Moses Asch Interview

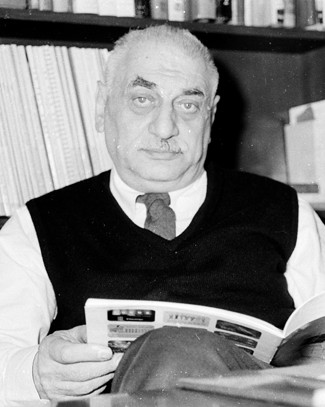

“Harry Smith is a nut, right? He knows every date, he knows every place, he knows everything.” – Moses Asch (1905 – 1986), Founder of Asch Records, Disc Records, & Folkways Records

- The Robert Stone Sacred Steel Archive: Elton Noble Interview 00:00

Interviewee: Moses Asch

Interviewer: Chris Strachwitz

Date: 1981

Location:

Language: English

This interview was recorded on a casette by Chris Strachwitz in his car. The original cassette has not yet been found. This is an edited version Mr. Strachwitz played on his radio show “Folk Music in America” which was broadcast in 1982 on KPFA-FM in Berkeley, CA. All rights to the interview are reserved by the Arhoolie Foundation. Please do not use anything from this website without permission. info@arhoolie.org

To learn more about Moses Asch and Folkways Records (now Smithsonian Folkways), visit their website

See below photo gallery for a transcript of the interview

Moses Asch Interview Transcript:

A Note About the Transcriptions: In order to expedite the process of putting these interviews online, we are using a transcription service. Due to the challenges of transcribing speech – especially when it contains regional accents and refers to regional places and names – some of these interview transcriptions may contain errors. We have tried to correct as many as possible, but if you discover errors while listening, please send corrections to info@arhoolie.org.

Moses Asch: 1939 right? When I issued my first commercial recording. I sold those to the stores that I serviced in the under….]. I still was operating some of the equipment sales I built the amplifiers …. Especially the broadcasting equipment for loud speaker systems. This all made a turn … I also at that time was recording for the United States government, the governments in exile. Most of the heads of state of the governments that the Nazis ran over came to the United States, and the federal government sponsored their broadcasts back to their homeland to keep the spirits up of the people going. Everything’s gonna be all right. The government was not set up in the recording area, but I had my equipment and I was right there by the station so all these governments in exile were using my facilities until the government got officially and then they created the broadcasting that they did from Boston under government sponsorship.

Chris Strachwitz: This is actually before the Voice of America was officially established?

Moses Asch: That’s right. America we daren’t in those days become in any way involved officially with the governments in exile because we were still playing footsy with the Germans even though officially Mr. Roosevelt said, “We’re for the Allies,” they helped England and all that, but they still didn’t want to create a situation where the Germans would say this is an anti-war act. We didn’t get into the war until the Japanese bombed us in Pearl Harbor, right? Although the Germans did worse things than that, but they didn’t dare touch that part of that. It may have been oil interests, whatever.

Chris Strachwitz: OK.

Moses Asch: Then in 1939, the war is declared in Europe. In New York City we have the World’s Fair and the Russians for the first time in the history since communism had an exhibit in the World’s Fair. They were welcome for the first time. There was a firm that issued recordings from the Soviet Union that they got from the official sources. The Red Army Chorus and all that. Comes the war, comes the war, right, the Russians pull out of the World’s Fair. They had to pull everything back to Russia, so the firm that issued the recordings of Soviet material couldn’t get anymore. Just at that time, the Germans were more or less blocking with the Japanese the import of shellac which came from the east. There was a shortage of shellac in the United States and me starting originally with a small firm couldn’t get any shellac at all. Those that were in business before could get allocation 20% or 40% of the amount of shellac that they used the year before.

So Stinson who imported the Russians and pressed them here had shellac allotment and I had none. I met these people because I used to go to the Soviet movies and I met the people and they always had a stand there and they carried a few of my records, Ukrainian, whatever, so I got to know them. Here they tell me they can’t get any production because they don’t know what to put on a record. Here I have all of this stuff and I don’t have no shellac, so I made an agreement with them during the war that Stinson would give me the allotment, it would still be my record, I would still pay and it would still be Asch, but they would use their facilities for selling them and thus make money enough to keep going until the war ended. That’s how I operated until 1941. Then we entered the war. Then the war ended in ’45 and I was then through with Stinson.

Chris Strachwitz: You were sort of in partnership with him, or just …

Moses Asch: In partnership and relationship, too. Issuing records and I paid for the artists for they paid for the production because they had the allotment. I decided now’s the time to quit, the war’s over and I didn’t want to be associated with them by name because everybody knew the Asch name. I created a Disc company in ’47. The first thing that happened in the Disc company was that Norman Grants, I don’t know whether you know him or not, came to me. He was doing in the west coast during the war before concerts, just concerts for the troops. That was the jazz of the philharmonic. That’s what the place was called. He had all this wonderful jazz stuff, but he had no production and he had no way of reaching the public. He heard from people that I was a legitimate guy and I was able to produce and so forth and we made a partnership and so I issued the jazz of the philharmonic and the great artists like Oscar Pettiford and others.

Chris Strachwitz: The first Nat Cole come out …

Moses Asch: Nat Cole. Nat Cole caused a whole trouble because Nat Cole demanded 10 thousand dollars for the recording and Norman said that was my responsibility because I was issuing the records and I couldn’t afford it, so I went bankrupt at 300,000 dollars in ’47.

Chris Strachwitz: Oh really?

Moses Asch: Yeah, but the bankruptcy was in such a fashion that I lost my metal masters because the pressing plant also did the plating. I owed money to the plater and the pressing plant and whatever, and I didn’t have it because I had to pay this large amount to the jazz guys. They grabbed my masters. They happened to be in New Jersey, and I’m in New York and you can’t sue them. The law in New Jersey permits them to grab property to sell it to get their money back. All I had left was my test pressing. Eventually the pressing plant and the plating plant sold the masters to, the firm was Pickwick but it was a different name them.

Chris Strachwitz: Didn’t Stinson issue the master of those?

Moses Asch: Then Stinson when I broke up grabbed some masters and they had another for me to break up; I gave him rights to some masters about five of them. Afterwards what they was they copied all my records and they issued without permission, my recordings. Again, they were in California it was in New York, you can’t sue this way. It didn’t bother me. Then in ’47 I started Folkways. The gal that was then the person that worked with me like Marilyn now was able to buy from the Marshall for a thousand dollars all my assets; recording equipment, everything.

Chris Strachwitz: Who was this? This woman?

Moses Asch: What?

Chris Strachwitz: Who was this?

Moses Asch: The gal was Marian Distler and she was with me until ’57 when she died. She was the contact with Woody Guthrie and all my artists. She was the one that did all the business with them. In ’47 I created Folkways and the bank loaned me 3,000 dollars on the basis that I shown that I was able to operated and people wanted my records and so forth and that started me off.

Chris Strachwitz: By that time you started issuing the LPs, didn’t you? Or was that a few years later?

Moses Asch: No, LPs didn’t start till ’52, ’53. The first LPs. How I got into the LP business is very interesting. Sam Goody and I became very good friends very early, in about 1938-39. He had a secondhand record shop on Cortlandt Street. Cortlandt Street was the street which everybody from Wall Street had to go down in order to get the ferry to Jersey. That was a very good location. Lawyers and businessmen and whatever, they had to pass his store. He immediately saw what I was issuing had sale-ability to these middle class Jersey-ites. He immediately bought all of my records for this shop. Well, he grew so big that in a few years he opened up a very big store on 9th Avenue in New York. Then he had a general manager, Abner Levin who knew classical music. Anybody that wanted classical records would come to him and ask him for his opinion. He was the expert.

Abner Levin went to Sam and said, “Look, Asch has a catalog that we can sell on the LPs.” That was the time that RCA had a 33 and a third and Columbia had the LPs. Sam Goody went with Columbia LPs instead of with RCA 33 and a third. He was one of the first that broke that …

Chris Strachwitz: You mean RCA’s 45?

Moses Asch: Forty-five, I’m sorry. Yeah, 45. Columbia had the 33.

Chris Strachwitz: That’s right. That was a decision finally that made the long play records.

Moses Asch: Sam Goody told me through Abner, he’ll buy 100 each of all my catalog on LP because nobody was making LPs. Everybody was worried that 45 would take it, and Columbia didn’t have a big catalog yet on LPs. Here Abner said, “Hey this is the type of record that would fit to the customer that we want in our store, upper middle class.” He ordered 100 each. Immediately I came into the LP business.

Chris Strachwitz: What were the first ones you issued on LP?

Moses Asch: I think the first thing he ordered was James Joyce reading his poetry. Mostly was spoken word. At that time I issued out the jazz 11 record series, not folk music because those people still weren’t sure whether they would buy LP on folk. The jazz enthusiasts were interested. Yeah, and the spoken word.

Chris Strachwitz: How did you get into the folk music sort of, with Pete Seeger Leadbelly.

Moses Asch: The folk music was early, very early. My father, you know, was the author Sholem Asch, I don’t know whether you know who wrote famous books on Christ and so forth. When he came to this country from Europe after World War I, he became a lecturer outside of him being a worldwide correspondent and writer and whatever. As a lecturer, he went to mostly where Jewish communities were in towns like Toronto, like Vancouver; out in the west in Colorado and in other places. Wherever he went he sent me or brought back the local … they had this kind of a magazine about local heroes. Because in the west, the whole culture is based upon the hero and the bad man and all that. In each one of these magazines there was the lyrics of the folk hero, and what he did whether he was a murdered or he was a lover, or there was an explosion or whatever.

I became, very early after World War I exposed to the American folk idiom. Since my background through him is literature, I was interested in the lyrics and what they had to say and the stories they had to say. Then in the 1920s I went to Europe to study engineering in Germany because they had the start the inflation. With 300 single dollar bills I was able to eat and to pay for my semesters and pay for my lodging and pay for everything at a dollar a day because the mark devaluated every day. When I got there it was 100 marks for the dollar. When I left four years later it was 1 billion marks for the dollar.

Chris Strachwitz: In the late ’20s was this?

Moses Asch: I left in ’26. While there I was a student in Germany. This was on the Rhineland where in the Hauptschule …. Technischule… I wanted to be an engineer, the students from all over Europe and South America and that came there. What they did was, they got together the students, I was the lone American. They sang songs and they always laughed at me and sang only Indians ……….you have no folk songs. When I got back to the States, well before that I went on a vacation to Paris. They had a home there, with my folks. I came on a …, do you the …….. in Paris along the Seine. They have books, bookstores, right? I came across a book. I still own it. It was written by Alan Lomax’s father, John Lomax. He was a newspaper man in Texas who gathered all the song lyrics from all the farmers and everywhere and he put them into a book. Theodore Roosevelt, the president at the time of the writing of the book wrote an introduction to this book which said “This is the true American culture. This is the basis of American literature.”

That impressed me tremendously. Here were all the lyrics of the cowboy ballads, of the vagabonds, of all the bums and everything else I found in Paris. I had a source of what American folk music was at a very young age. When I came back home and between the books, my father sent me these pamphlets, and this book, I was able to gather together American folk things. Always from the literature.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you ever sing any of them yourself?

Moses Asch: Well, we always sang the “You’re My Sunshine,” or one of the cowboy ballads, but I’m not a musician at all. They spoiled me that in school.

Chris Strachwitz: But you tried a little bit…

Moses Asch: But meanwhile, of course, it comes to you … Anyway, I was here exposed to all this. When the war broke out, they needed shellac. World War II, right? At that time Victor, Columbia, and Decker sold the stores on packaged deals. You wanted to be an RCA dealer? You had to take everything RCA issued. The first issue of anything. You could only sell Classic, Beethoven, whatever, you still hadda take the cowboy and the blues and that. No matter what store you were. That maintained your license with the company. Same thing with Columbia, same thing with Decca, although Decca later broke that up by issuing very cheap records because the Depression started at that time. However, the war broke out and they needed shellac, so all these stores took from the seller all these black label records, all this wonderful folk material they had, and they sold them three for a dollar, 20 cents a piece, anything so they didn’t have to return it to the government for shellac schlag

I bought at that time about 500 of the most wonderful American folk songs on record. Mike Seeger bought from my collection and also from Harry Smith. Harry Smith is a nut, right? He knows every date, he knows every place, he knows everything. Here in California at that time he was, he’s a small fella, hunchbacked a little bit, who was able to go in the tail of a plane when they build the plane. They need the small guys to do that. They earned a fortune, something like $100 an hour or something. He took all this money and he bought all those black label records out from here. I bought quite a few from the east coast which I still have. Some of them we’ve donated to the library and so forth. That’s where Mike Seeger got some of his collections from me. There I was exposed to quite a bit, then when I heard this stuff and I associated it with the lyrics of the books and so forth I knew what the tune should be and I knew everything. That’s how I got into it.

Chris Strachwitz: I guess in New York City you didn’t really get to hear much of the music that came from the other parts of the United States?

Moses Asch: Not at all, only through records. They were called hillbillies because nobody wanted to bother with them. I had in my lifetime many guidance. First I had a guidance when I first issued my recordings. I was recording Einstein for the … to the countries, the occupied countries. He was very much interested that they shouldn’t lose hope, and they should understand that they’re going through a trial, but that really they should live through it.

Chris Strachwitz: This was during World War One?

Moses Asch: World War Two.

Chris Strachwitz: World War Two. He would come to your studio?

Moses Asch: No, I would go to Princeton. He was an old man. I would go to Princeton to his studio. He of course knew father very well, so I was like a member of the family there. Then we’d discuss what he was going to say to them and so forth. Then he would record it. I still have acetates of what he recorded. He of course asked what I was doing and I told him what I was doing. He told me that this is a very important work and I should keep doing it. He was very much interested that I should continue.

Chris Strachwitz: Did Einstein speak mostly in English, or did he speak in other languages?

Moses Asch: To me in English.

Chris Strachwitz: On the broadcast.

Moses Asch: English. No, the broadcasts was mostly Yiddish.

Chris Strachwitz: Those acetates you would then take to the broadcast station?

Moses Asch: That’s right. Then they’d go to the broadcast station. The broadcast station was stationed in Boston at the end of Boston now it’s become WGBH, I think.

Chris Strachwitz: It was a shortwave at that time?

Moses Asch: Shortwave yeah, to all those countries. Oh yeah. Then sometimes he would do it in German, but I know mostly it was done in Yiddish and English. He had a very good sense of English.

Chris Strachwitz: Have you released any of those?

Moses Asch: No. Those are waiting for release. I wanted to release Gandhi. I have Gandhi, I have Einstein, I have a few of these people from that period I want to release as an album. I don’t have enough for an album, though. I don’t know if an album by itself would make so much sense but if I put all the freedom fighters together.

Chris Strachwitz: That’s right. A perspective of World War Two.

Moses Asch: World War Two yeah, where people don’t know much about it.

Chris Strachwitz: That’s true. People forget very quickly.

Moses Asch: He was one of my guides because of my father. Was very much of a supporter for what I did. He went out of his way to loan me money when I needed it. He felt that what I was doing was right. That’s very important. Very important. Without that you lose hope sometimes, you know.

Chris Strachwitz: Because considering all this amazing material you have produced, a lot of people wonder how can you spend much of your time in promoting the records or overseeing the day to day sales business but I know you do it, don’t you?

Moses Asch: That’s right. I’m the only one that does it. I come in Saturday to analyze my sales figures for the week and so forth. I divide my time that way. The first thing in the morning is this fellow…. shows me what’s out for the day from last night, then I tell them what to order. The second order of business is for me to be sure that I know that the production, everything is going smooth in production. Usually some foul up between label and printer and everything else. The guy that makes the masters. That takes me till about 12 o’clock. From 2 o’clock on it’s mostly relaxing and listening to new material. That’s how that works.

Chris Strachwitz: That’s great that you put in a full day.

Moses Asch: I try to do most of my heavy thinking work first thing in the morning.

Chris Strachwitz: You do have some secretarial staff that helps you with the production problems with label copy and the artwork?

Moses Asch: No, sir.

Chris Strachwitz: No?

Moses Asch: No, sir. That’s all my problem. I did have some secretary staff with my label copy and everything else, but it got all fouled up. It’s much easier for me to sit down at a typewriter and knock out the label copy than to tell someone what I want, right?

Chris Strachwitz: I know what you mean.

Moses Asch: That takes less time and less energy. I do a lot of yelling, but not so much lately. I have a very good report between my printers and the pressing plant and myself. Very good. That saves me an awful lot in number of hours. I usually deal with the man I’ve been dealing with who owns the place in the printer for 40 years so he knows exactly what I want and how I want it. I can just give it to him. I never worked with an assistant because that always fouls it up. For the pressing plant I talk to the person I’ve been talking to the last 20 years. There’s very little effort or time wasted. Everybody knows when I get on it, this is what I want, this is the way it should go and there’s no sense of discussion.

Chris Strachwitz: I was wondering if you could also for us mention, for the listeners, your plans for the future. I think you have a ……

Moses Asch: You mean for Folkways?

Chris Strachwitz: Yes, for Folkways in case you ever have to retire or slow down even.

Moses Asch: Right. Well, the plans for the future are the following: The Folkways records will be a non-profit organization controlled by a board of trustees, my wife, my son who’s head of the developmental college in the University of Alberta in Edmonton, the gal that runs the office and the monies, Marilyn Conklin and the accountant/lawyer who takes care of the taxes and other financial problems.

Chris Strachwitz: So they will continue to …

Moses Asch: … to function in their particular orbits, not in the general. It may be for them to general discussion as to a financial problem or how to solve it. No one will say to Mike, “Hey I don’t like that music, I don’t want you to issue it.” That will be his responsibility. No one will say to Marilyn, “Hey, I want you to ship to that person.” If she says no, it won’t ship.

Chris Strachwitz: Because she certainly has her experience of that.

Moses Asch: I think that it should work out, and all the money coming into Folkways outside of royalty payments will be for the purpose of perpetuating the material. There should be enough money to keep going for quite a while. Meanwhile, there’s still 1800 records that are always in print and always sell. That’s a good backlog. The one fear always is that someone may decide to sell the …….. be offered an awful lot of money just for a few of the items that someone would think will … they could promote. I don’t think with this setup, these people are dedicated to what I’ve done.

Chris Strachwitz: Good. Because like you mentioned if a big company would buy some they would certainly bury the rest

Moses Asch: Oh, sure.

Chris Strachwitz: Columbia and RCA certainly could be even greater than Folkways if they tried to, but they certainly don’t seem to make any attempt in that.

Moses Asch: Not at all. What the bottom line is in the report to the stock brokers, stock holders, whatever.

Chris Strachwitz: OK, that’s good. Thank you Moe Asch.

Moses Asch: Thank you.

Chris Strachwitz: That could go on forever, but …

Chris Strachwitz: (VO): That was basically an edited chat I had with Moses Asch of Folkways records about a year ago or more in my car. So excuse the noises and …