quit playing for a while.

Octa Clark: Yeah, for a while. Then he come back again with me. After that, we don’t play too much, so somebody else come and get to play with them. That don’t have a good fiddler. I do it. I said, “I got a good one.” They said, “Yeah? Well get it.” So I get Hector, and we play from there. We play at the Lafayette and Mrs. Webb for 6 years straight. And they changed. The people that run the place change 3 times. Sometime I didn’t know which one is the boss. (laughs)

Chris Strachwitz: What was the name of that club?

Octa Clark: Mrs. Webb Lounge.

Chris Strachwitz: Mrs. Webb Lounge. That was in the early ‘50’s when …

Octa Clark: Down there in ’54.

Chris Strachwitz: Was that about the time that the accordion music come back pretty strong here?

Octa Clark: Oh, yes. We play on the Jamboree. At the Jamboree, we start at about 5:00 o’clock every Saturday afternoon. I play a little while and somebody else want to play. They play, so I play the dance after that.

Michael Doucet: Was that a radio program?

Octa Clark: Yeah. Yeah. For 6 years we had that on.

Chris Strachwitz: Oh, you were on the radio for 6 years. Remember the station’s name that broadcast that?

Octa Clark: KSIG in Crowley.

Chris Strachwitz: They would come and bring their microphones there and broadcast?

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: I imagine you had some good times at those.

Octa Clark: Oh, the dance hall was full all the time. At 5:00 o’clock to 1:00 o’clock. And when I go to collect at the boss, they take 4-5 dollar bills and they roll them and put them in my pocket. I say, “What’s that?” He said, “OK, OK.” I said nothing. That’s a tip he give me. Good money.

Chris Strachwitz: By that time, how much would you get for a night for …

Octa Clark: Oh, at that time, we don’t get too much. About 10 dollars a head. That’s all.

Chris Strachwitz: I guess beer was still pretty cheap back then.

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: What was the most enjoyable thing about playing dances. Is there anything special that you enjoy the most?

Octa Clark: Just you like that. That’s all. Like that. I make for all my life with that, you know. I not be interest to dance and all that. If I can play and see the people have a good time, that’s OK with me.

Michael Doucet: What is music to you? What does that mean to play French music and play accordion? What does that mean to you?

Octa Clark: What that mean to me? Well, it just mean like a pastime. When I got back to the fields sometime, I was tired. If I can play a little while, it get me up again. I’m that way.

Michael Doucet: What does take .. I know you’re one of the best if not the best because that’s just it, but what does it take to be a good Cajun musician?

Octa Clark: It takes the speed with your fingers, a good mind to keep on the tune, and learn something. When you learn it, keep it. And you can play different. You can play the same. I can do that. Somebody going to come and play one tune there that come out one different way. So, I going to come out and play the same tune and it going to come out different. You can make a tune a little pretty that use different notes, so that make a big difference what a man accordion. If you’re going to make it pretty, and you can make it, that’s the best way to make it. You can do that. That’s like you play a fiddle. Somebody can make a fiddle sound different with the same tune you’re going to play, …….

And somebody don’t know how come I don’t open my accordion. I don’t need that. You’ve got to study. No matter how, you need to play what you want to play. A lady asked me that at the…..party over there. And she said, “I don’t understand that. When I play, I don’t have enough. I bring it that way, I don’t have enough air.” Well, I said, “That’s something, lady, you got to learn. Like whistling. If you start a whistling something and you don’t stop, you’re going to miss air, too.”

You got to learn how you going take enough air to keep on with that. And that’s how accordion is made. You’ve got to run just to keep the air the way you want it.

Michael Doucet: Who was the best Cajun musician you ever heard? Who, to you, was the best?

Octa Clark: Well, they all good. I believe they all good.

Michael Doucet: Which one struck you as someone that was playing it right?

Octa Clark: Well, I believe the old one, that’s what I call that Frank Roy, exactly. Oh, yeah.

Michael Doucet: Because, I know you play the rhythm the best.

Octa Clark: And you take Joe Falcon, was very good too. And Amédé Breaux was very good too. Amédé Breaux was good too. He was first a singer and he was good, too. A lot of people were good, but some like Aldus Roger, you going to hear him. He’s a good playing, but an old musician told me. He said, “Clark, nobody can beat you for dance.” I said, “You believe so?” He said, “Yes. “

He said, “When you dance, you don’t miss your step. Aldus cut, and you got to change you step.” I said, “I didn’t know that.” He said, “Yeah.” And we played in the four over there. Austin told me, he said, “ You know the different you have when you play and Aldus play? “ I said, “No, I don’t know. “ He said, “Well, on my register, 100 dollar difference.” I said, “What?!” “Hundred dollar.” I said, “Aldus had 100 dollar more than me?” He said, “No, you got it. “ And I said, “Sure enough?”

He live here. Go talk with him, he’ll tell you that.

Michael Doucet: That’s Austin. Austin Brussell (?).

Octa Clark: He got the Four Rose there. He run the Four Rose for a long time. And when Four Rose was down, nobody could make that Four Rose start again. He try. He try making people come there. Nobody would come. They come and see me.

He said, “I can’t give you much because I don’t have no much people. Now if you going to give me a chance. If you bring people here,” he said, “Don’t worry about it.” He said, “You going to make more now. I going to make some, too.” “Well,” I said, “I’ll give you a chance.” So the first dance, I was playing the Jamboree over there, I tell that to the people. I was going to the Four Rose.

Michael Doucet: On the radio?

Octa Clark: On the radio, yes. We drove back to the Four Rose. Over there, that man get mad. Over there, these people left and they follow me. So the second dance I play at the Four Rose, I told Austin. I said, “Look, you better get more table, more chair.” He said, “What?” I said it was almost full there tonight and the next dance, it was full. He put eight table more and the chair with them. The next dance, we got it full, full, full, and we keep that about three years like that.

Chris Strachwitz: You’ve got a nice rhythm, so they really like….

Octa Clark: I believe that’s what. He said that’s a good music for dance. That’s what they told me. Good music for dance. And I had here Alvin Soule (?). You know Alvin Soule?

Michael Doucet: Yeah.

Octa Clark: He was playing with me. One night, this was full, full, full, and they still at the door to come in. He said, “God dog. They look like we giving something here, the way they come in.” “Well,” he said, “One thing we’re giving, we’re giving them good music.” I said, “You’re right.” (laughs).

Chris Strachwitz: That’s a great….

Michael Doucet: Well, the people are going to listen to your album for the first time, and they’re going to say, “How can I learn this?” What would you tell them, when they hear your album for the first time? What can you tell them? What would you say when somebody come here with your album and say, “Oh, Mr. Octa, I have you album. I think it’s the best music I’ve ever heard. What is it? How do I learn? What is it?”

Octa Clark: Well, I let them say what they want to say. A lot have told me. Long time ago, you’re supposed to make something. I don’t know how many people ask me when they come up. Let me go and let me know. I want some. I want some. And they still they tell me that. And they never come on. Look like I was a liar.

Chris Strachwitz: It’s going to come out now. He says, “Come on, I’ll try it fast. “

Chris Strachwitz: But really the French music has always been mainly for dancing, isn’t it?

Octa Clark: Yes. Yeah. It’s for dancing.

Chris Strachwitz: For dancing because … but I guess there were people who sang in the house. Did you just ever whistle tunes when you work?

Octa Clark: No, I don’t whistle too much or sing too much, but I got in my mind. I got it inside. Nobody can catch it. (laughs) I believe that’s natural. It got to be, because a lot of people try. A lot of people come here.

You take like Bessyl (?). Bessyl was … I show Bessyl all what I can because I like Bessyl. He’s a good boy for me and last time he came here, with his accordion and fiddle, and he said, “Let’s play a few tunes. “ He told me, he said, “I want you to show me how to play Bosco Stomp.” Well, I say, “You can play it.” He said, “Yes, I show you the way I play them.” So, the way he playing, he can do it different and easy. So I said, “Bessyl, it’s not that way. I going to show you how to play.” So I take my accordion and I show him how to turn it. So he turn it. He said, “Well, I try to keep that in my head.” He said, “If I forgot about it, I come with a tape recorder and I’m going to record that. “

And the Bosco Stomp is not hard to turn and you don’t imagine how many people was learn to play and they come here to learn that. They can play but they can’t turn it. They can’t turn. Well, I said, “I’ll be doggone.” I show them how to do it, young people. I like to show that to young people. I’m getting old. I guess somebody going to try to take my place sometime. I like to hear that.

Michael Doucet: Me, too. (laughs)

Octa Clark: And I show them. They was glad to know that. I don’t know how many thank you. If they want to buy an accordion, they going to come see me to check this accordion, how it look. They believe I, maybe they believe I know more than I know. (laughs).

Chris Strachwitz: You said in the old days when you started, or when you heard daddy and those people, did they have names to all the songs? Or not?

Octa Clark: Yeah. They had names, but I don’t remember exactly. They called that one, “?.” They called one, “Lancier.”

Michael Doucet: Oh, oui. Le Lancier.

Octa Clark: Oh, ….., something like that. But I don’t remember exactly the tune.

Michael Doucet: Those are old songs. Le Lancier.

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah. I don’t know how that go, but I believe that they put two lines. And one get, come and make two-three run and get back, and the other one go. It’s one that turn. I guess that’s the way they go, but I’m not sure.

Michael Doucet: Do they sing a lot in the old days more?

Octa Clark: No, they dance. The accordion play that.

Michael Doucet: Like when you sing a song where does that song come from? Do you sing a story? Or are do you thinking about a certain thing? Each story is different. Where does that come from… the story of the song? L’histoire de chanson?

Octa Clark: Moi j’connais pas.

(I don’t know)

Michael Doucet: Mais, quand tu chantes ça,quand tu chantes “La Valse à Mèche”.

(But, when you sing that, when you sing “La Valse A Meche”)

Octa Clark: Oh ouais, c’est justement quelqu’un qu’a fait ça comme ça parce que il voulait faire quelque chose et il a jonglé faire une valse des mèches.

(Oh yeah, it was just someone who did it like that because he wanted to do something and he thought about making a waltz about the marshes.)

Michael Doucet: Il a jonglé , c’est ça?

(He thought about it, right?)

Octa Clark: Il a jonglé ça ça.

(He thought about it.)

Michael Doucet: Et toi aussi? Tu as jamais fait des paroles? Mais, t’as fait des paroles de toi même?

(And you too? You ever made up lyrics? Well, you made up lyrics yourself?)

Octa Clark: Well, ouais, y’a pas rien d’écrit la dessus. Tu connais?

(Well, yeah, there’s nothing written of it. You know?)

Michael Doucet: Ouais, ouais.

(Yeah, yeah.)

Octa Clark: ….tu prends les chansons, il y a tas de chanson qu’est écrit. All the words. Dans ce temps là, y’a pas de chansons qu’étaient écrites. Fallait t(u)i fais ça, toi tu écrit, toi tu voulais.

(…. you take the songs, there are lots of songs that are written. All the words. At that time, there were no songs that were written. You had to do this, you’d write, if you wanted.)

Michael Doucet: Chapeau!

(Hat!)

Octa Clark: And uh, the old folk call one dance “cotillion“. Et quoi tu crois c’était une cotillion? “Saute Crapaud“!

(And uh, the old folk call one dance “cotillion”. And what do you think is a cotillion? “Jump, Frog”!

Michael Doucet: C’est ça une “cotillion”?

(That’s a “cotillion”?)

Octa Clark: That’s what they call “cotillion“, “Saute Crapaud”

Michael Doucet: Just one tune they call “cotillion“?

Octa Clark: Yeah.

Michael Doucet: You know that?

Chris Strachwitz: Yeah.

Octa Clark: You heard about that “Cotillion, eh?

Chris Strachwitz: No, I’ve heard that tune, “Saute Crapaud.” How would they do that cotillion?

Octa Clark: I don’t know how come they called that the Cotillion and “Saute Crapaud,” I don’t know. But I heard that from an old man. He was playing a little bit. I don’t know where he went, too. Where. And they told him, “Play “Cotillion.” He said, “I don’t know.” “You don’t know play “Cotillion?” “No, I don’t know.” While ago, he started playing “Saute Crapaud.” They said, “That “Cotillion!” (laughs) That’s what I mean that the old folks, “Cotillion,” they called “Saute Crapaud,” too.

Chris Strachwitz: But in those days, people didn’t know as many different numbers as they do now, did they?

Octa Clark: Oh, no.

Chris Strachwitz: They just played a few all night long?

Octa Clark: Yeah. They play almost the same ones all the time. When they catch a new one, sometimes they come up with that.

Chris Strachwitz: The people didn’t hear as much music like today……

Octa Clark: Oh, no.

Chris Strachwitz: They were satisfied with just a few. Did you play them a lot longer sometimes? Did you always play them about 3 minutes long, or did you in the old days play them longer. Like, let’s take a waltz or whatever. How long would you sometimes play them at a dance?

Octa Clark: You got to watch how the people get along in that. If you play your dance too long, the old folks in there, they hard to make it, so you got to find out. Don’t play too long because they were satisfy. They dance enough. The next dance, they can dance with somebody else. That’s why………. Walter Mouton. They complain that he dance too long. I told Walter Mouton. We good friend. I said, “Walter, I don’t want to tell you what to do, but I know if you heard something about for me, I be glad you told me.” And I said, “If you want, I told you.” Well, he said, “I’m glad. ” Well, I said, “Don’t play your dance too long. Play it a little short.” He forgot about, I guess, and he keep on play too long.

Chris Strachwitz: But you think back when you started, you played them about the same length as you do now?

Octa Clark: Yeah. About the same.

Chris Strachwitz: Oh, is that right? I thought maybe the records made it different. That a record was only 3 minutes long, but you don’t think that made that much difference.

Octa Clark: No. I don’t believe.

Unknown: Did they always wait about 5 or 6 or 7 minutes between songs? Between dances, so people could have a drink.

Octa Clark: Yeah. Yeah. That’s why I watch……….When I went to the dance hall, well I start playing. And the dance that don’t drink, all of them in the ring, I never play back again.

Unknown: That eliminates a lot of tunes.

Octa Clark: Nobody back then had to tell you that. You know they don’t like it.

Chris Strachwitz: This is obviously how certain dances get lost, like maybe the mazurka. If you found out they didn’t react to it, you just forgot about it.

Octa Clark: Yeah.

Michael Doucet: The two-step was an early dance, did you remember? That was there. That was earlier than the two-step? Or that came about later?

Octa Clark: I believe waltz…..

Michael Doucet: It was just simpler, because you spoke before, when you turn it. What’s a turn, when you make a song, what’s a turn.

Unknown: Second part?

Michael Doucet: How do you make a turn. You change it a little bit.

Octa Clark: Well, it might be changed a little bit, but it changes the way you dance, you know. The style. The style, the way they dance.

Michael Doucet: That’s right. I forget about that.

Octa Clark: You remember … you was too young. I remember that. They had a dance they called it one-step and they make a long step like that. Then they stopped. Put the brakes like that. The lady come on that knee. (laughs)

Michael Doucet: Oh. That’s what the one-step was?

Octa Clark: The one-step. Yeah.

Michael Doucet: In other words, you danced like this. You go like this?

Octa Clark: A fast-fast and a long step, and when you beside, you stop. Then you start again. And one night, I was a good little friend. I go out with that little girl. She had a long dress. My neighbor, he told me, he said, “What that girl had a long dress.” I said, “Yeah. Yeah.” He said, “If you want to dance with her back her fast and stop, and bust that dress, I’ll give you two bits.” Well, I said, “OK.” So I went and started dance. (laughs) When I stopped like that, my big long legs, I just stopped and she climbed on that…… busted her dress. So, we stopped dancing. She went to the restroom over there and fix it, and I go get my two bits. (laughs).

Michael Doucet: To play a one-step, how is the one-step different than a two-step, though, to play.

Octa Clark: Well, the one-step and the two-step is almost the same thing. It’s just danced different. That’s all.

Unknown: Do they have an extra beat in between the parts for that stop?

Octa Clark: No. About the same thing.

Michael Doucet: That’s great about the dress.

Chris Strachwitz: Yeah.

Michael Doucet: You must have some other stories like that.

Chris Strachwitz: How do people dance?

Chris Strachwitz: Did they always dance the waltz like they do now, or did they used to dance it with more like in Europe? I don’t know if I can explain it.

Unknown: Turn.

Chris Strachwitz: Yeah. Turn more. Did they ever do that more?

Octa Clark: No. No. They don’t turn that much.

Chris Strachwitz: They never did.

Octa Clark: A man, they turn when they get to the corner, then they keep on going … I saw there on the TV, they almost turn all the time.

Chris Strachwitz: When they started, I think, the waltz in Austria at the turn of the century, they had really elaborate turns all through it.

Octa Clark: Yeah. I believe that’s the way they start, and they change it a little bit.

Chris Strachwitz: Was a polka considered a kind of a nasty dance when it first come out? Or you don’t remember it.

Octa Clark: The polka is the still the same]. They dance that the same thing when I first know that they dance now. The same thing.

Michael Doucet: (French )

Octa Clark: No.

Michael Doucet: (French)

Octa Clark: No. (French) (whistles) Don’t go smoking in the dance hall. Oh, no. And when you finish dance, let your lady go sit around and get away from that. Oh, yeah. They were strict. You can’t get a girl and go to the dance. They put you out right now. You got to bring with his mama. The mama was there all the time with the girl.

Unknown: She brought her.

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah.

Unknown: Then the men came by themselves.

Octa Clark: (laughs) All of my friends. He make me laugh. Yeah. He said, when I walk with that little girl. He said, finally, I walk. I just grab it across the bottom like that. She said Ungh! She left me on the side, pushed me over, and when I come back to catch it, I can’t catch, I can’t catch it. He said, I got to grab just the skin, just the jaws of the hound. (laughs) Said, that’s all he can touch. The skin of that ….. and that’s all I can touch. (laughs)

Michael Doucet: That’s not good. Did you meet your wife at a dance.

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Michael Doucet: She was a good dancer?

Octa Clark: Oh. Too good.

(Everyone laughs)

Unknown: Steal her heart away.

Speaker 4: (French)

Chris Strachwitz: Well, I think we’ve got … anything more you want to say?

Octa Clark: I’m through with the truth.

Unknown: Get started on the lie.

Octa Clark: (laughs)

Chris Strachwitz: They’ve got some stories.

Octa Clark: Aw, shucks.

Chris Strachwitz: I imagine you had some good times playing these dances.

Octa Clark: Oh, yeah. All the time. I had all the whiskey and moonshine I want to drink. Don’t cost me nothing. Had a lot of friends as I wanted. Each one wanted me to go play at their house. Come play tonight. I’ll make you a big gumbo or something like that. So we get together and we went over there. I’ve had a good time.