Arhoolie Foundation to Digitize Oster Field Recordings

Between 1956 and 1963, Dr. Harry Oster, professor of English at LSU Baton Rouge, roamed the back roads of Louisiana in search of traditional music. A background in literary folklore put him on the trail of French and Anglo ballads, but it did not take long for a much broader field of music and related culture to reveal itself: blues, Cajun dance music, African American old time fiddle tunes, creole catholic hymns called cantiques, traditional New Orleans jazz, Mardi Gras Indian chants, church services, informal jam sessions and religious gatherings, prison work songs and spirituals, children’s songs, street vendor cries, personal histories, and folktales.

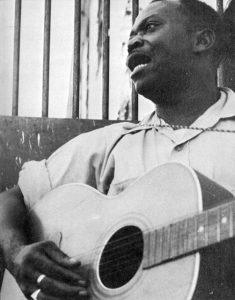

In 1964 Oster moved to Iowa where he continued to record regional music traditions including Czech, German, Norwegian, Scots-Irish, Amanite, Mennonite, Dutch, and Mesquakie. He also brought southern musicians such as Son House, Robert Pete Williams, and Reverend Gary Davis to perform at the University of Iowa.

Oster’s Louisiana recordings invite us into corners of America most of us have never seen, offering glimpses of a rural world evolving with the times yet inextricably bound to its plantation past. Some of them were issued on his independent label Folklyric Records, and later reissued on Arhoolie. The vast majority of them, however, remain unissued, unidentified and largely unheard altogether.

In 2006, the Arhoolie Foundation catalogued and digitized what we understood to be the last of Oster’s field recordings bestowed to us by his widow. In 2012 we discovered that many known recordings listed in discographies and mentioned in Oster’s writings could not be accounted for among the tapes in our collection, nor were they to be found in the few other repositories with which he had relationships. Further inquiries with his widow revealed several hundred additional tapes still in her possession: not only the lost sessions in question, but many more spanning the full breadth of his career beginning with his earliest Louisiana recordings of French ballads, Creole hymns and Cajun dances, all the way to the fiddle tunes, breakdowns and blues he captured in Iowa decades later.

Thanks to a generous grant from the Grammy Museum, we have hired Grammy-nominated audio restoration engineer Jessica Thompson to digitally preserve this long lost treasury of recordings. She writes, “A collection of field recordings like this offers an incredibly deep insight into historic music scenes. These recordings are not just the hits or the best takes. They contain all the interstitial information, which adds tremendous value—the conversations before and after songs, the audible evolution of songs among different performers and over the years, the interactions between Oster and the performers he recorded. These tapes wind up being primary source records of the music and culture of a particular time and place, which makes them of great historic importance to folklorists, musicologists and other researchers.”

Stay tuned for highlights from this completely one-of-a-kind collection.

Very interested in this. Hopefully it will annotated with photos and films.

This is such incredible news. When and how will it be possible to access these collections?

Extremely exciting news. Always interested in the breadth of your work.

Doug

I was familiar with Harry Oster’s work, but I didn’t know there was so much of it still unpublished. It’s exciting to think there will be new material available from these great departed artists. Thank you for doing what you do! I’ll look forward to hearing what comes out of it.

Rick

to this day when asked what is my favorite album i say ” country negro jam sessions.” it is also my favorite album cover- in its original format.

doctor oster’s contribution to field recording rivals the lomax’s. “i have to paint my face”, robert pete williams, butch cage and willie thomas, “barber shop rhythm” and on and on……

i can’t wait to hear what the vault will bring. thank you mrs oster, chris, smithsonian and ms thompson for this precious gift to the world.

‘

Thank you Arhoolie and Chris. Wonderful news! And thank you to the Grammy Foundation. Finally some of that money I spent for decades to be a NARAS member will be used for something other than an annual unwatchable TV extravaganza that concentrates on pyrotechics, lip-synching and dancing, while ignoring 98% of the music the Grammy’s supposedly cover.

Just want to note that NARAS and the Grammy Foundation have been supporting the Arhoolie Foundation for many years. They have helped fund the digitizing of the Frontera Collection, the digitizing of the Chris Strachwitz interviews, and now the digitizing of the Oster Collection. They also acknowledged Arhoolie Foundation’s founder Chris Strachwitz by awarding him their Trustees Award in 2016.

Oster heard someone singing “Smokestack Lightning” and thought it was a FOLK SONG. Of course, the informant singer had learned it off a juke box playing Howling Wolf. Leastwise, that’s how I heard the story. A FEEDBACK LOOP in the FOLK PROCESS…!

Firstly, I’d like to echo another contributor’s comments. “Country Negro Jam Sessions” was one of the first recordings of authentic Black music I heard, many years ago, and I have been an ardent Blues fan, and performer, ever since. The digital preservation project is wonderful news, but without trying to sound too negative, with the recent dizzying progress and changes in technology let’s hope the present digital system is not eventually replaced by another, rendering the newly preserved treasures as obsolete as 78 RPM records! Fingers crossed!

When will these recordings become available? And when will they appear in Arhoolie’s catalog?

I was fortunate in my teens, during the mid-1960s, to buy Oster’s ‘Angola Prisoners Blues’ on a whim. After that his ‘Country Blues’, ‘Country Spirituals’, and ‘Those Prison Blues’ compilations. Anything that had Oster’s name on it was good enough reason to hear it. This project is exciting news!

Congratulations, All! It is wonderful that more people will soon be enriched by Dr. Oster’s great works .

This is wonderful news.

Great news.

Please give my best to Tom Diamant, who I’m sure is involved in this effort up to his neck. When Tom and I were at University of Illinois in 1964-65, Archie Green had Harry bring Robert Pete Williams to CHampaign. Tom and I both got to see him then. It took me years to understand what it was I was looking at, but I think Tom got it right away.

blows my mind that you continue to discover wonderful, historic music from the past…

At the Association for Cultural Equity, we are of course thrilled by and applaud Arhoolie’s and the Grammy Museum efforts.

si pudiera compartime la delos braceros ay que suerte tambiem la del bracero y mamapola

si puede con partir unos de de los morenos que se llama la piedra lisa si fuera tan amable de enviarlo joelzanches1234@gmail.com

I knew Harry when I taught ethnomusicology at the Univ. of Iowa in the latter 1990s and 2000s. By the time I arrived Harry no longer was bringing in musicians to perform and had retired from producing records on his pioneering Folklyric label. He was in the English Department, no one in the Music or Anthropology Departments knew of him, and I only found out by a chance mention of his old friend and mine, blues pianist Erwin Helfer (in Chicago) who knew Harry from when he lived in Louisiana for a short while. Harry was sweet, friendly and so humble in describing how his interest in Cajun music and culture sparked the first surge of interest by Cajuns in documenting and projecting their culture. He said he was quite amazed at the impact his “noodling around” created in the Cajun community, a wave of validation by Cajuns of their heritage that took him quite by surprise. As mentioned above, he expanded his documentary interests to a host of musical cultures when he lived in Louisiana, and he continued his work to some extent in eastern Iowa. He always focused on lyric content, he wasn’t a musician and in his gracious way denied understanding any musical content. I invited him into several of my undergraduate classes where he held students’ interest with sometimes risqué examples of song lyrics. I visited with him in his home several times and as I realized how much material he had collected I tried to convince him of its value — he was a pioneer folklorist of Cajun and so many other communities. I encouraged him to organize his somewhat scattered files and recordings better and consider housing them in an institution. I wasn’t successful in that, but now am very heartened to see that his groundbreaking investigations are being preserved and made available to everyone. As he described himself he was a bit of an accidental cultural anthropologist, but his dedication and open-minded attitude to others’ culture has left us a tremendous legacy and window onto a place and time that would have slipped by without his efforts. Thank you Arhoolie for another great contribution to preserving folk-rooted musical culture.

Harry was on my dissertation committee at the University of Iowa during the early-to-mid 90s. He made two trips to my study area in southwest Louisiana and we conducted hours of taped audio and visual recordings of Cajun musicians and the rural Mardi Gras celebration. We did similar fieldwork on the Gui Annee celebration in Prairie du Rocher, Illinois. An article based on our research was published in the Journal of American Folklore in 2001. I have some of this material but most of it should be in his collection. So, there is considerable material to work with beyond what he is widely known for collecting in Louisiana in the 50s and 60s..