Fred McDowell Interview

In 1964 Chris Strachwitz went to Como, Mississippi to record Fred McDowell for his record label Arhoolie Records. In this interview, Chris talks about his memories of going to Mississippi, meeting and recording Fred, going to a house party (see photos below), the Rolling Stones, and how things were back then.

- Chris talks about Fred McDowell 00:00

Interviewee: Chris Strachwitz

Interviewer: Tom Diamant

Date: Feb 5th, 2020

Location: Berkeley, CA

Language: English

This is an interview originally recorded for research purposes. It is presented here in its raw state, unedited except to remove some irrelevant sections and blank spaces. All rights to the interview are reserved by the Arhoolie Foundation. Please do not use anything from this website without permission. info@arhoolie.org

See below photo gallery for a transcript of the interview

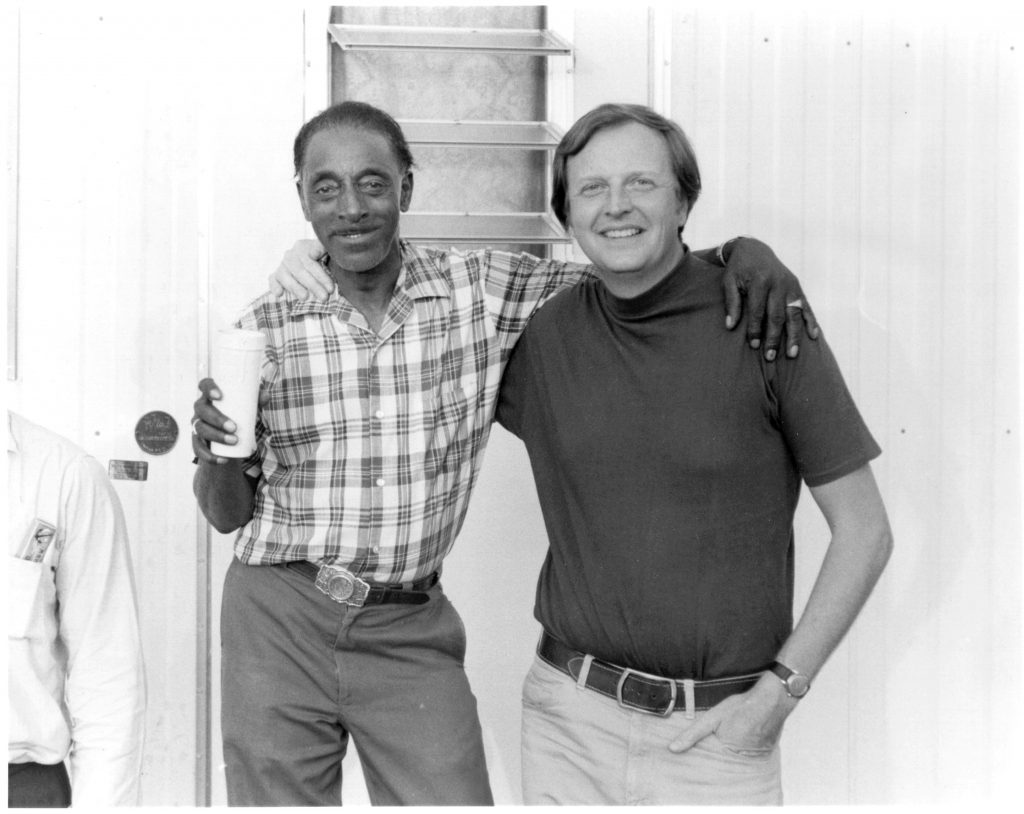

All photos in the gallery by Chris Strachwitz, except for the one of Fred and Chris which was taken on Chris’ camera, possibly by Fred’s wife, Annie Mea McDowell

Chris Strachwitz Interview Transcript:

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, I first met Fred McDowell’s music orally on a fantastic Atlantic LP that was done by Alan Lomax, I think the previous year, when he took an amazing tour through the South with Shirley Collins, and happened to encounter Fred McDowell in Mississippi.

To me, that was the most interesting, exciting musician I had ever heard in my life, especially that song called, I’m Going To Write Me a Few of Your Lines, whatever it was, God how can I forget that tune. And it was just an absolute classic.

Chris Strachwitz:

So I wrote to Alan Lomax and said, “Would you mind sharing the address with me of Fred McDowell?” And he wrote back and said, “Yes, he lives in Como, Mississippi.” And he told me his address, which was PO Box, no, it was box something, route something, in Como, Mississippi. And so when I got to Como that winter evening, afternoon, whatever it was, I went to the post office and asked “Where is route this and that, and box so-and-so?” “Well, you go up”, I think it was, “highway 51” or whatever it was, 61, I’m not sure if I remember. “And then you take the second or third street to the left that goes out into the country, and his farm, where he works, will be the second one or the first one, right on your right.” And sure enough, I drove into this yard of this farm and there he was getting off a tractor.

Chris Strachwitz:

And of course, I recognized him from his photo on the Lomax LP, which had it prominently on the front in color even. And of course, I said, “Are you Fred McDowell?” He said, “Yes, sir.” And I started telling him how wonderful I found his music. And he was just this kind guy, right from the start. And I had driven down there from Houston where I had actually, on that same trip, I’d met Clifton Chenier for the first time, hanging out with Lightning Hopkins, because we were waiting for Horst Lippmann to come in from Germany, to meet about going overseas and so on. And I brought with me my tape recorder in my trunk. I had driven all the way down to Houston, and figured Mississippi ain’t that far. So I stopped by Fred McDowell’s place. And if you ever met him, he was such a wonderful guy, who was just in love with his own music, and loved singing and performing, playing for people, really. Not performing necessarily, but just the way he was.

Chris Strachwitz:

And so we made that record the first night I was there. And I think I even stayed in his house, that’s right. He had a little small house, and he gave me their bedroom, and he and his wife slept on the couch in the living room. I mean … And I’ll never forget the breakfast he made. It was some eggs, and we had syrup, like from sugar beets, that kind of syrup with our bread, white bread of course, as people always ate in the South. And I always remember that so strongly.

Chris Strachwitz:

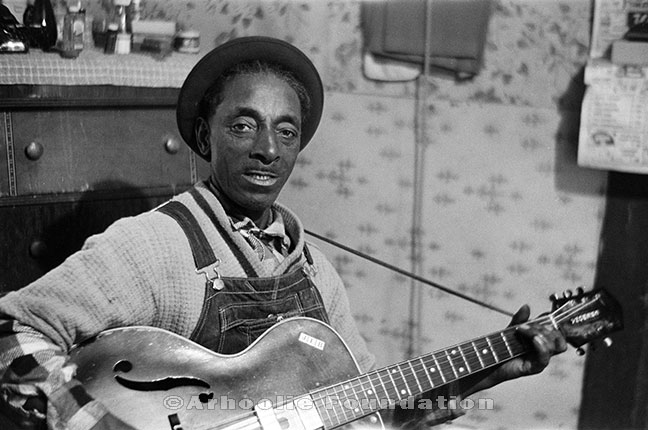

And God, he just started. I was lucky. By that time, I had a pretty good condenser microphone. It was an omnidirectional one. But he was a strong singer, so I had no problem picking him up and his guitar. It was a wonderful balance I thought. There was no amp involved, and he just sang one song after another. I forgot if I brought any little whiskey with me in the car or not, because I knew Mississippi was dry. I may have done that, but I don’t recall. And I took that picture that I used for the cover of that. I’m not sure if I used it on the first. But I was just totally enamored by his music and his personality too.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah, that’s the picture I took on the original Mississippi Delta Blues by Fred McDowell. And there was a purple cover and Wayne Pope designed that. That was probably put out the next year, probably early, I think, after I recorded it in you say in ’64 I recorded it. Yeah. Was it early in ’64? I know it was winter time.

Tom Diamant:

Yes. It says February 13th, 1964.

Chris Strachwitz:

Really? February 13th, well that’s coming up.

Tom Diamant:

In Como, Mississippi.

Chris Strachwitz:

In Como, Mississippi, at the farm. I don’t remember the owner’s name, you know?

Tom Diamant:

…condenser microphone.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. And he had his own guitar. I think I also … I’m not sure if I carried one with me on that trip or not. Thank goodness he had that. Does it show him playing a guitar on that front? No, it doesn’t.

Tom Diamant:

Yeah he has a guitar there.

Chris Strachwitz:

Oh, that must’ve been his, I’m pretty sure that was his.

Tom Diamant:

It says on the back here, that side two tracks one, two and three are played on my bass heavy Gibson.

Chris Strachwitz:

Oh I did bring it. I had a Gibson by that time?

Tom Diamant:

That’s what it says.

Chris Strachwitz:

How weird because what was that thing that we put in a vault?

Tom Diamant:

That’s a Harmony Sovereign.

Chris Strachwitz:

That’s right. That was the first year that I’ve went down that I was in ’60. Maybe by that time I had a fancier one. Who knows? Who knows? I probably didn’t give you details on all those records, but you know, we became good friends and pretty soon it became obviously that he’s going to be a popular blues singer. At that time during the folk music boom they were finally accepting as much of this regional music as the folk music of this country. Not just that Peter, Paul and Mary stuff but also the real stuff out there in the world.

Chris Strachwitz:

And Oh God, we went so many places together. And he was just always in a good mood. I’ve never seen him in a bad mood, and he was just an unusual, totally delightful person. And I visited him many times since then down in Mississippi of course. One of the nicest times when we actually went to Europe for the American Folk Blues festival. It was on the same year that Big Mama Thornton also went over there and Buddy Guy was with us and so on. And that’s where we made a few cuts with Fred backing up Big Mama Thornton. I thought there were some of the nicest stuff. I wish I’d have done more of that.

Chris Strachwitz:

Because they were always playing in the hotel rooms. I would walk in, I forgot. I think it was usually at Fred’s room and they were just so enjoying themselves, and Big Mama would just make up stuff. And which she was too shy to do most of the time, she was not a person who knew a lot of songs. Of course Fred knew and a lot of stuff and not only blues, he knew these spirituals because he played in Como in a little church that he learned, for example, You’ve Got To Move in. And I didn’t particular remember all those lyrics at the time, but later on they really sank in. And of course, and at that time I just thought everything he did was fantastic. But then the Rolling Stones covered that song. It was a long, tedious, drawn out lawsuit we had. I’ve forgotten what year that happened.

Tom Diamant:

I have in my hand here a letter that you wrote on August 19th, 1971 to Mr. Mick Jagger and it starts out, “Dear Mick Jagger, I hope that this letter reaches you personally and is not held up by yet another office or lawyer some place along the line. Although, I have never met you. I suppose we share a great love for blues and the guys who spent their lives singing and playing together.” Tell me the story about the Stones recording You’ve Got to Move.

Chris Strachwitz:

You know, I don’t remember writing that letter, but obviously I did. All I remember is that they did and it was so wonderful of them to put Fred’s name as a composer underneath the title. Most records had the composer in parenthesis, and it said strictly Fred McDowell. Well, all kinds of hell broke loose because I sort of had a vague idea that he didn’t compose that song. He probably heard it in his church and when it all came to a loss … No, it actually started when Manny Greenhill called me out of the blue and said, “You know, Fred McDowell didn’t write that song. Reverend Gary Davis wrote that song.” And I said, “Manny, he was a wonderful manager and a great guy too, Manny Greenhill, he treated his people so well, and he was such an honest guy. I don’t know. He was simply amazing.

Chris Strachwitz:

And so we thought about it and I actually wrote to Fred McDowell immediately asking him, “Where did you learn that song?” He said, “Chris, I learned it out of a little song book that we had in church.” And he said, “Can you see a date in there or anything like that?” “No, I don’t think there is”, “But could you send it to me?” I told him so. He sent it to me and sure enough, it was one of those down-home printing jobs, it didn’t give any credits at all to nobody. And it was obviously a traditional song that really had no composer ever. And there had been other records made of the song by the Two Gospel Keys I think that went on a 78, and I mean there was a number of other people.

Chris Strachwitz:

So I finally talked to Manny again and said, “If either of us could claim this totally, we may not get anything because people will say it’s traditional.” And so if we made a deal together and it said basically that as long as it’s recorded a la Fred McDowell, which is with that slide guitar, really slow but using the slide guitar and just absolutely a very unique sound, then it should be credited three quarters to Fred McDowell and one quarter to Reverend Gary Davis, who picked clear guitar. He was a kind of a picker. And if anybody records, You’ve Got To Move a la Reverend Gary Davis, then he should get his three quarters out of it. And one quarter to Fred McDowell. We all signed that agreement.

Chris Strachwitz:

And of course when the Stones management first heard about this racket that we’re claiming the song, they were furious because they said, “No, all the songs that the Stones recorded were written by them.” And I said, well, how come they put Fred McDowell’s name as composer on that Atlantic, was it actually an Atlantic or ATCO? I think it was on Atlantic. Yeah, that was a definitely on Atlantic label. And so they had to give in on that. I’m not sure which of the Stones actually persuaded the company to put Fred McDowell as a composer. It could have been either Mick Jagger or who was the guitar player of the Stones?

Tom Diamant:

Keith Richards.

Chris Strachwitz:

Keith Richards. Yeah. I think it may have been Keith Richards who told Atlantic who’s the composer of the song. And so we finally, I think it was settled out of court, I believe. I don’t remember going to court over it. And so they agreed to that. And I think it was both because it would have given his management a bad name if they pulled a fast one stealing this black man’s music. So, but anyway, so that was one battle and but then we had so many good times together.

Tom Diamant:

That that was on the Rolling Stones Sticky Fingers album. That’s the one with the Andy Warhol cover with the zipper on it. And which must’ve sold tremendously well. How did Fred react to the royalty check that he got?

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, unfortunately he already knew he had cancer. When I drove down to Mississippi, I think I gave him a check for $12,000 or something like that. He said, “Chris, I sure appreciate them boys liking my music.” And it was a biggest check he’d ever seen in his life. I mean, it was just a good feeling. Although we all got to get out of this world, you can’t get out of it alive, like Hank Williams sang. And I think he knew his time was short by then, but he, I remember he took me, I think on that same … No, I’m not sure where Elsie took me that time. That was one of the last times I think I saw him.

Chris Strachwitz:

But he also once took me on an amazing hunt for … I asked him, who did you learn from early on? And he said, this fellow Eli Green is the one he really learned from. And I’ll never forget that hunt for Eli Green was just unbelievable. He sort of knew in what little town that he supposedly lived in, but we drove to the little town, I don’t remember what it was, and he went into a joint, and he said, “Chris, stay in the car. I’ll be right back.” And he went in there and apparently asked him, the people in there, they knew where Eli Green lived. Well, it’s a place you would have never found in all you’re living life. It was past a field. It was just a dirt road basically. And it ended suddenly where the sort of a forest started. And he said, “Chris, you’ve got to leave your car here. We got to walk into the woods.”

Chris Strachwitz:

And at the same time I didn’t only have my big recorder because I couldn’t have carried it out of there. I also had a funky little Uher recorder, which didn’t work very well, but it did function sometimes with a battery in it. And so I took that along. Plus I think we took either Fred’s … I think we took both Fred’s guitar and I took my guitar too, that I always carried. And we walked into those woods and here was a run down one room, country shack literally in the middle of these woods.

Chris Strachwitz:

And Fred knocked on the door and here comes this man, pretty tall guy, “Ah, what are you guys doing?” He was kind of a wild man almost. He was just living out in the woods by himself. Unbelievable. And he said, “Chris, this is Eli Green.” And all I remember there was one bed in the … I’m not even sure if it had a mattress. I think it had a mattress on it and we sat down on the mattress. And those two guys, we must have taken something to drink, I believe. I’m not positive. Again, they just started playing together and I started recording together immediately because he had a rough voice. It was unbelievable stuff.

Chris Strachwitz:

Is that actually did I issue that on that? I think it’s on the second album, I put the two cuts that survived that because the tape machine ran out after two songs. The speed just gave out. Brooks Run Into the Ocean and oh, that’s on the second volume of Fred McDowell. Yeah, and it was the most … I mean the guy later on, I didn’t even know who Charlie Patton was at that time. I don’t think, I had no idea what he sounded like. This guy sounded more like Charlie Patton, I think if you listen to that record. And he did most of the singing, but they both played guitars and it was just unbelievable.

Chris Strachwitz:

And like we were saying the other day, it was really the meeting all these cultures and meeting the people involved that made it so fascinating. A lot of people go on safaris and they kill poor animals and bring trophies home and all that. I’m glad I turned to a song catcher and just captured this amazing stuff that happened sometimes.

Chris Strachwitz:

It didn’t always happen. And people pretty much I noticed reacted the way they sensed you. Like when I first met Lightning, I think I was probably the first white man he ever met who was simply a fan of his, who didn’t particularly want to record him. I didn’t have that in mind at all. The first time in ’59 when I went to Houston and met Lightning after Sam Charters had sent me a postcard saying, “I’ve found Lightning Hopkins. He lives here in Houston.”

Chris Strachwitz:

And so he invited us to come to this beer joint. And I mean that was another amazing, amazing event. But that was just outside of, it was connected in a way because Lightning became a good friend of mine that way. And I always loved to hang out with him. I had some pretty amazing experiences with him.

Tom Diamant:

You took a series of pictures that looks like a party, a dance party in front of a house with Fred playing. Can you tell me the situation that this took place in?

Chris Strachwitz:

Well, Fred always told me, “Chris, we didn’t use to play. I didn’t, there were no beer joints in that part of Mississippi really. I mean there were some, but for the popular singers, but basically Mississippi was dry. And he said, we’d have house parties and this is definitely, he said, “Come on, we’re going to have a little house party.” I think this was on a Sunday. They just came from church that day. And I don’t recall if I went to the church with them or not, but, and I forgot whose house it was. But yeah, he was sitting there playing his guitar and people started dancing and just having a nice time, that’s the way so much good music is made. It makes me almost cry all the time when I think about this stuff.

Chris Strachwitz:

And I think that was the same day here where he was sitting under the … Oh yeah. They were just all outside all of a sudden. I don’t know how I … Let’s see who that is in the background. Is that a white woman? No, they’re all black folks, I think. Obviously they’re all friends of Fred’s, and yeah, I like this picture actually better than the other one. What do you think?

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah. I like this one a lot. Oh, this is a good one too. I’m glad I took a lot of shots once I started banging away on my Leica. When I saw something good, I didn’t have a movie camera, but I figured, hell, this the is closest thing is I can get to it. Yeah. Oh, that’s really neat. I have no idea about staging them all different, having Fred sit under different trees and stuff. And my memory is fading fast. I’m glad that these pictures exist because I would have never been able to tell you much about it. And that was obviously their car. I didn’t have that kind of a car at the time. Oh God. Yes.

Chris Strachwitz:

And he took me who once to a picnic out in the field where they had one of those fife and drum bands, they were really carrying on. And Fred just loved those parties. He would have just a drum beater and the fife player, that was basically the music. I don’t think he ever played with that group. No, that was just … What was his name? Napoleon Strickland, I think was the flute player. And I think there were some of his kids or somebody had played the drums. Anyway that was out in the field and they were just having a ball. It was this wonderful stuff.

Tom Diamant:

Let me ask you about that. So the fife and drum, which is quite an old style of music was still being played for people’s enjoyment at that time?

Chris Strachwitz:

Yes, that’s right. Yeah. That seems to have been their weekly entertainment on weekends when they had time, they’d either play at house parties, but that would be more for guitar players because, but they also … I’m not sure if they ever played that kind of that fife and drum music indoors because it’s pretty loud and they really bash a bass drum and that flute or fife or whatever you want to call it, is also pretty piercing.

Chris Strachwitz:

No, that’s very … I’m sure Alan Lomax would have thought that was an Afro retention, don’t you think so? It probably is. And yeah, it’s just amazing how strong some of those traditions are. I think it’s still around some of the kids of some of these musicians have carried it on. And if you live out in the country, you see, you kind of retain traditions much more than if you’re in an urban area where you’re subjected to all kinds of other sounds. Out in the country people live much more isolated and they don’t hear that much. Anyway, I never remember any of them listening to the radio or not, or if the radio was on, it would be some … I really don’t remember what they were listening to. I’m sure it was there.

Chris Strachwitz:

Just like in earlier days. Robert Johnson they had heard other kinds of music, but that was one of the reasons I think Robert Johnson apparently was so amazing because he was raised in Memphis in a different class of people. And just like Lonnie Johnson were much more educated in that field. But to me, somebody like Fred McDowell, God they played the most gorgeous music ever. And it came down to him from a guy named Eli Green, and he played in that tradition, obviously, he probably learned from, who knows whom? Who knows how far back that goes. I think there was a story-