Ry Cooder Interview

“Once you can see somebody play, I’ve always found this to be true, it illuminates the whole situation, how they hold the instrument, how they physically go about doing these things. Copying notes off a record is pointless. You got to know how they get themselves in a physical state and then things happen, they just seem to happen, that you know how that’s done or you can understand how it’s done makes a whole lot of difference. That’s why filming musicians is such a good thing, because then if you can’t go where they are, if they’re dead, you look at this film and you really understand a lot, just looking at a guy, you understand a lot.” – Ry Cooder, from the interview

This is an interview originally recorded for research purposes. It is presented here in its raw state, unedited except to remove some irrelevant sections and blank spaces. All rights to the interview are reserved by the Arhoolie Foundation. Please do not use anything from this website without permission. info@arhoolie.org

Some interviews contain potentially offensive language, including obscenities and ethnic or racial slurs. In the interest of making this material fully available to scholars and the public, we have chosen not to censor this material.

See below photo gallery for a transcript of the interview

Ry Cooder Interview Transcript:

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah, Ry, you know, when did I run into you the first time? Wasn’t it way back at the Ash Grove? Did you ever play with the group that used to hang out at the Ash Grove?

Ry Cooder:

Well, me and Taj had a group. No, I don’t know. I think… Yeah, that’s where you were, that’s where I first met you. Why don’t we just put the machine down? It’s better that way.

Chris Strachwitz:

You think it’ll-

Ry Cooder:

You don’t have to worry about it. Oh, yeah man, we’re close to this thing. I had a group with Taj Mahal, it was in the ’60s, like ’67, you know, I mean, that’s my recollection of when I first started to pick up Arhoolie records I was in junior high school and I was just out of high school when I had that group with Taj. So about six years or seven years before then I first got that Big Joe Williams record, Tough Times, you know that one?

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah.

Ry Cooder:

That was one of your first records.

Chris Strachwitz:

I’m sure.

Ry Cooder:

So that’s my recollection of Arhoolie, goes back to that one. And then the Mance Lipscomb records came shortly after. We used to put about a record out every six months, it seemed like at the time.

Chris Strachwitz:

What kind of music were you playing at that time?

Ry Cooder:

I was playing guitar, blues and mandolin stuff. A lot of Sleepy John Estes and bottleneck, I just started to learn when I was 15 or so, which wasn’t anybody around to show me how to do that until Ed Pearl started to get some of those guys who were suddenly being rediscovered and funneled through that venue and then it became very easy, once he started doing that, bringing up Gary Davis and all those people.

Chris Strachwitz:

Now you found it easier to watch somebody-

Ry Cooder:

Well, that’s it. Once you can see somebody play, I’ve always found this to be true, it illuminates the whole situation, how they hold the instrument, how they physically go about doing these things. Copying notes off a record is pointless. You got to know how they get themselves in a physical state and then things happen, they just seem to happen, that you know how that’s done or you can understand how it’s done makes a whole lot of difference. That’s why filming musicians is such a good thing, because then if you can’t go where they are, if they’re dead, you look at this film and you really understand a lot, just looking at a guy, you understand a lot.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. It struck me, I remember when you came down to Texas and you had learned how to play “La Nueva Zenaida,” I always assumed that musicians learned music by osmosis kind of, I never realized how hard you had to work-

Ry Cooder:

Oh, it’s very hard.

Chris Strachwitz:

… To figure out all the notes and how they-

Ry Cooder:

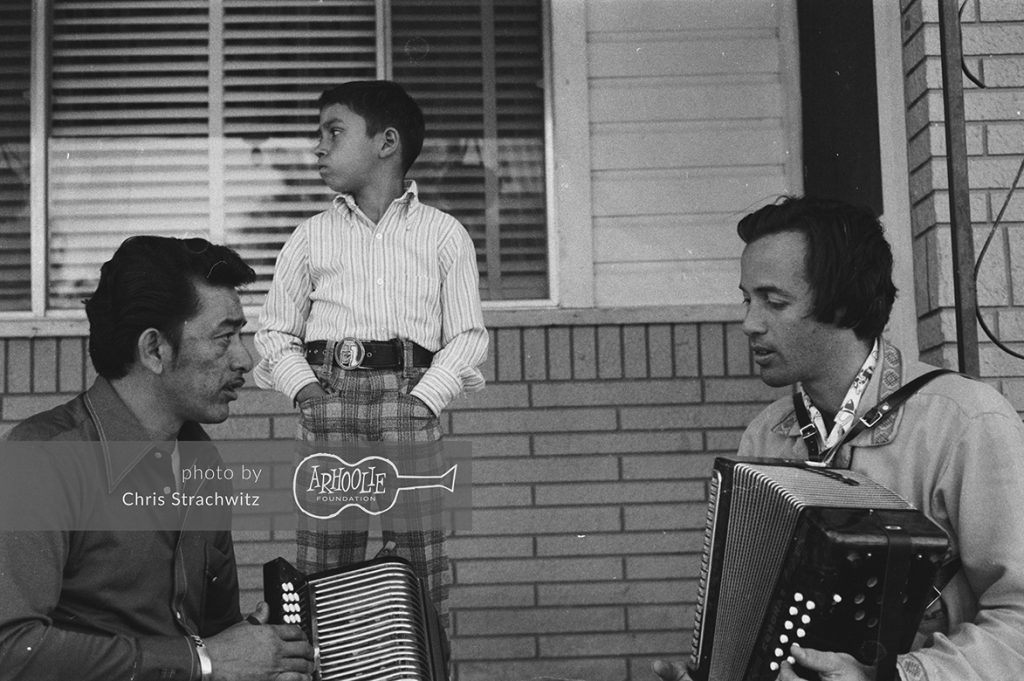

Yeah, I’m not an accordion player, so I knew that the instrument was… There was something technical with that accordion that you had to understand in order to make it sound like that. Because piano accordion is just a matter of rote technique. But with that little button accordion, I listened to these records and I could hear this popping and the finger technique on the keys was something that you just had to see it done, and the chords. And then when I saw somebody play it, right away I realized in an instant that it was a fingering technique they had worked out, so they could get the chords they wanted and with their hands, they had to space them a certain way on the keys, and then as soon as I saw this guy was a friend of Toby Torres play one of those duet guys a two-accordion group, you know what I’m talking about, forget their name.

Ry Cooder:

Then I’ve had it all straight in my mind, I went home and worked on this every day for six months with these records, having seen this guy play for five minutes, I knew how to go about doing it but it was difficult, very hard primitive instrument, and then these guys get so good on it. Then they breakthrough, and they have this tremendous technical ability to play a very primitive instrument, you know what I mean? And it’s very difficult.

Ry Cooder:

The piano for instance, highly technical instrument or something, or like the French horn. And so with a weird instrument, like the guitar or the button accordion it’s just you versus it, and you have to transcend the limitations of this silly little instrument. I mean, Hohner designed that thing to play in three keys, and those guys play about six keys on there. Now how they do that is just they… It’s willpower. And that’s how they want to sound and they just go about doing it that way. It’s pretty interesting.

Chris Strachwitz:

Can you think of any, I can stick some records in here and there, I’d like to do a program on this, and if you think of some records that… Like if you were at home, if you pull out a record to illustrate something, it’d be great.

Ry Cooder:

Well, I think the clearest example of what that instrument in an idealized way sounds like is Los Alegres, that guy has a very clear, simple style, but it’s a very beautiful use of the instrument, see. Now, on the other hand, you’ve got that guy, Ruben Vela, who plays a real fancy kind of over… His style to me, it’s like Tex-Mex ghetto switch blade nasty style that he’s got, and he gets a really kind of sleazy sound out of this thing, and he goes for the technical, to me, he’s found a way to make this thing- to squeeze it, and it almost sounds like it’s being limited. I mean, he’s like going through this really extreme kind of syncopation.

Chris Strachwitz:

He’s very advanced.

Ry Cooder:

Very syncopated and very advanced player, see. So he’s at the other end of the scale, if you’ve got Eugenio [Eugenio Abrego, accordionist for Los Alegres de Terán] on one side, the elegant kind of old rural sound, but perfect in a very perfect classical way. On the other hand, you’ve got this sort of urban city guy, Vela with this nasty, low rider kind of accordion that he plays and that illustrates what’s going on physically with that thing. And of course, people have to see it to appreciate it. Because when I play those records for people, they don’t in their mind picture this funny little red accordion. They always think of the big piano accordion, but this is not like that, see, it’s this small little intractable thing and they get in there and they take the reeds apart and file them down so that they have a nice little intonation. They tune them up pretty. It’s an amazing kind of a thing.

Chris Strachwitz:

You’ve pretty much spent most of your life in school with music haven’t you?

Ry Cooder:

Well, I always played, when I was in school, I mean that is to say public school, it was hard for me because I didn’t like being in school. So I begrudged the time I had to spend six, seven hours a day in those places, I just would go home and play and forget all about it, and try to relax, you know what I mean?

Chris Strachwitz:

Just play records.

Ry Cooder:

Yeah. If I hadn’t had the instrument, I think I surely would’ve ended up in a mental institution, but some people don’t adapt to these things. I never like being regimented and having to move from place to place in that way. So that’s something I always like to do.

Chris Strachwitz:

Did you grow up in Los Angeles?

Ry Cooder:

Yeah, actually West LA.

Chris Strachwitz:

What kind of stuff did you first hear when you were…?

Ry Cooder:

Well, I mean, my parents had records, they had records. I mean, classical music primarily. My first memories I have, I guess, are things like Beethoven quartets or something, which I guess for an infant is nice, kind of soothing, soft singing. But then I got attracted by things like Woody Guthrie records, which were also around the place and in those days it was politically significant, why people listen maybe to this kind of stuff, was some tie into left wing politics you see, which at age four or five, I guess I didn’t comprehend, but I like the sound of it. Especially like Guthrie with his strange little stories and those pictures that went with the records, the Folkways records had the photographs and the little pamphlet, made it very rich. I mean, it was very curious to me living in this kind of sort of normal middle class setting, what in the world, this was all about all these broke down looking people with their bed rolls and everything, it seemed very exotic. Still does to me actually.

Chris Strachwitz:

Were you folks into to sort of left wing politics?

Ry Cooder:

Well, yeah, this was something that divided up the country in those McCarthy days. You were either on one side of the fence or the other, and it was tough times and friends of theirs were blacklisted for one reason or another. And it was kind of a… I see now as being very dramatic, but I was very unaware, I mean this little child. But this music was around and friends of their certain couple that was friendly with them. The guy gave a guitar to my dad for me to try, and I had no idea there again, I was three and a half, four years old. [Tape pauses].

Chris Strachwitz:

I mean, I hope you don’t mind instead of doing a thing like this, I’d just like to-

Ry Cooder:

No, I don’t mind at all.

Chris Strachwitz:

Because, you’ve got a lot of fans, I think to me, you’re one of the more… You have an ear apparently of combining things, I feel of the you, real ethnic things and making it interesting for a contemporary audience. So do you think so?

Ry Cooder:

Well, I think so. Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

And, because the pure ethnic thing, I don’t think it’ll ever reach a wide audience.

Ry Cooder:

Well, no.

Chris Strachwitz:

I don’t think this ever has a chance to.

Ry Cooder:

No it’s to peculiar for folks.

Chris Strachwitz:

That’s right. It’s just too peculiar because we all come from a certain background and I think we have to be given thing that suits that background. Don’t you think so?

Ry Cooder:

That’s right, has to make sense.

Chris Strachwitz:

And has to make sense. So I think you’re a really an important person because you’re one of the very few who’s been able to combine that, to take elements of ethnic music and make it into your own, make it into a new, interesting sound. So I think-

Ry Cooder:

Well don’t you think so that, it occurred to me, along the way, I guess I always figured American music was interesting because it was a combination of things, because all these people came here or at least they were here and it’s the natural way of people in this country moving around and going from where they were from to a different place to live, which happened a lot. And things changed that way. And it’s when you get something like that, where one form meets up with another form and then you get a funny little combination and it produces something new and interesting. I figure that’s the context to operate in, try to do that in my own small way, you see.

Ry Cooder:

Plus, obviously if something is good and you hear something good and you think I can say to myself, I can use this, why not try it? I mean, nothing to be lost from trying. And if you’re smart, you can present things. It’s all a presentation. See, people will like something if they hear it right. If it’s presented wrong, they’ll hate it. Accordion’s a perfect example, if you said accordion to most people, most white, I’m talking again, white middle class Americans who buy albums, you know what I mean? In a mass demographic sense, Mexican music, they don’t like it, accordions, they hate accordions. They think Lawrence Welk, but that music, Tex-mex is a good example, very strong, hot vital and beautiful sound. It just has to be presented right, I think, and folks dig it. They think, “Oh, that’s wonderful, what an exciting thing.”

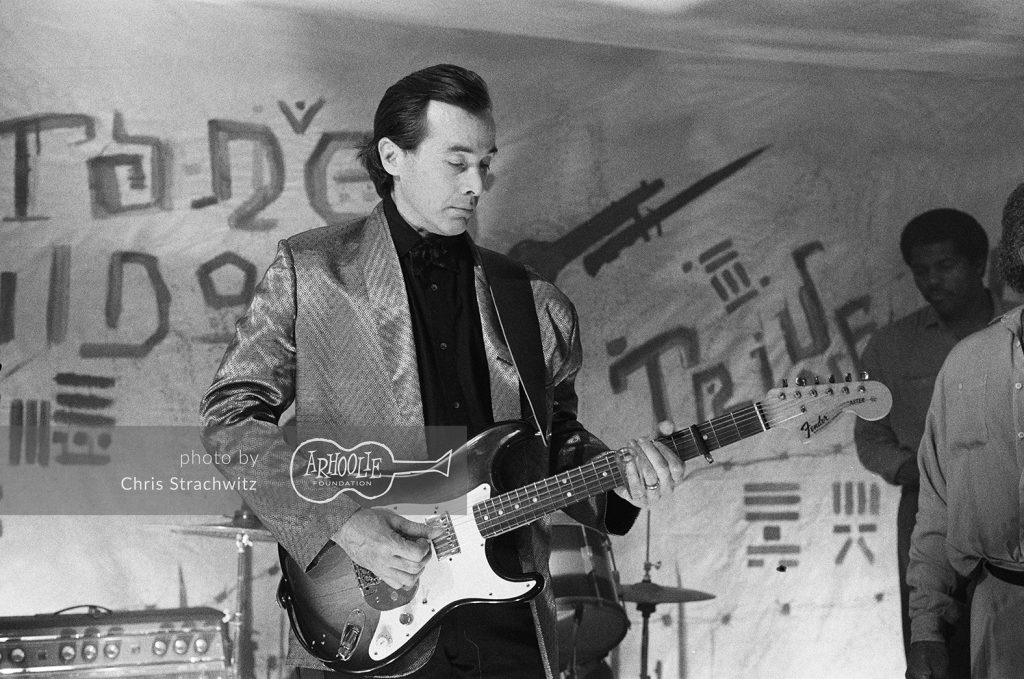

Ry Cooder:

Plus it’s good on stage when I had Flaco and them on the road with me, I mean people would sit down and we’d come out. The audience would look up and see these guys in these plastic leisure suits and the Black guys singing background, they just figured all this is going to be insane, it’s not going to work, it’s not going to make sense. And by the end of the show, everybody usually was pretty well into it. So that was a matter of presentation I figured, because I say I’m supposed to know what sounds good together. I think I can organize things pretty well. I’ve worked at it a long enough time. You get the hang of it after a while. And then the trick is to meet people halfway so you know what they like, pretty much, they like the Eagles, they like Billy Joel, they like Elvis Presley maybe, and so if you can somehow segue into that and do what you like too, then you’re doing a very good thing.

Ry Cooder:

And, I’m not trying to convert anybody because it’s an entertainment media it’s a form of entertainment. So you want to provide a show for folks or a record for folks that they can sit and enjoy. Now I think I’ve gone overboard sometimes and made some mistakes and got a little bit too hip for my own self in ways, and I found out by making mistakes, what was going to work out and what was strictly just too of crazy and weird. But I think that’s how you learn, and besides there always is room, even though pop music and popular music today is so galvanized and so homogenized, it’s almost taken all the regionality and therefore the individuality out of itself, you know what I mean? Still there’s room for things you can still get away with a lot of stuff.

Ry Cooder:

Because when they used to make those sun records with Elvis in those days, that guy, Sam Phillips, he figured if you could get a white guy to sing like a Black guy, you could sell it. White people have to see a white guy up there almost even today. They need to see somebody like them on that stage if he can… But put across something that’s exotic or strange so much the better. And so working for a record company like Warner Brothers, I was always very conscious of the need to participate in what they think of as being the record business. Otherwise, you’re fooling yourself, you should be on Flying Fish or Takoma, see and then that’s okay. But I like the idea of doing this thing on a major label and it’s almost like getting away with it. But at the same time folks like it and if they like it and the records can sell, then you’ve really accomplished something, I don’t know it’s just challenging, it’s like climbing a mountain again.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, you also got to make a living.

Ry Cooder:

You have to make a living, that’s right.

Chris Strachwitz:

And I guess it’s really no fun to starve all your life.

Ry Cooder:

No, it’s no fun to be poor. I mean, what I’ve tried to do is survive in the business by doing what I thought was good. And I mean, I’ve been making records on that label for 10 years now. So they’ve…

Chris Strachwitz:

Really, has it been that long?

Ry Cooder:

Yeah, it’s 10 years, 10 albums in 10 years. They’ve been good to me. And recently the things started selling more. I think the seventies was a real bad decade for me in certain respects.

Chris Strachwitz:

Because musically, I thought it was pretty good.

Ry Cooder:

Oh yeah, but commercially I wasn’t making a dime, and I think the reason was that was… I got a theory, that what happened in the seventies was all of the prerecorded history in the history of records had a continuity, led up to a certain point in the then all of a sudden solid state equipment came in multi-tracking and great sums of money combined to produce a high tech, high gloss kind of music. You see what I’m saying? It’s like this very expensive, fancy sounding pop records that came along in the seventies changed everybody’s- it’s pervasive, it’s everywhere. It’s the kind of thing you hear it everywhere. It’s like a little atmosphere it’s like in the elevators in gas stations and drug stores and restaurants, especially in your home, on the radio, on TV, you heard the same kind of sound all of a sudden, you know what I’m saying?

Chris Strachwitz:

And, I think it’s true what you’re saying that it’s become so expensive to record, it’s really ridiculous in a way it’s almost like the arms race.

Ry Cooder:

Well, it’s exactly like the arms race. So then what happened was hardware does generally lead everybody around by the nose, I think, you follow it and people who are making records say for instance, in a local regional context, like in the south, look at Hollywood and say, that’s the real record business, and they want to imitate that, they want to be like that. So they won’t produce more Fats Dominoes, or they won’t produce anymore of people like Clifton Chenier or somebody, they will try to get into that pipeline somehow, which in the end in results in something like the Grammys. And what they honor on the Grammys really is somebody who has accomplished and participated fully in that whole industry wide uniform state of the art situation, the better you do at doing that, the more you will… Nothing succeeds like success. If you spend 500,000 on an album, see which a lot of them do, let’s say for instance, pick a figure and then you go out and sell 5 million copies, that alone is a tremendous affirmation. So the music is the kind of music that, what they call what M.O.R., middle of the road, right. Exactly that point. I mean, it’s right in the middle it’s mainstream, it goes right down the line and it can appeal to everybody in a kind of a subliminal way, like Muzak.

Ry Cooder:

And if you understand that the business is set up like that now, it didn’t used to be, it didn’t use to have the little labels and they were recording who they had, and they were selling to a limited audience here in their pockets of different styles, being the continuity of that. Now you don’t have that so much anymore. So you’ve got to make a living, you got to somehow go along with the program, I do, if I’m going to stay on that record company. I mean, if I was out there now looking for a record contract, I wouldn’t have a chance, I don’t think.

Chris Strachwitz:

You mean if you were starting out?

Ry Cooder:

Yeah. I mean, it’d be hard now. Because, they would listen to what I’d do and they’d say it’s eccentric, we can’t use it. You won’t get on the radio, you won’t get air play.

Chris Strachwitz:

On the other hand, don’t you think that the audience has perhaps become more accepting? At least there is an audience worldwide now that is perhaps more open to unique and different things?

Ry Cooder:

I think so. I think in the eighties, especially, we’re going to see, having gone through this kind of thing, and people do tend to taste change and people change and the business is always going to be slow and lethargic in responding to that. But for instance, all this new wave punk rock stuff is something about cheap music that I kind of like, portable cheap music garage. And that’s where for instance, rock and roll started out any how. Fender guitars, little amplifiers, you just don’t need to have to be a millionaire to play this stuff. It’s three minute songs, four minute songs, a little record with a big hole in it. How expensive does that need to be? Some of the greatest records and ones that everybody sits around and say, how great, I mean, the stuff was made on two track tube boards and God knows what. So I think that’s a good sign, I think that the public taste, especially for going into a time of tough economic times, you’re going to see some response to that and that all has something to do with it.

Chris Strachwitz:

How did you get-

Ry Cooder:

It’s cyclical though as well.

Chris Strachwitz:

How’d you get interested in recording with Earls Hines and this jazz-

Ry Cooder:

Well, I thought he was a great musician, he’s such a wonderful childhood favorite of mine. And when I realized he was living and had returned to the scene, I waited for him to come through LA and he did. I called him and had found out where he was staying. So I knew all of his stuff and I figured I got one tune, this Blind Blake song that I bet he can play. Because it’s got the kind of semi stride beat and this is something he can wrap his head around, needless to say, he could. He’s very agreeable, and I said, “You don’t know me, but I’m a big fan, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. You got nothing to do today, let’s go down to the record studio.” He said, “Fine.” I picked him up. We went down there and had a real good time.

Ry Cooder:

And, that kind of thing can happen. I mean, musicians are very agreeable, generally. They like to get together. And that certainly is when you bring somebody two things, you bring, them a musical appreciation of them, you bring them a working situation in which it can actually bring forth a result right quick. In other words, I don’t want to take up your time, come to your house, drink your liquor and sit around, I’m offering some sort of work as a catalyst, an occupation that’s what it’s all about too, that’s that making a living thing on one level or another.

Ry Cooder:

And so things happen in a hurry, it’s efficient. And so whenever I’ve had any desire to play with somebody, I’ve tried to figure out how to put it into a work type mode, and then it always makes a lot of sense, especially to a guy like say Sleepy John, who needs to make money. He can’t stand to sit around and play it’s okay, but he needs to make some money too. Or some of these Hawaiian guys I mean, they’ll sit around all day, but if you want to do something with them and then you have a good plan, everybody likes that, it’s exciting besides.

Chris Strachwitz:

That’s a real important part of your role, I think is to sort of a catalyst, because there’s a lot of great talent sitting out there, sometimes it’s embedded in its own ethnicity and therefore never gets anywhere. Other times, like you say, with those Hawaiians, maybe they’re just simply, their life isn’t geared to going up and hustling all the time.

Ry Cooder:

It’s just not geared to it.

Chris Strachwitz:

But so often the beautiful things happen when somebody like you gets them together with something like any social relation, I guess, or like diplomatic whatever you want to call it.

Ry Cooder:

Yeah, it’s somewhat diplomatic. But the thing about musicians, they have this other perception which is the hearing and it cuts across economic, you don’t come in there as a representative of a dominant society or money, you know what I mean? You come in as a player with your instrument in your hand and that’s them too. And so you meet halfway and if it works, it’s really a lot of fun. I’ve played with some very strange folks and you always do something, and it’s that hearing it’s nice. I mean, you hear it come back, it’s good. And then you say goodbye, see you again some time when you see them again, you pick it up where you left off. It’s really a lot of fun. I like it, that makes life interesting for me, I get to go and see these things unfold. Because basically I’m doing it because I want to hear it myself, I’m curious.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, I’m glad you’re doing it. I guess I’m lucky but I make records, I get to travel around and I’m glad that you can do it with meeting musicians and getting to use them and they get to use your thing and so on. I think it’s a nice interchange.

Ry Cooder:

Yeah. It’s very nice really.

Chris Strachwitz:

I remember when we were down in Texas, I forgot how you… I think you were down there for quite a while with this one.

Ry Cooder:

Well, I came down a couple of times, and followed you guys around. And that was really great because since you’d scouted it out and knew where the gold was buried, so to speak, it cut back on the time it would’ve never been impossible for me to… It was an efficient thing. I mean, it was like you knew where to go, so here were these people it was just a matter of, I knew I was going to run into somebody who’d want to play with me, since there was a language problem to some extent. I mean a lot of them don’t speak English, I don’t speak Spanish too good, but it was amazing coincidence is what it was. Because I heard this stuff on the radio in LA and I said, this is different. It’s not mariachi it’s not tourist music, it really is strong. And I got to find out about this stuff. Not ever dreaming there was this whole culture thing down there, plus a really vital little recording scene. It’s really nice, it’s like fifties, it’s great, and this still goes on today, it’s nice.

Chris Strachwitz:

Just as many records as they were of R&B in the fifties, almost, it’s incredible how-

Ry Cooder:

Amazing isn’t it?

Chris Strachwitz:

…prolific that material has been. And let’s just go back a minute. I guess I’m always one of the sort of historian, you and Taj, who else was in this band? What are they called? What was it-

Ry Cooder:

We called ourselves The Rising Sun. It was not a very good group, but at that time, nobody was very good. The folk rock thing was just sort of seeming to be something and The Byrds were out there playing and The Doors, which was that other kind of thing. And then we got work because there was hardly any anybody around town who could actually call themselves a band, show up and play, respectably. So what we used to do was open these club dates for people like The Temptations and Martha and the Vandellas and these Motown groups or whoever, Otis Redding.

Ry Cooder:

That was quite a thrill, I mean you get to sit and talk to these people. And I was just out of high school, I didn’t know anything, I didn’t understand anything, but I knew who in the hell Otis Redding was. So, and then one thing led to another and then the group broke up and Taj went on to make records for Columbia. And I got started doing sessions, which was nice because that was something I wanted to do was be in the record studio and find out what in the hell that was all about.

Chris Strachwitz:

Who did you play behind?

Ry Cooder:

Well, I started working for Terry Melcher who was producing, he produced The Byrds and I played for him on, whatever he was doing, say like Paul Revere & The Raiders and some of that kind of stuff. And numerous people, I can’t even remember who they were, lots of stuff doesn’t come out or it’s never becomes known. And then I met Jack Nitzsche who was arranging for Phil Spector and people like that. And I worked with him because in those days, things were starting to change and they had figured out that sound effects, if you can play something weird, it can make their thing a little bit more interesting instead of five guitar players all playing the same thing.

Ry Cooder:

And if you’ve got a guy who plays bottleneck like me or rock and roll mandolin, which is just stuff I invented on the spot for myself to do. A guy says, “What do you want to play on this?” I see three guitar players say, “Why the hell play guitar? I’ll play mandolin.” “What’s that?” “So, well, it’s this thing. It’s a silly looking instrument.” But if you can figure out a way to make mandolin work on, an ordinary rock and roll record, well then these guys got happy. “Hey, that’s great.” And then they’d say, “Hey, can you come back tomorrow?” “Certainly.” So before I knew it, I was actually earning a living of sorts doing this and it was educational because I had no idea how these things were done, really. I had records, but it was always mysterious to me, how music gets through the wires and what really happens in there.

Chris Strachwitz:

Is there a certain record that you, pick sticks in your mind that you kind of liked that you played with rock and roll mandolin one?

Ry Cooder:

Yeah, I wish I could tell you it’s been so long. I can’t remember any of that stuff now. I remember doing it, but I don’t remember the names of the tunes because it’s that’s 12 to 15 years ago, I did all that.

Chris Strachwitz:

Actually, I think one of the nicest performances I ever saw you do was in Austin remember that benefit you did for Mance Lipscomb.

Ry Cooder:

Yeah, that was fine.

Chris Strachwitz:

All I remember was you were sitting all by yourself on a chair, I think, and you switched from mandolin to guitar and you sang something fierce. It was-

Ry Cooder:

Well, those were really the good days. I mean, I used to be it at a solo act. It’s very hard work at that, I mean to maintain that all the time, as you say, sitting in a chair and the times have changed and people don’t much want to see a guy sitting in a chair anymore, you know what I mean? That’s kind of over.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, you got to run around and-

Ry Cooder:

Well, you got to be up there. And besides I don’t record that material, so naturally if somebody buys a record of mine and likes it, they expect to see it on the stage. Rightly, don’t you think? But I remember that show, that benefit for Mance was fun because it was a reason for it. And of course, that’s show business, you help out somebody who needs some help, poor man laying there in that county convalescent home or whatever the hell it was. It was very sad, but I mean, it was a nice event, showed the film and Doug Sahm was there, and I always remember that. In fact, we played in that theater four weeks ago. They’ve rebuilt it, and they’ve reconstructed the whole thing and it’s restored inside and quite beautiful. Austin is still a good place to play, it’s a nice town.

Chris Strachwitz:

Do you think you’re going to stay with the band that you have now or do you plan on having another one of-

Ry Cooder:

Well, the band I have now is some friends of mine who we happen to be together for a time. They are a band, John Hiatt and his band, they go out and they’ll all be doing their own work, making their own record and all, but what I’ve come to think of is the best thing I do is play sort of R&B stuff, soul music if you want to call it something. I thought Tex-Mex R&B was a good idea. It worked for me, but it was hard to maintain because those guys don’t like traveling. They don’t understand the way things are, and it was a little hard for them to be on the road with me, two shows a night and seven nights a week, they weren’t used to it.

Ry Cooder:

Nor is the audience quite in a position to totally relate to that, and if there’s anything between you and the audience like that’s an obstacle, you’ve got a problem, you really don’t want to do that. It’s hard to present something like that. On the other hand, ideally, I would like to put together a band that was personnel wise had somebody representing something, I mean that they had brought something in. I got a guy play at home with who’s a Rastafarian guy from down in Jamaica, he’s a percussionist. Now, when he plays there’s a quality of rhythm that the guy is able to bring out and very nice for me, I like that. So I like that sound. And I thought the accordion was a great ensemble instrument, I mean, instead of just organ all the time or something or piano, it’s a beautiful sound in there.

Ry Cooder:

I mean, if I could find a guy who could play button accordion, piano, and B3 organ, I mean, it would be perfect. But it’s hard to find such people, and it’s really hard to get people who play the kind of thing you want to hear, that’s why I change. I mean, I have guys I like to play with, but I change, I bring in other folks just to see what’ll happen. So really you end up playing with whoever you end up playing with, and that Mexican thing was hard for me to pull off.

Ry Cooder:

It wasn’t natural in a certain sense too, because I mean, I had to force those guys to do it, they didn’t even believe that we were going to go on the road until I saw the bus pulled up in front of their house in San Antonio and they all and crying, because then they realized they were actually going somewhere. Up to that time, I think they thought it was a joke. I don’t know if they believed it, but soon we were on that bus and traveling and the reality set in, and those guys went into a depression that lasted about two weeks.

Chris Strachwitz:

That’s strange because-

Ry Cooder:

Little hard for them, later on, they came to enjoy it.

Chris Strachwitz:

Because obviously by the time you got to Europe, because I still hear a lot of reports from Europe, they’ll always remember the-

Ry Cooder:

That was killer in Europe.

Chris Strachwitz:

… show with, with the Tex-Mex thing and everything.

Ry Cooder:

For the Europeans, that was what they think America is. you know what I mean? Odd and quite circus-like all jammed together. They can see that as being, because they have a different perspective. And it was very American and it was quite good and the Europeans just went crazy. Plus they like accordions, they don’t have anything against accordions, so it’s a little bit different. And I ran into Clifton over there and he had a chart record in Holland, a top 10 record, a single in French. And I thought to myself, what a miraculous situation, where a guy as good as he is can also have a hit record, which for him is a great experience, who doesn’t want to hit record?

Ry Cooder:

So I thought to my, well, that’s a moment because I mean, if there ever was a powerhouse performer, it’s Clifton Chenier, he’s the best performer I’ve ever seen. That band he’s got, I mean that band kills anything I’ve seen in rock and roll, that’s all there is to it. That is rock and roll without a shadow of a doubt. I mean that’s the real thing there, but of course and not enough people know that, I mean that’s not their fault. Radio keeps people from hearing things, it limits public access, commercial big radio stations rather than creates public access. So that’s a problem that we are really afflicted with in this country. Not so much in Europe.

Chris Strachwitz:

Of course, part of the problem is the fact that he has recorded for small labels like mine. And, we just can’t get those records around the way a major one could.

Ry Cooder:

Well, a major one wouldn’t want him anyhow, because they wouldn’t see him as being categorically correct. He’s an oddity as far, but that’s the funny thing about Europe, they don’t see it that way there, he’s just him, whatever label he is on he’s liked, he’s good.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well maybe you get energetic one time and try one more as one of those- so you don’t have to to go overseas.

Ry Cooder:

I have to get an idea, I’ve been finding that the music is the thing that has to be right. I mean whoever you get, whether it’s a Ubangi flute player or whatever, so long as the record sounds right to folks. And, to go around saying, “I am now going to go on the road with a steel drum player and a nose flute player, and I’m taking this guy from Japan who plays koto.” I mean that’s not the way to go about it. First, make the music that’s the best, that’s correct in whatever context you’re going to do. And then get the people that can play it. And then you just show up, and you know what I mean? I’m saying? Just to simplify matters, that’s all. Now the Tex-Mex thing was ambitious, but I knew right well that you had to the band and the accordion player, you couldn’t separate them you wouldn’t have the sound, it wouldn’t be right.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. Because of that rhythmic little thing-

Ry Cooder:

They need the rhythm, the rhythm those guys play is beautiful. And when Red, the bass player had to go home for a week, I got my friend, Chris Edwards come out and he’s a Southern bass player, so he plays simple, but it wasn’t quite the same, and it didn’t quite sound and feel the same. And in any case, we recorded that show live and the live record I knew I had to have because no one would ever believe it otherwise. You can talk about things, but people need to know what you’re talking about.

Chris Strachwitz:

Oh, don’t you think it probably came off better that way, because if you had too consciously tried to do this in the studio, you may have all tightened up and that rhythm would’ve been off?

Ry Cooder:

I know. We didn’t get a couple of studio cuts though, after we were familiar with one another and they weren’t scared anymore. I mean, and they realized this did make sense. I’ll tell the classic thing, “Goodnight Irene.” Well, if there ever was a Tex-Mex song, there’s one, but they didn’t know that tune, but I played this tune for them one time and Red said, “We know that song.” I said, “Where’d you hear it?” He says, “No, I don’t mean that, we know how to play that.” And they played it immediately. It was total recognition, was amazing. It was absolutely fantastic. And so we went in the studio the next day, I’m telling you and played it five times, got a balance and recorded, it sounds great.

Chris Strachwitz:

So it goes to show kind of that a lot of good down home musicians have a good ear like you said, for other stuff, and of course, most of them never have the opportunity.

Ry Cooder:

They just don’t have the opportunity, right. So this is what I always have believed that if you show a guy something and you say, “This tune that I know is just like this tune that you know.” And if it’s true, you could be wrong, but if you’re right, it works and it’s there again, it’s like a little explosion takes place, and this new understanding is born, it’s great. And I’ve played with people from Japan, that’s happened. I played with gospel, the gospel singers that I had with me asked me, he said, “What in the world are we doing going out in the road with a Tex-Mex band? I don’t understand.”

Ry Cooder:

They didn’t understand, and Mexicans didn’t understand why they were going to have church singers. I said, “You’ll see it’s right.” And these guys met for the time I’ve been rehearsing them separately, brought them together in San Antonio, and it sounded great from note one. And it was no problem. Of course, for me, that’s fun. And I think it produces good results. And it’s just a matter of can the public ever get to hear it, and I think people like good things, the public’s not stupid.

Chris Strachwitz:

No, I agree. I think we should give them more credit. Well, I mean, sometimes it takes a while for them to know about it, this is why I was hoping that you would do tours like that again. Would you like taking Koto music? And just whatever gets into your head-

Ry Cooder:

I have that in my mind. It depends what comes into your mind.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. You have to be turned on obviously.

Ry Cooder:

I was possessed by that Tex-Mex stuff. I really was intent upon it. But I think that in the future, if I hear a guy, for instance, who’s a hot player and I can use that guy, I’m going to hire that guy, I don’t care where he is from. But there again, you have to be practical, because you can get into trouble. I was so in debt when I finished that tour and in those days that was the seventies, again, the business wasn’t really up for that kind of thing. Nobody cared about that tour. Nobody liked it. I mean the record company didn’t like it, the promoters were scared of it. He said, “What is this? You know, some kind of a trained dog act or something, we want rock and roll here.”

Ry Cooder:

Then when you’d finish the show, “Oh God,” they do a sigh relief, it was all right. But you couldn’t tell them that, “Don’t worry.” They worry about it. So you have to figure your presentation into it and as you say, make a living and be practical, and somehow I heard this, some of this, I was down recently in Louisiana, I heard some of this Creole stuff, Zydeco that is being played down there, twisted up in different ways. There’s some guys down there who are really doing some weird things and it kind of gave me a little bit of an idea, but I got to watch myself because I can’t… It’s okay to take chances, but unfortunately time is a factor too. I mean it’s how much time, I spent three years messing around with Flaco and those guys, when I was through with that, I practically was ready for the hospital. Tell you right now.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, Zydeco may catch you because it’s certainly-

Ry Cooder:

Well, I like Zydeco.

Chris Strachwitz:

And there are some unique bands, maybe you heard that one out of Mamou that has these wild, they’re all brothers, except the father plays accordion, and it’s a family, they’re the wildest rhythm section-

Ry Cooder:

That’s what I’m interested in is that rhythm section, I know who you’re talking about, that’s what caught my attention. To me rhythm is a thing, drummers, percussion, get behind a good rhythm section and I’m going to go down and see those guys, because that could be something. What’s the name of that band?

Chris Strachwitz:

I’m just trying to think of them, I’ve seen them and I can’t think of their-

Ry Cooder:

Is it the Lawtell Playboys?

Chris Strachwitz:

No.

Ry Cooder:

No. It’s a family, you’re right.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. The father’s name is the band. It’s a French name, but I can’t place it right now. But when you were in Louisiana, I also want to like to get into your film work because you’ve obviously been a real agent there for film companies who have a tendency to not to know how to use the real music in films. And when did you start working?

Ry Cooder:

Well, I had done a lot of work in film music, but recently I did this long writer’s thing, but that’s because you see the director Walter Hill, he’s a very smart guy and he knows that he needs the resonance, musically is very resonant. When you have locality, when you want to bring out something of a place, you see, that you don’t hire an 80 piece orchestra that you hire… You find a way to integrate this thing and you’ve got a better, deeper visual situation in the end. And a guy like that is rare, but fun to work for. So we did this thing and he said I don’t want a country music score, this is not country, it’s like the Missouri, it’s the Midwest, it’s this time and in place and all.

Ry Cooder:

And I thought I knew what he was talking about, and so we went ahead and tried to put something together that might sound like that, God knows what that stuff actually sounded like, but it’s open to discussion. And so we end up with like Chinese dulcimer and banjos and fiddles and some Turkish instruments that seem to sound right, just to create an idiom that looks good on screen. Because, if you don’t have 80 pieces, you still got to fill up that great big screen, it’s got to look big. And, I’m doing another picture for him that’s set in Cajun country, and that’s why I went down to see Marc Savoy and some of these guys, start in doing some of that and those instruments that they do and that whole style is flexible and could lend itself to some, to be bent a certain way and put on film. And I think it’s probably going to be a nice one.

Ry Cooder:

I’m also going to do this Jack Nicholson film that they’ve done, which is about border patrol situation down in El Paso with the wetbacks and everything. So naturally one of the foundations, the sound building blocks of this is going to be is accordion music, that’s there as a source, it’s in the air all the time, as well as whatever else I can think of. [Tape pauses.]

Chris Strachwitz:

Marc and those Cajun-

Ry Cooder:

Okay, that’s called a Southern Comfort is their working title. Now, whether or not they maintain that title, I don’t know sometimes things change, but there’s filming it now. And we did some prerecorded stuff for a party scene where they needed the music to get people to dance in time, you know what I mean? So I went down there and got Marc and Dewey Balfa and Frank Savoy got in there a little studio in Shreveport. Funniest thing they said, one of them the guitar players said, “I’ve never been north before.” Shreveport it was Arkansas as far as he’s concerned.

Ry Cooder:

So we had a real good time spend a day in there just doing some different kind of typical stuff and it really was good, and that music there again, records good, to set up some room mics, and the guy had an eight track Ampex machine recorded straight onto the tape, no board or anything, and it was really nice and they enjoyed it. And of course, if I have a job there, that’s to make sure that it’s to interpret what I think the director wants. He wants this and he wants that and he wants things to choose from and play with, and he’s interested in a certain energy that he knows his music has and how to bring it forward how to get these guys to put out.

Ry Cooder:

And so I think that’s something I can do is to try to explain, or to impart to the players, what the application of this is. We’re not just playing tunes here, we need to provide something that will make the work. And so explain that and get them interested in it, and it came off and it sounds really good on tape, Jesus, great sound on tape. And the directors were happy. So later when the film is done, I’ll go back and get them together, and we’ll look at the film and play some more things. And I’ll sort of put together some stuff. But Savoy is a fabulous accordion player, God, I didn’t realize how good he was. He really got into it and he play some stuff, man. It was nice. They had fun, which is the main thing, if you can get people to have fun, you get better playing and the music will come out better.

Chris Strachwitz:

And don’t you think even a commercial film, that’s geared to obviously a mass audience that they will enjoy that kind of thing. You got the guts and-

Ry Cooder:

It has to have that it has to have the guts. That’s what it needs, it needs to be real. And it needs to be strong and very much in your face, you know what I mean? So it carries a lot of weight. Then you see this story, there’s a point in the story where this guy, this army trainee has been through hell, this weird scene, and he comes out clearing in this swamp and he finds these people, having a party. And all of a sudden, here’s this really lively frantic sort of… That kind of two beat thing that they play, that’s like one, two, one, two, one, two, one, two it’s really up. And I mean, they got him to be in the film apparently and it should be good, and it will register with the audience will feel like that’s really happening.

Ry Cooder:

That’s what it’s all about. I mean, if you get studio guys in LA to do this, it won’t work, it will look like nothing. Which has been for years and years, a convenience, people did not want to mess around with this, they wanted guys to write it out, formalize it, read it, play it, go home, get your scale and go home. And, we know what that sounds like. I mean, it’s the same old tricky stuff, film after film. So I’m encouraged to know the people now, some handful of guys who make these films and who want to take advantage edge of locality and setting, are also very aware.

Ry Cooder:

I mean, Walter Hill, he had Nathan Abshire in a film one time. I mean, he knows enough to know these things, and he’s very aware of what music’s all- they’re not very many people like that, but it sure makes it fun for me because it’s a nice job. I get to do everything I like, I got an excuse to go see these guys, I got an excuse to be in the studio and work and be well paid, I might even say.

Chris Strachwitz:

Is Walter Hill also the producer of this border movie?

Ry Cooder:

He’s not the producer. The border thing is a universal picture, Tony Richardson is the English director and Jack Nicholson is the main character. And he plays this border patrolman as sort of a Zen character that he usually does, I’m not here kind of a guy. And, watches this corrupt thing of alien smuggling, and then the border guys are in on it. And it’s true to life, very grim, awful kind of story, Jesus, it’s depressing really, but very factual. I haven’t seen the completed film, I think it’s probably done editing now, but as soon as I get off this tour, I got to go straight to work on it.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, don’t you think that if they really put some good music in there, that that might-

Ry Cooder:

It’ll make –

Chris Strachwitz:

– really make the film?

Ry Cooder:

Color it up. I mean, that’s my job. That’s why they hire me, obviously, is to be able to deal with these things in a way that a conventional sort of written score would not be able to get across, because I don’t write this stuff out. I mean I sit and talk to players, and then I get ideas and I show them, and then we look at the film on a video screen. And that’s a shock for musicians, because when they see what they’ve got to do goes with that picture in a beautiful way, they get happy.

Ry Cooder:

And then they have a whole new dimension, you see, and they have a whole new understanding of really what they’re doing. And if you can see, “You didn’t know this, but this works.” “Oh, I see what you mean.” I remember the first time that happened to me, it was a tremendous revelation. A guy said, “Play this. It’ll look good.” And I said, “Okay.” And I did. And wow, fun. Musicians are oftentimes visually not oriented. They sit and they play and they sing, but to think about images and music together, that’s to me the greatest thing of all, because one reinforces the other. Pretty interesting.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. So your immediate plans are probably to spend a little bit more time for the filmmakers or do you-

Ry Cooder:

Well, I have these two scores to do back to back. I do one and then as soon as I do that one, I start on this other one. And that’s going to take me up until about July. And when I’m done with that, I got to start making another album for myself. That’s busy. It’s nice to be working, I’ll say that though. There were times in the ’70s when nobody cared and the phone never rang. So it’s all very good as far as I’m concerned, because that’s how you learn things and that’s how you get better at what you’re supposed to know, is by actually trying to do it, yeah, taking a shot at something.

Chris Strachwitz:

And this is why I found a lot of times the old timers that I run into, those who kept playing, who are active, they’re so much better than the guys who had quit.

Ry Cooder:

Right. Without a doubt. Yeah sure, because they kept somehow developing and that’s what it really amounts to, you know.

Chris Strachwitz:

Although there’s a peculiar thing the other way, for example, a guy like John Hurt or like Black Ace too, they quit, but then when you got them to play again, they played identically –

Ry Cooder:

I know.

Chris Strachwitz:

– the same stuff they did 40 years ago.

Ry Cooder:

Yes, very strange.

Chris Strachwitz:

Like they were frozen.

Ry Cooder:

Well, it’s like they had an idea. They had one idea and that’s what they did. They heard it that way and they would never hear it a different way. Now there is that. That’s interesting.

Chris Strachwitz:

Because most of the people, New Orleans bands, they kept changing, obviously. The George Lewis band in the ’40s and ’50s didn’t sound like the Sam Morgan band in the ’20s because the rhythm, I think, changed a lot.

Ry Cooder:

I think it’s because of the life around them is changing and they’re responding to it. John Hurt is like a guy in a time capsule. His music represents just him, you see. It’s not the music of the community. The music of the community later on became something else entirely. As you know, you go to rural South now, you go down there, what do you hear? Disco music. But John Hurt is like a guy in a bubble. He didn’t hear all that happening. He just heard himself. And even when he was not playing, he still probably heard the same, ding, ding, ding, ding.

Chris Strachwitz:

It’s really a nice sound.

Ry Cooder:

Yeah, it’s great.

Chris Strachwitz:

It’s great to have that kind of … I’m glad they’re both kinds of –

Ry Cooder:

Sure. Oh, absolutely.

Chris Strachwitz:

… people and even the time capsule types.

Ry Cooder:

Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, perhaps by July after going through all these musical scores, you will probably be turned onto something and making –

Ry Cooder:

Well, I’ll learn or something, believe me. I mean, I expect to have a pretty good time doing these things because I’ll try whatever comes into my mind. I mean, this is an excuse to do a lot of stuff I wouldn’t normally do on records and film thing, really.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah, I think obviously that’s the way. I’m glad you’re working that way, that things that turn you on. I mean I watch Les Blank, the filmmaker, and when something didn’t turn him on, he just simply couldn’t produce –

Ry Cooder:

Couldn’t make.

Chris Strachwitz:

And I’m sure a musician like you is the same way.

Ry Cooder:

Oh yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

That you’ve got to be inspired to –

Ry Cooder:

You got to be motivated.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah, you got to be motivated to come up with something good. I read reviews I guess saying that you didn’t really care for this new record all that much.

Ry Cooder:

Well, the record is good. I just was probably referring to the digital tape machine. I love the music on the record, but I mean this is a thing that’s bothered me for years is how to best record this stuff, what mode to use, what kind of equipment to use. Because I don’t like solid state and I don’t like that transistor sound. And it turns out that the digital machine is so extremely unharmonic. It’s got no kind of harmonic overtones to it at all.

Chris Strachwitz:

It’s too clean.

Ry Cooder:

Well, it’s a computer. How can a computer that translates sound into a combination of zeros and ones have any harmonic overtones? It can’t. It literally takes them away like an eraser. It erases your beautiful third and your fourth interval that a tube has. You know what I’m saying? That’s the thing that nobody mentioned to me. “Thank you very much,” I said. I made two records, and life blood goes into this thing and then I suddenly began to hear this and say, “What is wrong with this record?” Tubes is the way.

Chris Strachwitz:

I’m curious about one thing. I don’t know music, I can’t play or anything, but in Tex-Mex, that music has sort of a lilting, what I call real swing.

Ry Cooder:

Real swing, yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

It’s a real flowing thing. On this new record, to me the rhythm you have is a very different kind of thing. It’s a –

Ry Cooder:

Well, most of it’s … what?

Chris Strachwitz:

I don’t know how to describe it. It just doesn’t flow though. It’s a very jerky type of rhythm.

Ry Cooder:

Well, some of this stuff is very jerky because of some of those things I was trying to do are not conventionally what you call swing, you see. But I hear certain things swing, when they get very stiff they swing to me too. There’s this kind of Okinawan music that I like that swings that’s very, very stiff. And if you do it well enough, if you do it right … and also it’s a question of how you break up the bar. I mean, where the bass drum is, where the snare is. And I like things that way too. I mean it’s just … you see, making these records is experimental, pretty much. You go in there and you say, “I want to hear a certain thing. You guys, help me out. Let’s play this a certain way and see what happens.”

Ry Cooder:

Tex-Mex has a dance beat. That’s the thing to remember, Tex-Mex is heavy after beat and ching, ching, ching, one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four. It’s a dance beat, two step. And that’s what swing is. It’s this two step dance beat. It’s either that or it’s always heavy after beats, see. What the people in the Caribbean do is they place all the emphasis on the front beat, one, do, do, doom, do, do, boom. And they get a reverse kind of swing that way. And it’s very tricky, but for me, I like it that way because I can play off that on the guitar. It’s hard for me to play after beat music all the time because it’s not syncopated. You see what I’m saying? All the syncopation comes to me from the heavy emphasis on one. So I’m fooling around with that all the time. And that’s what the reggae stuff is all about.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. I was going to say it sounds –

Ry Cooder:

Yeah. So that’s the difference. There’s two ways of going about how you produce syncopation or swing, you see. And getting people who can play that with me is one of the main objectives, who can make this kind of a sound. I always end up, at the end of an album project, then knowing exactly how to do it. Well, what are you going to do, turn around and record the record again? You do the best you can. You make it one time, you say, “Okay, this is the best I could do.” And I think that this new record, I think that the stuff we set out to do that I wanted to hear, I got from the players. It’s the best ensemble I’ve had for taking some pretty crazy notions that I fed these guys and making it sound good.

Ry Cooder:

I’m only sorry that the digital machine was what was used and the transistor board was what was used, because I’m never going to do that again. And that’s a subtle, sort of subliminal kind of a sound quality that I don’t particularly like. I don’t think that the listener is going to rush home with their album and say, “Gee, I don’t like the high end on this record.” You know what I mean. No, of course not. But people feel sound a certain way, and for me the studio, that’s the place you do these things so it’s got to be right. And I get all hung up in that, but I don’t think that it … I mean, folks love that digital sound. They went around saying, “Gee, it’s clear, it’s bright.” I said, “Yes, maybe it’s a little bit too clear and too bright.” They say, “What are you talking about?” And that’s a whole other frame of reference that –

Chris Strachwitz:

Except European studios, it seems like to me in the past have always been recording very bright and very clean.

Ry Cooder:

Oh yeah, that’s right. Very clean. They like that sound.

Chris Strachwitz:

I don’t know how they do it, but –

Ry Cooder:

Well, they do it with high tech equipment, you know what I mean? Like all of those … I saw a German remote truck one time. It’s a Telefunken truck in … this was in Hamburg. We had Flaco and them over there and they recorded the show. And I went out to see the truck. Here came the engineers on the truck were wearing surgical masks and gloves and they wouldn’t let me come on the truck. I said, “I’m going to come in that goddamn truck and look at this stuff. I’m interested. Come on. I’m the artist. I’m the guy here.” Well you know what they did? They took an air hose, it’s the kind of thing that they … it’s like a vacuum hose that they used to clean off the equipment. And they dusted me with this damn hose before they let me come in the Telefunken truck and they were really mad. They said, “We don’t want this guy with his grimey hands coming in and being near our equipment.” And these guys had surgical masks on. It was unbelievable, but that’s that concept, recording as a scalpel kind of, forceps. I mean it’s surgical-

Chris Strachwitz:

Music could actually be put on tape that way-

Ry Cooder:

Well, it’s how you view the world.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah.

Ry Cooder:

I mean, and then the guy, what’s his name, Gutiérrez down there in –

Chris Strachwitz:

Salomé. DLB Records.

Ry Cooder:

Had beer all over the lathe and chickens wandering in and out. And that’s how that stuff sounds.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah.

Ry Cooder:

So it’s just way of life, really, is what you’re hearing.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, I hope your next one will be a little gutsier than the … be nice to have –

Ry Cooder:

Well, you as a guy who makes records are reacting to that when you say that. See, I know that’s what it is. And I think that if I’d have recorded this stuff on tube equipment like the music is meant to be, that music is of that nature, it would’ve sounded a lot fatter, but I can’t. What can I say?

Chris Strachwitz:

I think it’d be interesting if you kept this idea of putting in some of these zydeco rhythm bands and mixing with the Caribbean guys.

Ry Cooder:

Well, I think that would work. It’s very close.

Chris Strachwitz:

I think that would make a very intriguing record.

Ry Cooder:

It’s very close.

Chris Strachwitz:

And I think they would probably dig each other in a way.

Ry Cooder:

Oh, of course they would. Yeah, sure.

Chris Strachwitz:

It’d be really amazing.

Ry Cooder:

And then it’s up to the people. I mean, if you get people who are outgoing and extroverted in that way, then they will respond. That’s another thing. I mean, Flaco is somewhat that way so he liked me well enough. A guy like those Los Alegres guys, they could care less. You know what I’m saying? If you present them with a situation like that, what do they care?

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, I think they would. They might be a little bit more standoffish for a while until they get to know you because they’ve been doing their thing. It’s just like somewhere like Ernest Tubb, what we do with him.

Ry Cooder:

Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

He’s been doing his thing for 50 years.

Ry Cooder:

Forever, right. That’s partly true, yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

And I think it would take him a longer time to … but somebody like Earl Hines after all, –

Ry Cooder:

Sure.

Chris Strachwitz:

– he’s been doing his thing for so long.

Ry Cooder:

Forever, man.

Chris Strachwitz:

But I think –

Ry Cooder:

60 years.

Chris Strachwitz:

But I’m sure it was a great experience for him too, because hearing him in concerts, in spite of the fact that most people know him as a genius performer, I think he has still some inferiority complex that he –

Ry Cooder:

Well, he’s a humble man.

Chris Strachwitz:

Maybe he’s very humble.

Ry Cooder:

He is very humble.

Chris Strachwitz:

He feels an orchestra is what brings –

Ry Cooder:

I know.

Chris Strachwitz:

– what we should have.

Ry Cooder:

I know. He’s got a strange idea. I said, “Earl, why don’t you sing more?” “Oh, I can’t sing.” I said, “If somebody told you that you can’t sing, they’re wrong. You sing great.” “You think so?” I said, “Yes. How come you don’t play more piano solo material in your performance?” He says, “Well, that’s that band. They like that band.” I said, “They like you, man. You’re the thing they came to see.” “You think so?” So that’s the thing of a guy has a very … you won’t say naive because he’s far from that, but he is not self-possessed in that way. He’s a conduit as far as he’s concerned, which is great. That’s not the musician as God, that’s the musician as a member of the community and a guy who has this other thing that he does. Some people do this and some people do that and some people play instruments.

Ry Cooder:

So what is unfortunate is when musicians get to be so highly regarded, it is just to take it out of that realm, I think really. Because if you told Earl Hines, “You’re the greatest thing that ever walked, Earl. I’m telling you, you’re the most fantastic,” he wouldn’t understand what you’re talking about. “No,” he’d say, “That isn’t so,” but I mean a true expression of his talent is just you say, “I love this song where you do this.” You make this little passage and he’ll say, “Yeah, that’s great,” because he appreciates what that is, not that he did it. You know what I’m saying? Because I mean, nobody who’s got any brains loves every note they play. I certainly don’t. You got to know that you’re just fallible and sometimes good and sometimes it’s junk. I mean the thing is, like Dizzy Gillespie said, “It’s the instrument. It’s not you. The instrument is the boss and you work at it.” People say, “You’re the master of this style or that style.” I mean, what a bunch of crap.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well obviously a lot of people get put into that because it’s a certain style that catches the public’s ear.

Ry Cooder:

Oh, sure. That’s true.

Chris Strachwitz:

I mean, Jimmy Reed is probably the most extreme for me. He had that one sound.

Ry Cooder:

The one thing that he did, yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

And that’s what everybody loved.

Ry Cooder:

Oh, sure.

Chris Strachwitz:

I think in his case it probably worked because I don’t think he was that open a person who would’ve brought in a lot of other sounds.

Ry Cooder:

No, he heard it that way.

Chris Strachwitz:

He heard things that way and he was lucky, I think, to be able to make a living off of that. But then somebody like Flaco, who’s lived in his thing, but yet he’s obviously open, just like Clifton is.

Ry Cooder:

He is, yeah. Flaco’s very open. Flaco’s very smart, but his ears are good. I mean he knows that he hears things a certain way, and I think it’s people. It gets down to the individual, really. No matter who they are or what they do, it’s the difference between folks, generally speaking.

Chris Strachwitz:

I’d better not hang you up. You want to –

Ry Cooder:

We should go eat.

Chris Strachwitz:

You want to go eat?

Ry Cooder:

Yeah.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. Okay. Let’s do that.