Chris Strachwitz on Houston Record Labels

Jazz Report Vol. 2 No. 8. In 1962 Chris Strachwitz was writing a blues column for Jazz Report magazine. Here is part two of three articles about his travels in the south.

Key to the Highway

Number Two In a Series by Chris Strachwitz

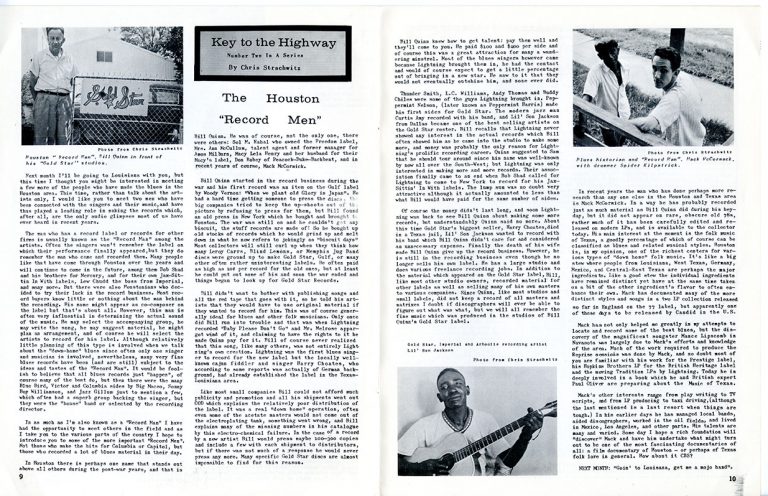

The Houston “Record Men”

Next month I’ll be going to Louisiana with you, but this time I thought you might be interested in meeting a few more of the people who have made the blues in the Houston area. This time, rather than talk about the artists only, I would like you to meet two men who have been connected with the singers and their music, and have thus played a leading role in making the records which, after all, are the only audio glimpses most of us have ever heard in recent years.

The man who has a record label or records for other firms is usually known as the “Record Man” among the artists. Often the singers won’t remember the label on which their performance finally appeared, but they do remember the man who came and recorded them. Many people like that have come through Houston over the years and will continue to come in the future, among them Bob Shad and his brothers for Mercury, and for their own Jax-Sittin In With labels, Lew Chudd the boss from Imperial, and many more. But there were also Houstonians who decided to try their luck in the record business. Most record buyers know little or nothing about the man behind the recording. His name might appear as co-composer on the label but that’s about all. However, this man is often very influential in determining the actual sound of the music. He may select the accompanying group, he may write the song, he may suggest material, he might plan an arrangement, and of course he will select the artists to record for his label. Although relatively little planning of this type is involved when we talk about the “down-home” blues since often only one singer and musician is involved, nevertheless, many very fine blues records have been (and are still) subject to the ideas and tastes of the “Record Man.” It would be foolish to believe that all blues records just “happen”, of course many of the best do, but then there were the many Blue Bird, Victor and Columbia sides by Big Maceo, Sonny Boy Williamson, and Jazz Gillum just to mention a few, which often had a superb group backing the singer, but they were the “house” band or selected by the recording director.

In as much as I’m also known as a “Record Man” I have had the opportunity to meet others in the field and as I take you to the various parts of the country I hope to introduce you to some of the more important “Record Men”. Not those who make the hits for Columbia or Capitol, but those who recorded a lot of blues material in their day.

In Houston there is perhaps one name that stands out above all others during the post-war years, and that is Bill Quinn. He was of course, not the only one, there were others: Sol M. Kahal who owned the Freedom label, Mrs. Ann McCullum, talent agent and former manager for Amos Milburn, Macy Lela Henry and her husband for their Macy’s label, Don Robey of Peacock-Duke-Backbeat, and in recent years of course, Mack McCormick.

Bill Quinn started in the record business during the war and his first record was an item on the Gulf label by Woody Vernon: “When we plant old Glory in Japan.” He had a hard time getting someone to press the discs, the big companies tried to keep the up-shoots out of the picture by refusing to press for them, but Bill found an old press in New York which he bought and brought to Houston. The war was still on and he couldn’t get any biscuit, the stuff records are made of! So he bought up old stocks of records which he would grind up and melt down in what he now refers to jokingly as “biscuit days.” Most collectors will still curl up when they think how many Leroy Carrs, Blind Lemons, or Memphis Jug Band discs were ground up to make Gold Star, Gulf, or many other often rather uninteresting labels. He often paid as high as 10₵ per record for the old ones, but at least he could put out some of his and soon the war ended and things began to look up for Gold Star Records.

Bill didn’t want to bother with publishing songs and all the red tape that goes with it, so he told his artists that they would have to use original material if they wanted to record for him. This was of course generally ideal for blues and other folk musicians. Only once did Bill run into trouble and that was when Lightning recorded “Baby Please Don’t Go” and Mr. Melrose apparently got wind of it, and claiming to have the rights to it he made Quinn pay for it. Bill of course never realized that this song, like many others, was not entirely Lightning’s own creation. Lightning was the first blues singer to record for the new label but the locally well-known cajun fiddler and singer Harry Choates, who according to some reports was actually of German background, had already established the label in the Texas-Louisiana area.

Like most small companies Bill could not afford much publicity and promotion and all his shipments went out COD which explains the relatively poor distribution of the label. It was a real “down home” operation, often even some of the acetate masters would not come out of the electroplating tank, something went wrong, and Bill explains many of the missing numbers in his catalogue by this electro-chemical failure. In the case of a record by a new artist Bill would press maybe 100-300 copies and include a few with each shipment to distributors, but if there was not such of a response he would never press any more. Many specific Gold Star discs are almost impossible to find for this reason.

Bill Quinn knew how to get talent: pay them well and they’ll come to you. He paid $100 and $200 per side and of course this was a great attraction for many a wandering minstrel. Most of the blues singers however came because Lightning brought them in, he had the contact and would of course expect to get a little percentage out of bringing in a new star. He saw to it that they would not eventually outshine him, and none ever did.

Thunder Smith, L.C. Williams, Andy Thomas and Buddy Chiles were some of the guys Lightning brought in. Peppermint Nelson (later known as Peppermint Harris) made his first sides for Gold Star. The modern jazz man Curtis Amy recorded with his band, and Lil’ Son Jackson from Dallas became one of the best selling artists on the Gold Star roster. Bill recalls that Lightning never showed any interest in the actual records which Bill often showed him as he came into the studio to make some more, and money was probably the only reason for Lightning’s prolific recording career. Quinn suggested to Sam that he should tour around since his name was well-known by now all over the South-West; but Lightning was only interested in making more and more records. Their association finally came to an end when Bob Shad called for Lightning to come to New York to record for his Jax-Sittin’ In With labels. The lump sum was no doubt very attractive although it actually amounted to less than what Bill would have paid for the same number of sides.

Of course the money didn’t last long, and soon Lightning was back to see Bill Quinn about making some more records, but understandably Quinn said no more. About this time Gold Star’s biggest seller, Harry Choates, died in a Texas jail, Lil’ Son Jackson wanted to record with his band which Bill Quinn didn’t care for and considered an unnecessary expense. Finally the death of his wife made Bill Quinn give up the record business. However, he is still in the recording business even though he no longer sells his own label. He has a large studio and does various freelance recording jobs. In addition to the material which appeared on the Gold Star label, Bill, like most other studio owners, recorded material for other labels as well as selling many of his own masters to various companies. Since Quinn, like most studios and small labels, did not keep a record of all masters and matrixes I doubt if discographers will ever be able to figure out what was what, but we will all remember the fine music which was produced in the studios of Bill Quinn’s Gold Star label.

In recent years the man who has done perhaps more research than anyone else in the Houston and Texas area is Mack McCormick. In a way he has probably recorded just as much material as Bill Quinn did during his hey-day, but it did not appear on rare, obscure old 78s, rather much of it has been carefully edited and released on modern LPs, and is available to the collector today. His main interest at the moment is the folk music of Texas, a goodly percentage of which of course can be classified as blues and related musical styles. Houston is, in my opinion, one of the richest centers for various types of “down home” folk music. It’s like a big stew where people from Louisiana, West Texas, Germany, Mexico, and Central-East Texas are perhaps the major ingredients. Like a good stew the individual ingredients have remained distinct yet have at the same time taken on a bit of the other ingredients’ flavor to often enhance their own. Mack has documented many of the more distinct styles and songs in a two LP collection released so for in England on the 77 label, but apparently one of these days to be released by Candid in the U.S.

Mack has not only helped me greatly in my attempts to locate and record some of the best blues, but the discovery of the magnificent songster Mance Lipscomb in Navasota was largely due to Mack’s efforts and knowledge of the area. Much of the work required to produce the Reprise sessions was done by Mack, and no doubt most of you are familiar with his work for the Prestige label, his Hopkins Brothers LP for the British Heritage label and the moving Tradition LPs by Lightning. Today he is deeply involved in a book which he and British expert Paul Oliver are preparing about the Music of Texas.

Mack’s other interests range from play writing to TV scripts, and from LP producing to taxi driving, (although the last mentioned is a last resort when things are tough). In his earlier days he has managed local bands, aided discographers, worked in the oil fields, and lived in Mexico, Los Angeles, and other parts. His talents are many and varied. Some day I hope a rich foundation will “discover” Mack and have him undertake what might turn out to be one of the most fascinating documentaries of all: a film documentary of Houston — or perhaps of Texas folk lore in general. How about it CBS?

NEXT MONTH: “Goin’ to Louisiana, get me a mojo hand”.

Chris Strachwitz – 1962