In a Mexico Groove: LA Times article

In a Mexico Groove

Arhoolie Records’ owner will share his vast collection via a UCLA project.

L.A. Times, Februrary 1, 2005

By Agustin Gurza, Times Staff Writer

Chris Strachwitz, an avid music explorer, felt like a visitor in a foreign world when he started collecting Mexican records half a century ago. He had no music catalogs to guide him. No sales charts or trade journals to consult in an industry at times as transient as its migrant customers. Plus, he was a German immigrant and didn’t speak Spanish.

But Strachwitz had an ear for the grass-roots music he discovered in America – Cajun, country, gospel and the blues. And he heard a common quality in those rustic sounds of society’s dispossessed, no matter what the language.

“The first time I ever heard Mexican music was on a small station in Santa Paula, and I just loved it,” says Strachwitz, owner of the respected folk music label Arhoolie Records. “God, it had this sound, and the way these two voices blended together. To me, that’s the most soulful stuff I’ve heard. I mean, I heard it in blues. I heard it in hillbilly duet singing. It didn’t sound to me all that different.”

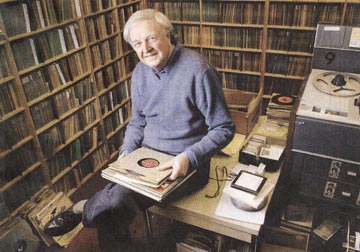

Eventually, Strachwitz, 73, had amassed what is now considered the world’s largest collection of commercially recorded Mexican and Tex-Mex music, more than 100,000 individual performances spanning almost 100 years and numerous styles, from norteñas to boleros and rancheras. Experts say it’s the most comprehensive repository of Mexican vernacular music anywhere, including Mexico.

Soon, the public will be able to access a digital archive of the collection through a special project sponsored by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, in collaboration with New Mexico’s Fund for Folk Culture. With the help of the university’s Digital Library Program, the entire Arhoolie Frontera Collection is being digitally transferred, annotated and archived in the same way the records were gathered – one by one.

Early on, Strachwitz understood the importance of this enduring rural music, not just as entertainment but as an oral account of a marginalized population. In the grooves of the thousands of records in his collection revolves the largely undocumented history of Mexican immigrants over the last century.

The project is being funded primarily by the Los Tigres del Norte Fund at UCLA, named for the famed norteño group based in San Jose. Los Tigres, along with its record label, Fonovisa, established the fund to promote the study of the genre, historically disdained or dismissed on both sides of the border.

By this summer, the public will have Internet access to the first phase of the project, all 16,000 78 rpm recordings from the first half of the 20th century. Each file includes a snippet of the song, an image of the record label and information about the record’s creators, content and condition.

So far, more than three-fourths of the digitized 78s are accessible at digital.library.ucla.edu/frontera. Still to come in the painstaking transfer process, depending on future financing, are Arhoolie’s stockpile of 14,000 45s and 3,000 long plays, covering the 1950s through the 1990s.

The collection contains rare recordings by major artists, such as legendary duo Los Alegres de Teran, Chicano music pioneer Lalo Guerrero, San Antonio accordion ace Santiago Jimenez and his son, Flaco, known for recent collaborations with guitarist Ry Cooder.

One of the most important items is one of the oldest.

The 1928 recording of “El Contrabando de El Paso” (The El Paso Contraband), a Texas tale about liquor smuggling during Prohibition, is considered one of the world’s first narcocorridos, a precursor to the border ballads about drug trafficking that would become so popular half a century later. Although the song has been recorded dozens of times over the years, experts say the composer had never been identified – until now.

True to the tune’s first-person narrative, the man who wrote it appears to have been the man who lived it.

Last year, UCLA Spanish professor Guillermo Hernandez, author of an upcoming book about corridos, traced the events that inspired the song, which tells the story of a group of smugglers being taken by train from El Paso to the federal prison at Leavenworth, Kan.

Old prison records identify one of the convicts as Gabriel Jara, caught with 90 gallons of illegal brew in the early 1920s. Hernandez knew he had found his man when he discovered in the archives that the 28-year-old Jara had written several letters to Leonardo Sifuentes, a resident of Ciudad Juarez.

The prisoner’s pen pal, as it turns out, happens to be half of the singing duo of Hernandez & Sifuentes, who made that historic recording. Professor Hernandez, no relation, believes the convict was transmitting his verses through the U.S. mail.

The discovery won’t change history or make anybody rich. But it shows that in this type of Mexican music, art doesn’t imitate life – it documents it.

As former head of the Chicano Studies Resource Center, Hernandez was instrumental in bringing the Arhoolie collection to UCLA. He was a graduate student at UC Berkeley in the 1970s when he first met Strachwitz and got engrossed in his collection.

Strangely, Strachwitz says roots music was largely missing from his own rural boyhood in what is now Poland, where country folk “listened to Nazi music, mostly marches, and pop music which was horribly schmaltzy.”

Strachwitz was just 16 when his family came here after World War II. He started collecting records almost as soon as he hit these shores.

He studied math and engineering at Pomona College and UC Berkeley, then briefly taught German in high school. In 1960, he founded his own label to capture the folk music that so fascinated him (www.arhoolie.com).

Mexican country music has provided the soundtrack to rural life since the Mexican Revolution of 1910, which sparked the first big waves of immigration. But most of the early recordings were made in the States, not in Mexico, says Strachwitz.

There was no market for the music in its homeland, he explains, because Mexican peasants earned too little to afford records, even if their homes had electricity to play them.

On the U.S. side, however, major record labels catered to an immigrant workforce earning dollars. Evidence of their growing buying power can be found in customs documents which show that the most common items being taken back to Mexico are records and record players acquired here, according to research conducted by Hernandez, the UCLA professor.

During World War II, a shortage of shellac forced U.S. labels to concentrate on American pop music, says Strachwitz. Mexican labels started taking up the slack in the late ’40s, once they realized the market’s potential.

In considering the fate of his collection, Strachwitz wanted to make sure the music wasn’t just stored in a corner, even in some place as prestigious as UCLA. He knew of other bequeathed collections that “simply go into a dark hole someplace and they’ll never be heard again.”

UCLA’s Digital Library Program was a high-tech way to keep the music alive.

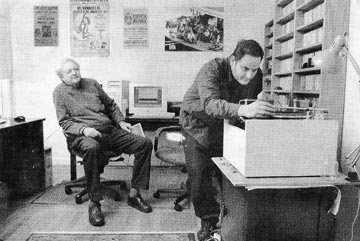

The work is being done at Arhoolie’s El Cerrito, Calif., headquarters by Antonio Cuellar, a paid employee who listens to each song as it’s being digitized. Cuellar, who plays in a Latino punk-rock band, keeps a running index of various themes contained in each lyric – “Love, unrequited,” “Boasting, sexual,” “Execution, firing squad,” “Strikes and lockouts,” “Murder at dance or celebration” and “Tragic triangle.”

Many of the old corridos, including “El Contrabando de El Paso,” were so long they were recorded in two parts, one on each side. Over the years, Strachwitz picked up every two-part corrido he could get his hands on.

Many of those original versions contain lost verses. Even Los Tigres, says Strachwitz, were surprised to discover in his collection a two-part rendition of “El Huérfano” (The Orphan), recorded 50 years ago on the Okeh label in San Antonio.

“They were just amazed that there were so many more verses than they had heard,” says Strachwitz. “Nobody had ever seen these old records, and they finally began to realize that all this music had been documented since the beginning of the last century. So they were really impressed.”

A collection for the ages

Title: “Ezequiel Rodriguez”

Artist: Ortiz y Maldonado con el Dueto Abrego

Label: Orfeo

This corrido, or narrative ballad, is one of the earliest recordings featuring two artists who would later become the famous duo Los Alegres de Teran, the first superstar group in Mexican regional music. The duo was composed of Tomas Ortiz, on the 12-string guitar known as bajo sexto, and Eugenio Abrego, who’s backup accordion on this record. Their big hits from the ’50s are on the Falcon label, based in McAllen, Texas. Their early recordings on the Orfeo label, based in Monterrey, Mexico, are very rare.

Title: “El Contrabando de El Paso” (El Paso Contraband)

Artist: Luis Hernandez-Leonardo Sifuentes

Label: Victor

Recorded in 1928, this corrido about booze-smuggling during Prohibition is considered an early precursor to the narcocorrido, the drug-smuggling ballads that became widely popular in the 1970s. This 78 rpm is the original version of a song that has since been recorded dozens of times, though later versions use the Spanish contraction “del Paso.” It was recorded in the Texas border town by the New Jersey-based Victor label, which did field recordings in hotel rooms.

Title: “Amor del Bueno”

Artist: Miguel Aceves Mejia Label: Peerless

Aceves Mejia was one of the great mariachi singers of all time, famous for his thrilling falsettos. But he started his career singing tropical music. In this famous bolero, written by Abel Dominguez, he’s backed by the orchestra of Noe Fajardo on Peerless, one of the major Mexican music labels. The record illustrates the breadth of styles included in the Arhoolie collection.