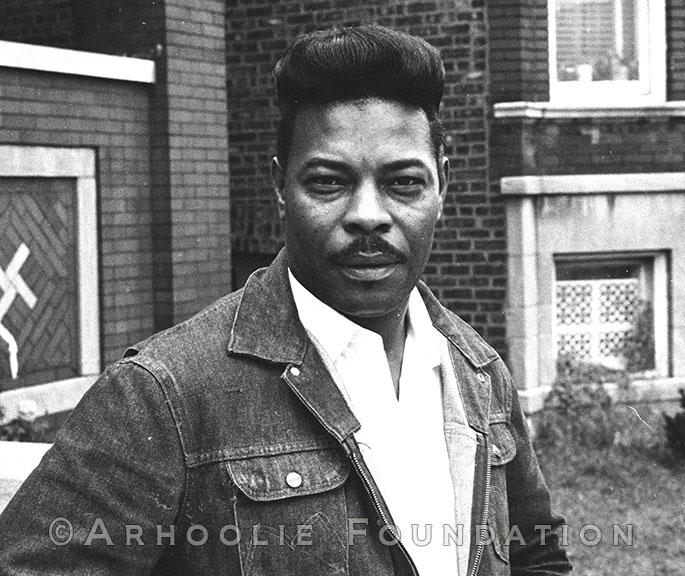

John Littlejohn Interview

“So when I got 14 years old, my father won a guitar in a crap game. He asked me – He really didn’t give it to me. I’d catch him going from the house and I’d grab it, you know. The first tune I learned how to play was – I heard Lightning Hopkins playing this tune – Baby, Please Don’t Go.” … “I heard him playing that, and that’s the first tune I learned how to play. When I see him coming, I’d lean the guitar back in the corner, you know, just like nobody touched it.” – John Littlejohn (John Wesley Funchess, 4/16/1931 – 2/1/1994)

This is an interview originally recorded for research purposes. It is presented here in its raw state, unedited except to remove some irrelevant sections and blank spaces. All rights to the interview are reserved by the Arhoolie Foundation. Please do not use anything from this website without permission. info@arhoolie.org

John Littlejohn Interview Transcript:

A Note About the Transcriptions: In order to expedite the process of putting these interviews online, we are using a transcription service. Due to the challenges of transcribing speech – especially when it contains regional accents and refers to regional places and names – some of these interview transcriptions may contain errors. We have tried to correct as many as possible, but if you discover errors while listening, please send corrections to info@arhoolie.org.

Chris Strachwitz: You know I like to get a little bit of the story behind you. You know, where you came from. I might as well just start from the beginning. What’s your birthday? When were you born?

John Littlejohn: 1931. April 16th.

Chris Strachwitz: Where…you were born in…

John Littlejohn: Jackson, Mississippi.

Chris Strachwitz: Jackson Mississippi

John Littlejohn: Yeah, it was in Jackson.

Chris Strachwitz: Jackson, Mississippi. Did your parents play music at all? Do you remember?

John Littlejohn: Let’s see…nobody in my family played an instrument.

Chris Strachwitz: Do you remember when you first heard something that made you want to play?

John Littlejohn: Yes, I did. I went to a fish fry one night. In those days, it wasn’t no electric lights and they had lamps and I heard ………up there and I think his name was Henry Martin and he was playing. Man, that guitar sounded so pretty. I got that sound in my ears.

Chris Strachwitz: Was that in Jackson?

John Littlejohn: This wasn’t exactly Jackson where the fish fry was. That was out at a place…

Chris Strachwitz: Was it out in the country?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, it was out in the country. Place called Raymond, Mississippi. That’s not too far from Jackson.

Chris Strachwitz: Were your parents working on farms? How did you happen to…

John Littlejohn: Well, yes.

Chris Strachwitz: I think most good Blues seems to come from the country.

John Littlejohn: They was in this…they was on a farm.

Chris Strachwitz: Were they sharecroppers?

John Littlejohn: No, they were working for a white guy name of Allen McNair.

Chris Strachwitz: He was a plantation owner there?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, he was a plantation owner. He had a big nursery farm, which he did it all. Cotton, corn, he did it all. He had a big pecan grove. He had pecans. You know, when you’re out there, you’re in pecans and peaches and things like that, you hear different sounds and things that crossed here. Birds….you know, things like that. Getting back to this guitar, I never heard a sound like that before. From that day to this one I haven’t had one out of all the music I ever heard.

Chris Strachwitz: Was he playing with a slide?

John Littlejohn: He wasn’t using a slide. He was using some music I say before me, and you, and my father was born. But it was a sound that nobody knows today. He’s dead and gone but nobody’s got that sound. But I’ll always remember that. I’ll never forget it.

Chris Strachwitz: Roughly how old do you think you were when you –

John Littlejohn: I was somewhere between 11 and 12.

Chris Strachwitz: Just a young, hardly a teenager. I guess you don’t recall any of the songs that he did, do you?

John Littlejohn: I believe one of those songs he was singing, a particular one that I had really wanted to explain, I can’t put it down because it’s been so long. I think one of these songs I can remember, but I can only remember the first of it. He says, “Mama don’t you tear my clothes.”

Chris Strachwitz: “You can push and pull all night long.”

John Littlejohn: Yeah, that’s it.

Chris Strachwitz: I’ll be damned.

John Littlejohn: I remember he was playing that. He played so much stuff. You know I’m eating those fish sandwiches, you know.

Chris Strachwitz: That was a guitar player there?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, his name was Henry Martin and him and my mother and father grew up together.

Chris Strachwitz: I see.

John Littlejohn: But he was playing, the music he was playing was back in his young days. That’s been quite a way back.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you go to school in that part of the country? Or did you have a chance to go much to school, working in a place?

John Littlejohn: I didn’t, really. I didn’t get a chance to go to school. I should have, because I wasn’t like a city boy, you know, when work came in. If you couldn’t pull a hoe, you could really catch some water. You could do something.

Chris Strachwitz: So you worked pretty hard all your life. Did you start playing after that pretty soon, or when did you get your first –

John Littlejohn: Well, I’ll tell you, I wanted to play an instrument so bad, and at that time I never could get over 75 cents to a dollar in my pocket.

Chris Strachwitz: How much did they pay you a day? That’s about what they’d pay for a whole day’s work?

John Littlejohn: Well, what I was making a day was 40 cents a day toting water.

Chris Strachwitz: Toting water. Was that on a construction field, or what sort of –

John Littlejohn: No, it was the people out there chopping down those peach trees.

Chris Strachwitz: And you were bringing them drinking water.

John Littlejohn: I was carrying them drinking water.

Chris Strachwitz: I see. And they paid you 40 cents a day. But I mean, did you live on the place, did you get a house and food for free?

John Littlejohn: No, you had to buy your own food. They gave you a house to live in.

Chris Strachwitz: But you still had to buy your own food.

John Littlejohn: That’s right.

Chris Strachwitz: You’d wind up eating a lot of pecans.

John Littlejohn: Well, to tell you the truth about it, if things today was as good as they was then, I would rather keep on making the 40 cents. You could get more. You could get more for 40 cents then than you could for 15 dollars today. In those days you could go to the store and get a penny loafer shoe. Or you could take a penny and go get five suckers. It went up to a nickel. You could only get five suckers for a nickel.

Chris Strachwitz: I guess people didn’t care so much about clothing down in the country. Long as you had a pair of pants and a shirt.

John Littlejohn: Long as you had a pair of pants and a shirt, know what I mean, you had it made. Actually, there was nowhere to go. Only time you see a person with a suit on, he was going to church or a funeral. A lot of them didn’t have a suit.

Chris Strachwitz: Do you remember how long you worked at that place? What did you do after that?

John Littlejohn: I stayed there somewhere till I got 15 years old. When I got 15 years old I was making somewhere around a dollar and a quarter a day.

Chris Strachwitz: That was already during the war, wasn’t it?

John Littlejohn: Yeah. I left there and went to Jackson. Got a job on an ice truck, hauling ice.

Chris Strachwitz: What kind of truck?

John Littlejohn: Ice truck.

Chris Strachwitz: Oh, an ice truck. Oh, yeah. Did you deliver ice?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, I-C-E. Ice.

Chris Strachwitz: For the old ice boxes they used to have?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, the old ice boxes. They wouldn’t let you have too much money. What the company would do, would publish these books, stamp books. They would sell out most all your customers with the book, and when you delivered the ice you’d just get a ticket out of the book.

Chris Strachwitz: They didn’t trust their drivers, or deliverers?

John Littlejohn: Well, those people, they didn’t trust nobody.

Chris Strachwitz: You know, I noticed that even still today, driving through the South, you know, there maybe two guys working at a gas station, one colored guy and a white guy. The colored guy will be pumping in your gas, but the white guy’s collecting your money.

John Littlejohn: Collecting money and watching. That’s right. He fixed the flat, the white man collects the money.

Chris Strachwitz: Where you already picking a little guitar then? Did you have a guitar by the time you were –

John Littlejohn: No, it really didn’t break down until – The truth about it, I’d leave town and come out and visit my mother over a weekend. I wouldn’t have too long a stay. My father, he was a gambler, and he used to win quite a bit of money. He used to win, sometimes over the weekend he had three or four hundred dollars. That was a lot of money.

Chris Strachwitz: I guess so.

John Littlejohn: ….At that time he had four or five hundred dollars. So, to tell you the truth about it, I don’t really know what he’d done, but I know he kept plenty of food at home and we went to school clean, starched and that. It wasn’t quite as bad as most of the kids around there, you know? A lot of them, their knees was out, they looked like – Well, I can’t say they looked like the people wasn’t trying to do nothing. I can say they wasn’t able.

So when I got 14 years old, my father won a guitar in a crap game. He asked me – He really didn’t give it to me. I’d catch him going from the house and I’d grab it, you know. The first tune I learned how to play was – I heard Lightning Hopkins playing this tune – Baby, Please Don’t Go.

Chris Strachwitz: Oh yeah.

John Littlejohn: I heard him playing that, and that’s the first tune I learned how to play. When I see him coming, I’d lean the guitar back in the corner, you know, just like nobody touched it.

Chris Strachwitz: He didn’t play it, though, did he?

John Littlejohn: No, no. He just had it. He won it in a craps game and he brought it home. Whatever they’d win, they’d win clothes off people’s back, they’d bring it home. That’s right. Anyway, he won this guitar, and on and on and on I’d mess with it every time I’d catch him gone. My mother, she would – No sooner I’d hit a snappy little tune that sounded real good to me, she would walk up going, “Where you going to put that thing?” So I’d put it down till she’d go out the back door. What’s she doing? I’d grab it again. So they finally caught me, caught up with me. My father, he said, “You can go on and have the guitar. You can play it if you want.”

So at the present time I would worry around the house. I would get on their nerves. They was living right on a railroad track. It was about 200 yards out in front of the house. Twelve, one o’clock I was 15 years old, I was sitting out there. I was 14, soon after I got the guitar I had a birthday. I was 15 years old and I went out on the railroad at night and just sit out there and just played. Cause the things that I’d heard, I had it in my head, I’d try to do it on the guitar. I kept on, kept on, kept on, till I started making things add up.

I was out there bothering nobody. I was out there by myself. Of course, it bothers them at the house, and I’d leave the house, no sooner – When they’d leave off the field it would be just dark. I wouldn’t have even eaten anything. I’d come home and grab my guitar. So that’s the way I got my start.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you hear any of the guys playing around Jackson? Or really not too much, you just – the jukebox, radio or something.

John Littlejohn: Well, I heard most of it- In them days you didn’t hear records played over the air like today. In those days only thing you could hear was a jukebox, and just some of those places you couldn’t go in. They wouldn’t let you in there. You could stand outside and listen. Some of them you could go in, some of them you couldn’t. All these places I could go in then I had to be 16 years old – I got to be 16 and I was helping my brother on the ice truck – was places that he’d deliver ice and then we’d go back that night. They’d know us. …. Because you see, he was only two years older than I was. He could go in, but me being his brother, I could go in. He was grown. He was 18.

Chris Strachwitz: How long did you stay there? Do you remember when you left – When did you leave to come up to Chicago?

John Littlejohn: I left there in ’49. I left Jackson in ’49, and I left and went to Blytheville, Arkansas.

Chris Strachwitz: To where?

John Littlejohn: Blytheville, Arkansas.

Chris Strachwitz: Why’d you happen to pick that place? Did you know somebody that was there?

John Littlejohn: I didn’t know anybody there. I’ll tell you what happened. A friend of mine, we left. When we left, we stopped in Blytheville, Arkansas, and that’s where we –

Chris Strachwitz: Got stuck at.

John Littlejohn: Got stuck at. They was paying 15 dollars a row for chopping cotton. So we chopped out a row of cotton a piece, we had 30 dollars together. It wasn’t nothing but Johnson grass.

Chris Strachwitz: It was all Johnson grass?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, couldn’t nobody tell you where you were, they’d look out there and see some grass. When we got to the end of the row, we worked all day, but we was in another little town.

Chris Strachwitz: Is that right?

John Littlejohn: That’s right. The man’s standing out there at the end of the row to pay off everybody.

Chris Strachwitz: I’ll be darned. That must have been a long damn field.

John Littlejohn: The truck picked you up and took you back to Blytheville. Man, you’d be somewhere around 10 or 12 miles from home. It was worth 15 dollars. That was more money than I’d ever made in my life. We got in the – a truck was leaving going to Solon, New York on a cherry farm, so we caught the truck and left out of there the next two days. Caught that truck, there was a bunch of them on that truck.

All right. We headed out to Solon, New York to a cherry farm. You know there they’ve got a big building like this, something like ……. people sleep on them, this room on the floor, some sleep on that room on the floor. If it was me and you, and we had another friend there, we’d all sleep in this room together on the floor. So they had a place in there that they could cook. They had some women’s cooks. Everybody’d get a woman and 50 cents a week, and she would cook for everybody. I think it was a dollar a week for everybody to throw in together and get their food.

So I went up there, but before we got there the truck broke down. We spent the rest of the night there on the highway. The guy was getting 25 dollars, and he about 50 or 60 of us on that truck. He called a man and told him he had broke down. The man said, “I’ll get you someone out there right away.” It was about 3:30 when the truck broke down. I forget what town we were close to, but he walked up to that town to call. Around 9:30, 10:00 somebody was out there, you know. He had told them what was wrong with it. They brought the right thing, fixed it, and took off.

Two days later I saw some pails or buckets, something like that. You get that full of cherries. You only make 20 cents.

Chris Strachwitz: For a big basket like that, you only got 20 cents?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, what you call a pail. 20 cents for that. If I didn’t have some money in my pocket, I’d starve to death. I couldn’t get but two of them a day. There was some people out there picking three or four of them things a day. I swear I couldn’t get but two.

Chris Strachwitz: Well, you were used to chopping cotton, I guess you were pretty good at that.

John Littlejohn: No, I tell you, I was used to carrying water. That’s what I was really doing. I thought about that, too. I could have stayed there and carried water for all of this.

Chris Strachwitz: Yeah, cherry-picking, did you have to climb up on a ladder?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, some of them you have to climb up on a ladder and get out on the limbs, and you can’t get too far out there or you’ll break the limb off. You got somebody along there watching you.

Chris Strachwitz: Was that a colored guy who got the people together to go out there?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, that was a colored guy. He got 25 dollars a head. Had his own truck, taking all those people up there.

I left there – I didn’t stay that long. I left there and went to Rochester, New York. I got a construction job there. I started driving a bulldozer. A bulldozer is no different than a …… You guide a … with a steering wheel. A bulldozer you guide with these levers. I knew about that. I used to push over trees and things with that. The guy I was working for, I can’t recall his name now, but he was building a golf …… out there, and it was a big one. I started working for the guy, me and my friend. I was making 149 dollars a week. The man, after we finished that work for him, for around 8 months, we finished and everything and he begged me to go to Florida, but I didn’t want to go back south. He said, “Look, if you go I’ll give you 200 dollars a week.” I told the man, “No, I can’t go back thataway. I just don’t like back that way.” I left that 200 dollars a week. The man wrote me after he left Rochester. I was living, I think it was 53 South Joseph Avenue in a hotel there. I got about 15 letters from that man after he went to Florida. He even sent a money order. I sent the money order back. For me and AC to come on down there.

Chris Strachwitz: Who was AC?

John Littlejohn: That was a friend of mine. That’s the one, we left together.

Chris Strachwitz: He didn’t play music?

John Littlejohn: No, he didn’t play.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you ever play during this time at all?

John Littlejohn: No, I didn’t play after I left Mississippi. I didn’t play any.

Chris Strachwitz: You didn’t even have a guitar, did you?

John Littlejohn: I didn’t even have a guitar, because I didn’t carry it with me. I left there – I heard …… come from Chicago, no, from Gary. He told me, “Man, 149 dollars a week?” Now you seen, I wasn’t hip. I was green. Hear what the guy had. He had a paycheck, his vacation check, and another check he hadn’t cashed. He said, “Man, look. 149 dollars ain’t nothing. I work in a steel mill.” I said, “Yeah?” He said, “Man, I make 207 (270 ?) dollars a week.” I said, “Yeah?” The guy had about 400-some dollars. He had a vacation check, two paychecks. I wasn’t hip, I wasn’t paying attention. So he rocks, I looked at AC, he looked at me, said, “Well man, our job is gone to Florida. What do you think?” We went out to a pawn shop and bought a suitcase. We packed, we left, we caught the Greyhound bus. We came to Gary. I had an auntie over there, quite a few aunties over there, and I have an uncle over there. So we get together and everything and AC says, ………

I’m a grown man. I went to her house. She says, “Who’s you?” I said, “I’m your nephew.” “Nephew?” I said, “Yes ma’am.” “No, boy. I don’t know you.” I said, “Well, do you know Molly?” She said, “Is you Molly’s boy?” I said, “Yes ma’am. I’m your sister’s boy.” And my cousin said, “Oh, Julianne, you know him. You tried to get him and bring him up here when he was a baby.” He was older than I was. “Child, that’s been so long, I can’t even remember that.” I said, “Okay.”

I went down in the slums, but I didn’t know it, see. Went to a hotel and got a room. The few clothes and things I had got stolen. My money had done run out. I went to the service station and the guy said, “Yeah, I need somebody to work.” So I said, “Well, how much do you pay?” He said, “The best I can do here is 45 dollars a week.” 45 dollars a week? And I’d been making 149 dollars a week! And that’s where the “each to his own” came in. They had a place over there called …….. I got the job at Shell Service Station there, and I worked there for about 6 months. I went down to a place called (?) Music Store. I bought me a Gibson amplifier, I bought me a Gibson guitar, I bought me a mic stand, and a mic.

Chris Strachwitz: When was this? About 1950?

John Littlejohn: It was ’51. I went out there, this was road house, called (?) The only thing I could play was what I had accumulated along the line by listening, watching. I started playing for them guys out there for somewhere around – I was making 12 dollars a night. I got a little band together, two other pieces, just a trio, and I was giving Mr. (?) , I was giving him 15 dollars a week for all my stuff. I was working seven nights a week. It wasn’t a whole lot of money, but it was coming in so regular. From then on, people was coming from places around like Joliet, Chicago Heights, different places, they’d listen, they’d sit there and drink, they’d listen to me. They’d say, “How long y’all been playing?” I’d say, “Well, we’ve been playing together now about 6 months.” “How would you like to have some money? Big money.” I said, “What do you call big money?” He said, “I’ll pay you and your band, I’ll pay y’all 350 dollars a week, and you’ll only work three nights.” I said, “Did I understand you clearly?” He said, “I’ll give y’all 350 dollars a week, and that’s three nights, Friday, Saturday, Sunday.” It was Joe Howard, owned Club 99 in Joliet.

Chris Strachwitz: Club 99?

John Littlejohn: Yeah. I had a lady’s drummer, I had a guy named Jesse Williams.

Chris Strachwitz: Who was the woman? Was that Grace Brim, by any chance?

John Littlejohn: Who?

Chris Strachwitz: Grace Brim?

John Littlejohn: No, it wasn’t. No. See, you got three women drummers in Gary. One named Irene, she’s the little one, and then Grace, that’s John Brim’s little lady, and then this other lady’s Margaret Lamont. So she was drumming, Jesse’s playing bass, and after I got her I added Tommy Junior, boy who blew harmonica.

Chris Strachwitz: What was his name?

John Littlejohn: Tommy Junior. His name was Tom, we called him Tommy Junior, named Tom Mosley.

Chris Strachwitz: Tom Moses?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, he’s in Grand Rapids, Michigan now. We played out at Joe’s house somewhere around three or four years. We left there and moved up a notch. We left there and we went to Benton Harbor, Michigan. We was learning all these new tunes and things coming out of there.

Chris Strachwitz: Yeah, I guess blues were pretty big at that point.

John Littlejohn: Yeah, the blues, Muddy Waters …

Chris Strachwitz: Who were some of the other guys you ran into down in Gary?

John Littlejohn: I ran into Bo Diddley, yeah. I ran into Jimmy Reed. When I ran into Jimmy he was about to come out of the Navy. Jimmy was playing out at the roadhouses, too. He was living in South Chicago out there.

Chris Strachwitz: You didn’t have to go in the service, did you?

John Littlejohn: No.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you ever run across a guy called Bobo Jenkins?

John Littlejohn: Bobo?

Chris Strachwitz: Up in Michigan maybe.

John Littlejohn: Nope. Anyway, after I left the small farm and went to Joliet I started moving up. We started in listening jukeboxes and things and record players and things, and kept on learning different tunes, and just kept on and kept on till I heard Elmore James. After I heard Elmore James, I told a friend of mine Jesse, he was the bass man, I said, “Man, he’s trying to play like me.”

Chris Strachwitz: He came from the same part of the country. He came from Mississippi.

John Littlejohn: Yeah, he come from ……..or somewhere, I don’t know. Elmore was raised up around Jackson. Anyway, I said, “This man is playing like me. If I could get a chance to cut a record, I’d stop all this. You’d have to change your style some other way.” I really was playing slide before him, though.

Chris Strachwitz: But he was a much older man than you.

John Littlejohn: But he was much older. But I forget – Mike Merrill 3(?) out in Jackson, Mississippi is the one cutting it, on ….Street.

Chris Strachwitz: They put out that Dust My Broom

John Littlejohn: Yeah, I tried to get that woman to cut me but she wouldn’t cut me. I tried to get Vivian Carter – she was with Vee-Jay, her and her brother Calvin. At that time The Spaniels were popular. I tried to get her to cut me, and she told me I wasn’t good enough. I went to Chess for ten years, and I cut about 30 or 40 different styles of music there. He said I had to bring something different. ……… I changed the style again, he said, “You sound like Muddy Water.” I went back again, he said, “You’re Jimmy Reed.” I went back again, he says, “Now, where’d you get this style from? This is …..” I said, “What kind of style would a man have to have? You’ve got Jimmy Rogers, you’ve got Howlin’ Wolf, you’ve got Muddy Waters, you’ve got them all on the same style. You can’t …….. What kind of style do you want?” He said, “Can’t you play me some of that B.B. King stuff?” B.B. King was getting …….. He said, “Can’t you play me some of that B.B. King stuff?” I said, “I’ll try.”

I went back again after about two or three months. I came back with B.B. King stuff. He said, “That’s too close to T-bone Walker.” I didn’t go back to no more. I know he didn’t want to cut me in the first place. I should have caught the hint in the first place. But one thing about it. I can say this about Howlin’ Wolf, and I can say this about Sonny Boy Williamson. People can say what they want about people. A man has got to do something to me before I say something about him, or say he’s no good.

Howlin’ Wolf told Chess and Willie Dixon “Man, if y’all are gonna cut the man, why don’t you go ahead and cut him and quit jiving him around.” I was playing with the Wolf there.

Chris Strachwitz: You did play with Howlin” Wolf?

John Littlejohn: I was playing with him there. He said, “Why don’t y’all go ahead and cut the man, quit jiving him around?” Sonny Boy Williamson, before he died I …….. brought him back, he went out to Chess and he got about two or three hundred dollars. And he cussed Chess out, he told Chance, “Man, this man been running to you for ten years. Why don’t you give him a break? Why don’t you cut the man? Why don’t you sign? You done signed everybody else, why don’t you sign the man?”

(tape runs out)

Chris Strachwitz: I think we probably just ran out very briefly. So you did try to get with Chess and he wouldn’t do nothing. Let’s see. You did work with Howlin’ Wolf?

John Littlejohn: I worked with Howlin’ Wolf.

Chris Strachwitz: Did you play guitar with any of the other bands around?

John Littlejohn: I worked with Jimmy Reed a while when …..was going pretty powerful. Me and Eddie Boyd worked together, I worked with him. I worked with a guy named JT Brown. I worked with him. Me and Eddie Taylor, we called him Big Town Playboy. We worked together for three or four years. Buddy Guy worked together. AC Reed.

Chris Strachwitz: So you’ve been really working as a musician since 1952 or so.

John Littlejohn: Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz: Pretty steady all the way.

John Littlejohn: As I went on to say about Bernard Rodgers, he ………

Chris Strachwitz: Who was this?

John Littlejohn: Bernard Rodgers. Three or four months later the man was the best on the west side, and we were out of a job, we didn’t have a job, so he started playing with Wolf. So after he started playing with Wolf, he went and bought him a label and recorded himself and published it. Two years later he recorded for me. He recorded me, rather. I said, “How has this young man been working for me going to tell me how to record me? What the heck. He knows more than I know.”

Chris Strachwitz: What was the label that he put out? Do you remember the name?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, it was Margaret. Margaret’s Label.

Chris Strachwitz: Margaret Records?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, Margaret Records.

Chris Strachwitz: Do you remember the songs that you put on there?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, “What in the World You Gonna Do,” and “Kitty O,” “Jonny’s Jive,” and “Can’t Be Still.” He couldn’t do nothing with it.

Chris Strachwitz: Was that your first recording?

John Littlejohn: Yeah, that was my first recording I ever did in my life. He couldn’t do anything with it because he got sick after then. He went to Highland Hospital and he’s still out there. Bad, bad shap. Look like he’s still going the other way.

Chris Strachwitz: Is that right? What was his name again?

John Littlejohn: Bernard Rodgers.

Chris Strachwitz: He also played saxophone?

John Littlejohn: Yeah. He’s a tenor sax-playing hard. But see, if I’d known he was in the shape he was in, I wouldn’t have let him blow.

Chris Strachwitz: Did he have TB?

John Littlejohn: Yeah. I didn’t know he was in that shape, because I liked the man as a friend. It’s kind of hard for a man to play all that and no drink. Something. He would drink a little orange juice, something like that.

Chris Strachwitz: How long ago was that? A couple of years?

John Littlejohn: No – It has been two years ago, because he’s been in the hospital now somewhere around 10 months.

Chris Strachwitz: What other records have you made since then? I always like to find out about –

John Littlejohn: Well since then I made Muddy Tears, Just Gotta Tell, I Let My Money Go To My Head, 29 Ways To Get To My Baby’s Door. But that ain’t getting released. 29 Ways and I Let My Money Go TO My Head ain’t being released. …..

Chris Strachwitz: Well, I think we’ve got something to – Anything else you want to put on the – that people should know about your music?

John Littlejohn: Well, I can say this. I worked a lot of places that paid the band, and didn’t make a quarter. Didn’t make nothing. It was lucky that I had two or three dollars in my pocket to get back home. That’s how I have been to bands and things I have had. People don’t realize these club owners and a lot of these citizens, they don’t realize how hard it is to live out there on that road. Sometimes you can find a place to stay when you get through playing. When you get through playing you have all the money in the world. People look at you cock-eyed, or one-eyed, but if they only knew. Musicians have one of the roughest life in the world. If you’re playing a nightclub you don’t know who’s right, who’s wrong, ………. you don’t know what ought to happen.

Chris Strachwitz: I guess you’ve worked in some pretty rough ones.

John Littlejohn: I have worked in some rough ones, but the only thing I was looking at was the money. All I was looking at was the money. After I had learned how to play. Before I really got to where I could play mostly perfect and good, I was just playing from my heart. Now since I started getting paid, it doesn’t make any difference if I get any money or not. I just love it. But you know, people treat you so dirty. They’ll turn you against music other than anything else. They look at you like you’re dirt. But I can say this. Women and men across the nation, they wake up by music, they lay down by music, they can’t go out and have some fun without music, they got to have music. But they still look at a musician like he ain’t nothing, he dirt. That’s everyday.

Chris Strachwitz: Have you gone back south to play a lot?

John Littlejohn: No, I hasn’t been back thataway. When I was planning to go back south I want to go there different. Different sound, different attitudes toward people, you know.

Chris Strachwitz: Because you’ve sure got that Mississippi style in you. I guess you learned that when you were a kid. It stays with you, I guess.

John Littlejohn: It’s in my now, it’s in my bones. I just can’t help it. It’s something that’s a gift. You see, a lot of people don’t know, it is strictly a gift. When God gives you something He doesn’t give you that. You’re supposed to use it. They say God will take two steps to your one, but God gave you …….. help yourself. He ain’t gonna come put no money in your hand. He help you stretch, you gotta get up and go help yourself.

Chris Strachwitz: That’s true. Well, I think that’s – And you’re married now and have a couple of children?

John Littlejohn: Married now, and I’ve got three. Two boys and one girl.

Chris Strachwitz: But you said before you were thinking once about quitting music, but I guess you’re still – at the moment –

John Littlejohn: At the moment I was going to give it up, because everybody I talked to was giving me a rough time telling me, “Well, you’ve got to do this, you’ve got to do that,” and I thought I had done everything that could be done. I didn’t know there was anything left to do. Everybody giving you a different song or a different conversation or a different stroke, I didn’t have no money coming in, and I know there was people out there that can’t sing half as good as I can, they’re making all the money. I said, “He’s got to be a racket, or somebody knows somebody, or something. I know the man ain’t half as good as I am. And here I am ain’t working.” Can’t work. Doing all and they say yeah, a job will pop up. When you give it up, something will come up.