Chris Strachwitz Remembers Lightnin’ Hopkins

“So we went over there and there he was just ferociously playing on his electric guitar and singing really powerful stuff, it was just really, really amazing. And shortly after we had come in, he just segued during his singing by pointing his hand at me and singing “Whoa, this man come all the way from California just to hear poor Lightnin’ sing.” Then he went on about this song about how he was aching and his shoulder was hurting him, because his rheumatism was bothering him, and he was just making up this poetry about what was in his head that day, you see? I had never encountered anything like that.” – Chris Strachwitz on first meeting Lightning Hopkins

Chris on meeting Lightnin’ Hopkins

- The Robert Stone Sacred Steel Archive: Elton Noble Interview 00:00

Interviewee: Chris Strachwitz

Interviewer: Tom Diamant

Date: 10/22/2020

Location: On the phone in San Rafael, CA (Strachwitz) and El Cerrito, CA (Diamant)

Language: English

This is an interview originally recorded for research purposes. It is presented here in its raw state, unedited except to remove some irrelevant sections and blank spaces. All rights to the interview are reserved by the Arhoolie Foundation. Please do not use anything from this website without permission. info@arhoolie.org

See below photo gallery for a transcript of the interview

Chris Strachwitz Remembers Lightning Hopkins Interview Transcript:

Chris Strachwitz:

Talking about Lightning Hopkins. Well, he kind of started me off on my whole adventure. But let’s start from the beginning. The summer of 1951 I was in Claremont California (east of Los Angeles) doing a summer session at the Claremont Men’s College. I remember that. And there I would get, in the afternoon, that daily program that Hunter Hancock had on KFVD in Los Angeles called Harlem Matinee, and he was starting to play real down home blues. (I know I heard Fats Domino that summer!) I think I remember hearing Sugar Mama (by Lightning Hopkins). “Where do you get your sugar from? Do you get it from your daddy’s sugar farm?”, or whatever, and then I really remember, “Hello Central, please give me Central 209, I want to talk to my baby, she is way on down the line. Seem like the buses done stopped running, trains don’t allow me to ride no more.” Anyway. That record just really got into my head and never left it for some reason, and I became a total, I guess, really a fan of his music, the way he was very, very different from all the other down home blues singers who were being played at the time by Hunter Hancock.

The others sounded in a way more rhythmical, like Sonny Boy Williamson. I think I heard his first Trumpet Records coming out. Although, I didn’t really know what the labels were until much later. And I heard Dust my Broom by Elmore James, and I think I heard some Muddy Waters, but I’m not sure of all those other ones, because my real stuff that’s really stuck in my head was Lightning Hopkins’ sound. I just thought, “Here’s this amazing guy who obviously just seems to make up stuff”, but again, I didn’t really know that. In contrast to the jazz blues that I was used to, like Trouble in Mind and a lot of the blues that the Dixieland bands would play. Like Dick Oxtot’s band or whatever, and of course the George Lewis band. They were playing blues, but it was very, very different. Here was just this lonesome voice and the guitar. That’s all. And it just captivated me.

So I continued to be a Lightning Hopkins fan, and when I met Sam Charters at Berkeley, you see, about 1956/7 someplace in there, I met him while he was also studying at UC Berkeley, and he was playing in a Dixieland band. But he was also beginning to write his book about the country blues, and he had a trunk full of really old 78s by Blind Lemon and people like that which he had found while he was traveling in the South and getting them from junk stores and so on. But I didn’t really like those. To me they were just too tinny-sounding, and I much preferred the current crop, especially Lightning Hopkins. And I guess, I talked Sam Charters into listening to my Lightning Hopkins records. He was not too impressed at first, but a few years later apparently it did get to him and it must’ve been in 1959 I think when I was beginning to teach high school at Los Gatos and Saratoga High schools that I got a postcard from Sam, and he said, “I found Lightning Hopkins. He lives in Houston Texas.”

And you see, at that time no one really knew where these people were from. I think I saw in some French magazine, or there were these jazz magazines like Jazz Monthly and Jazz Journal in England, and there were really devoted pages to blues, to these kind of blues artists. But even those people didn’t know much of him. The French guys, they didn’t know about Lightning Hopkins. They mentioned it somehow. Anyway. So all of a sudden this light bulb goes off in my head, “Oh my God, this guy actually exists, and I just have to go see him.” And finally in the summer of that year, that’s right, it was in the summer of ’59, I literally took a pilgrimage to Houston. My sister wanted her car driven to Albuquerque, so that got me halfway there, and then I took a bus from there down to Houston where I met the guy who Sam Charters had told me was trying to be Lightning’s manager sort of. And his name was Mack McCormick, and Mack really became an incredibly important person in my life as well, besides Lightning of course.

So when I met McCormick I was staying at the YMCA in Houston, and this was all before air conditioning, but that’s a whole other story. And it was hot as pistols down there, as you can imagine, in the middle of the summer in Houston Texas. But God, I didn’t care. I was young and was totally freaked out by this whole idea of really getting to meet a blues singer that I thought was just fantastic. So Mack said, “Yeah, we can go meet Lightning”, and we did, and he said, “Yeah, we will go to Lightning’s place where he stays on Hadley Street.” So I met Lightning there and I thought he was really a nice person, and he was very nice to me right off. I told him, “I’m just a real fan of yours, and I just couldn’t believe that you actually lived here”, and so on and so forth. Then he said, “Well, come on by tonight, I’m playing over at a little beer joint.” I forgot the exact name of it, but Mack knew where it was.

So we went over there and there he was just ferociously playing on his electric guitar and singing really powerful stuff, it was just really, really amazing. And shortly after we had come in, he just segued during his singing by pointing his hand at me and singing “Whoa, this man come all the way from California just to hear poor Lightning sing.” Then he went on about this song about how he was aching and his shoulder was hurting him, because his rheumatism was bothering him, and he was just making up this poetry about what was in his head that day, you see? I had never encountered anything like that. I’d heard jazz blues-type singers and they knew their songs that had a fixed text and total structure to them. They never changed the lyrics hardly. Well, Lightning I don’t think ever sang anything twice the same way. He was obviously, as I much, much later learned from the amazing book that McCormick and Paul Oliver finally brewed together with the help of Alan Govenar, that this is really the songster tradition in the old days when that kind of performance was really valued by the people.

And that’s why Mance Lipscomb, once we met him, simply called himself a songster. He did not even refer to himself as a blues singer, but he said, “Yes, I do play blues, but I’m a songster.” And I think Lightning really fell into that more traditional category. It was in the 20s when of course blues were widely recorded that that label became sort of a fixated idea that you had to have these blues in a certain way. You couldn’t just walk into the studio like Lightning apparently did all his life and just make up stuff. Anyhow, so I was absolutely fascinated by the guy, and of course I think I was probably the first white guy that he’d met who didn’t particularly say anything about that I wanted to record him, you see. I didn’t mention that at all. That really hadn’t hit me yet. I just thought he made some fantastic records and I didn’t even think about it. So I think he was kind of considering me as a fan rather than a guy who just wants his music and possibly exploit him. And he sort of behaved towards me pretty much in that way as we got to know each other.

Although, when we actually first mentioned the idea of my recording, which was the next year when I came back to Houston (with a tape recorder), he immediately got into an argument with Mack McCormick who said, “Well, first he wants to also make some recordings.” I think that sort of turned him off there briefly and they almost got into a fight over, “How much money that’s going to cost me”, and, “Da, da, da, da, da.” Of course, I didn’t even have a pot to pee in yet and I just wanted to see if I could tape him, because I was trying to capture that sound, but not in a private house, but in a public beer joint like how and where I first heard him. Anyway. It was really, really difficult. So I kept in touch with him, and yeah, I think the next year when I finally came back with a tape recorder in 1960 he was just about on his way to California anyway, because Alan Lomax’s brother John Lomax in Houston, he was hired by Barry Olivier to bring him to the West Coast for the Berkeley Folk Festival.

I think it was going to be his first appearance. I forgot he also had him booked someplace else, but I forgot. Anyway. So this was in 1960. So that’s when Mack and I, since Lightning was almost leaving the next day for California, Mack said, “Oh, Chris, there must be other people like this Lightning that you like.” He was not that fond of him. To him, the only great blues singers were really people like Son House, and I’m not sure if he’d been really dug up yet, but he wanted that real stoic … I don’t know how to describe it. Anyway. He didn’t like Lightning, because Lightning was sort of to him just an entertainer. He was definitely an entertainer, but he knew how to entertain his people. So Mack said, “You know what? You have a car now, so why don’t we go up the country and see if we can’t find some people like Lightning to get you.” And that’s how we eventually met up with Mance Lipscomb. But that’s of course a different story. So I recorded that Mance Lipscomb record in the summer of 1960.

So the next year in ’61 is I think when I got back to Lightning and wanted to try to record him again. That may actually have been the first time. Yeah, I think so too. It wasn’t in 1960 that I tried to record him, or even mentioned it. That happened in 61, and I think I recorded one piece and it was a disaster. First of all, that damn tape recorder was giving me trouble by that time. So then it turned out that we got along pretty good, me and Lightning, and when the Folk Festival in Berkeley, they had Mance and so on, and I forgot exactly, and the Cabal was happening in Berkeley the one that Debbie Green and Rolf Cahn operated. And they were really keen to get Lightning to come out to California. So I somehow started booking him in several places. I think it was the Ash Grove in Los Angeles, because Ed Pearl, he was known to want to present the real folk musicians rather than the Kingston Trio-type of stuff, which was really the big hootenanny toodle-doodle-la-la-la stuff that was called folk music.

So I started booking. I’m not sure if I had to send him money or not. Somehow Lightning came out and I think he stayed with me by that time. This was in 1962 or three by then. I just really enjoyed it too. I had heard about Alan Lomax actually already at the high school that I went to, the Cate School. Mr. Cate was the headmaster at that time when I was there from ’47 to ‘ 51, and he got wind of my interest in vernacular music, especially jazz and blues, and he talked to me about, “Oh, Christian, there was this man who came here to the mesa”, it was on top of a mesa, the school, “And he brought along with him a big black musician, and he sang this song about, ‘Irene Goodnight.'” And I said, “Oh my God, that must’ve been Alan Lomax and Lead Belly.” He said, “Yeah, that was his name, Mr. Lomax who came and brought him.”

So I was very much aware of what he had done, you see, because I’m not sure exactly what year Lomax brought Leadbelly, that I still have to do some research on. Anyway. I was just in paradise kind of. First of all, getting to meet people like Mance a little better, and Lightning especially, because I was really captivated by the whole African-American blues world. To me, that was the most interesting world there was, musically. Although, I loved hillbilly music and I loved New Orleans jazz, but that was also drenched in blues, but again, a different kind. It was the jazz blues. But definitely I’ll never forget when the George Lewis Band recorded “Make Me a Pallet on the Floor” it was sung by this Elmer Talbert, the trumpet player. That was just pure blues. George Lewis also recorded a thing called the “Jerusalem Blues” on his clarinet where he was featured. It’s just pure, pure blues. Blues was very, very popular, even at that time still. Although, they must’ve had their heyday from the ’20s on.

But anyway, getting back to Lightning. So when it turned out that I was pretty good friends with him, because Mack McCormick had a difficult time getting along with him, as did most people who wanted certain things from him. Although Mack recorded some amazing material by him where Lightning just agreed to sit down and sing about his past and so on, as he did with Sam Charters. But Sam did have to pay him, and he of course made his first LP for the Folkways label that was Sam Charters’, who had found him so to speak, because Mack McCormick apparently had heard about him before, but wasn’t really doing anything with him until Sam kind of made him halfway famous already. Anyway. So when in ’63 the Wawzyns came and hired me to accompany them as kind of a tour guide into the South. I hadn’t really explored it that much. I’d been there the first time in ’59 just to Houston and then in ’60, ’61 and ’62 I went driving through there and making some more recordings I think.

But it was really when Dietrich Wawzyn made this footage of all kinds of really wonderful material, including Lightning. So very soon thereafter I had letters from Horst Lippman in Germany who was producing the annual American Folk Blues Festival along with his partner Fritz Rau, and that became of course a tremendously influential tour that started very modestly in Germany itself and then went into other European countries as they found promoters who would pay for the tour. But again, all of this was largely financed by Joachim Berendt, who was the high priest of jazz in Germany, and he had control over the Southwest German Radio Network, and I think they were beginning to do TV shows at that time as well. So in Europe, you see, the radio and TV people are much more government-sponsored and are very much interested in presenting all kinds of authentic cultures.

So Joachim Berendt really helped Lippman and Rau to organize these and present this material in Europe and by paying them actually well including their roundtrip tickets I think of all these musicians who went. Those were basically financed by the Southwest German Radio Network, or TV. I think they were sort of hooked together. So he talked to me since he found out that I was of German background, and of course realizing that I was Count von Strachwitz, you see, and so on and so forth. So they thought I would be a wonderful guide and see if I can perhaps persuade Lightning Hopkins to go on the next tour. I think that was in ’64 if I’m not mistaken. I think it was largely due to the fact that the French promoter said, “If you cannot get me Lightning Hopkins we can’t carry your package anymore”, because apparently, in France especially, Lightning was really, really popular and that’s why they told Horst, to get him. So Horst met me in Houston, and I told him, “Yeah, you’re going to have to talk to Lightning, because Lightning doesn’t want to fly, he doesn’t like it.”

So we all met, the three of us, Lightning, Horst Lippman and I, in Houston, and I remember the day before Horst arrived, I think Lightning and I were hanging out when he said, “Well, Chris, do you want go hear my cuz?” I said, “Who’s your cuz?” “Oh, my cousin is Clif.” I said, “Clif who?” and he said “Clifton Chenier.” That kind hit a light bulb in my head, because I’d heard a record by him, Ay-Tete Fee. Anyway. Any place Lightning would go I’d love to go too, and that’s how I met Clifton Chenier really, playing at this little tiny beer joint in Frenchtown, because they were somehow related. I think Lightning’s so-called wife was related to Clif. She was a creole too. So she was somehow related to Clifton’s family. So he immediately said, “All right. You’re a record man.” As soon as they see a white guy they figure it must be a record man! Of course, since Lightning introduced me to him, because Lightning had that wonderful reputation of finding other blues singers even to go to Bill Quinn who recorded for Gold Star Records, and I found out that many of those artists living in the Houston area, Quinn got in touch with them because Lightning told him to.

Anyhow so Lightning agreed to go to Europe if I went with him. So Horst agreed to pay my fee for my accompanying Lightning so to speak as kind of an extra musician or whatever you want to call it, and flying over there was really fascinating. That was really one way I really got to know Lightning more so than I ever did when he was just playing at the clubs here. There we would basically talk about, “What are these people doing?”, and whether he was going to get paid right. Anyway. He didn’t seem to worry about that too much.

When he got to Europe it was an amazing trip, because he didn’t like to fly and he knew this was going to be a fairly long one. We flew ok from Houston to New York where we met Air India, you see. In those days there were these hired flights, chartered flights. Air India had I think two airplanes and they would fly to certain places from time-to-time. Anyway. I’ll never forget when we got seated in the Air India airliner, I was sitting next to Lightning, and the personnel, obviously the pilot and the stewards and so on, when they walked in I think they came in from the back, it had a rear entrance, the plane, and Lightning said, “These people are going to fly this airplane?” I said, “Yeah. There’s no problem.” But try to picture his head. They also were East Indians, and the only connection he’s ever had with people of Indian background were the fortune tellers in Louisiana.

Not only Lightning, but I found this out with Clifton’s brother, how strong they believe in all this voodoo and hoodoo business of trying to get a mojo hand. That’s how I learned about what the heck a mojo hand was … I think I was driving through Baton Rouge and I saw a bunch of guys playing cards on the sidewalk. I forgot what they were doing. I just went straight out to them and asked them, “Do you know anything about where I can get a mojo hand?” They looked at me as if I was from outer space. But I figured, Lightning sang about this, “I’ve got to get me a mojo hand so I can fix my woman so she can have no other man.” So the whole thing sort of intrigued me, and I’d seen also the film that Les Blank had made. I think he had made the film about Lightning by then where you had this hoodoo lady, and I remember going to visit her with Les actually. But I asked him, “What is this thing?”

And finally one of them got up and came up to me and said, “Well, you know, you don’t just ask like that.” He compared it to my trying to sell my sister! But then he did tell me it would cost me so much, and at that time I didn’t have a damn penny. So I declined it. But anyway. I slowly realized how powerful that whole, if you can call it a religion, but this belief in voodoo and mojo hands. I always remember the guy. Actually I forgot. I think he was the same guy that came up to me and then he said, “What kind of business are you in?” I said, “Well, I’m trying to be in the record business.” “Well, you don’t need a mojo hand, you need a pull, a pull that will bring the people in, customers into your realm.” Well, anyway. This is how I learned about things. I just became more and more acquainted with Lightning on these different trips, and then he stayed with me.

Then I’ll never forget the time when I had him booked I think in Oakland. In Downtown Oakland in West Oakland there was a black club, a pretty big one, that this guy who kind of controlled the rhythm and blues people who played there, I remember he came up to me one time and said, “I can use that boy.” He was a black guy, and that’s how he referred to Lightning. Well, apparently Lightning played there. That’s right. We had booked him in there and then afterwards this guy came up to me and said, “I can use that boy”, because of that, Lightning never wanted anything more to do with that guy. At the same time I had him also booked at the Savoy Club up in North Richmond, and that was a neat experience. As we walked in, Lightning and I, there was this black woman that also was walking in and she looked at him and said, “Are you the real Lightning Hopkins?” And of course Lightning in his way said, “You better believe it, baby.”

I had an inkling of especially blues musicians who hardly ever traveled, you see. Like in Memphis I first encountered that, I think it was when I was still there with Paul Oliver. Well, the next year I went back to this one bar and I was wondering where I could find Sonny Boy Williamson, and this guy comes out and said, “I am Sonny Boy Williamson.” I said, “No. I think I know what he looks like.” And this guy didn’t look anything like him. Anyway. They were just like you had Blind Boy Fuller number two. Brownie McGhee was billed as Blind Boy Fuller Number Two for a while on his records after the death of Blind Boy Fuller. So a lot of these people who didn’t travel much, but (via their records) were very popular, they had imitators who tried to make a living behind them, and there were obviously people around who were calling themselves Lightning Hopkins, like this Lightning Slim guy. Although he didn’t call himself Lightning Hopkins, he was too smart, but he did call himself Lightning. Although, he certainly never played like Lightning.

Anyways. All these things really intrigued me, and to me Lightning was a really fascinating person. I remember doing to Europe on that Air India flight, of course he got terribly sick, and the doctor we called when we got to Europe, he couldn’t find anything wrong with him. But he literally could not perform for the next week, and thank goodness (a wonderful lady, Stephanie took good care of Lightning!) and the people who were filming the whole thing for the Southwest German TV Network, they put him on the last day of the week that we stayed in Baden-Baden, which was the headquarters of the network. And by that time he finally got over it, but he had I think a total nervous breakdown. He was really that scared on that flight, and he of course made up a song about it as soon as we got there. And when he finally was put on the stage and appeared on the stage after a week in the studio he actually sang that song again that he made up about how he came over on this plane. I asked him once, “How do you make up mosts of your songs?”

He said, “Well, yeah, I just tell them about what’s going on in my head.” But then he said, “A lot of times people also come to me and they bring me like a poem written on a piece of paper, you see.” Like I think this one about picking cotton and something, and he said, “Some woman gave me that”, and of course he didn’t know who she was. So he made a song from that. If you think about it, how people made songs in those very early days of the songsters, just like Mance, he learned a lot of these songs instantly from somebody they heard at a medicine show or some traveling show that came through the little town. And Mance had a fantastic ear to pick this stuff up, and I think Lightning had a very similar tremendous ear for picking up lyrics and then changing them a bit to suit him personally. He told me about those things all along, and of course when I finally made that first …

Not the first album, that was kind of done in the studio in Berkeley, but the next one, the one that had him stand in front of that grocery store that says, “Rabbits for sale”, and so on. There, he asked me, “No, Chris, I don’t want to go to the studio. If you want the real me let’s just go to my room and you record me there.” And that’s what I did, and I talked to him about Tom Moore and all this other slavery stuff. And that’s how he made up those songs that are on that record. Pieces of them he had done before, like Grosebeck Blues and Penitentiary Blues and so on. But he would always sort of personalize everything, which to me was really an extraordinary gift. I think he was simply one of the great poets. I know John Lee Hooker became much more popular, because he could sing, “Boom, Boom, Boom, Boom”, over and over again. Lightning would never do that. He would always make up a song and do that.

I think he was by far the superior poet to almost any of them, and how he could rhyme up stuff on the spot was just beyond me. On some nights when I went to hear him, playing in Houston especially, he would do nothing but boogies. He was in a mood. He was in a real up tempo mood and the people just danced. They were usually attracting very small audiences in these little beer joints. And on other nights he was really in a lowdown blues mood, and sometimes he would sing and then his drummer sometimes, Frenchie, he was a good singer too. I remember, I think I did one session with him. I really liked him, and of course Lightning made up some songs about, “Money taker”, about his woman and she wants to get some money in her hand. Oh well, anyway. I just can’t tell you enough. I was fascinated by this person, because I had never encountered anyone like that, and who was successful at creating a sound that obviously a lot of people really enjoyed.

And it didn’t necessarily mean that he had to repeat the same damn songs over and over, although that did happen whenever, because people, once you start playing for the white folk clubs and so on, they yelled for songs that he had a hit with, or some kind of success with perhaps. Just like Mojo Hand became a pretty big song. That was another weird thing. That was when he went to New York supposedly under exclusive agreement with Candid Records, I think it was. I think Nat Hentoff ran that label if I’m not mistaken. He was supposed to just record for him, and of course Lightning somehow was met by Bobby Robinson, a black man who had the Fire and Fury record labels. He probably said, “Yeah, man, I’ll pay you what you want if you come over and make a record for me.” Well, the one he did for Bobby Robinson was Mojo Hand, and that became a real good seller.

And I remember then Mack McCormick, he called or wrote to me, “Chris, when did he record this? When did that happen?” I said, “Well, I believe it happened when he was on that trip to New York, sine that’s where it was recorded. Oh God, because all these record labels were very tee’d off when they thought they had some kind of an exclusive like Candid and Nat Hentoff thought they did. They didn’t know Lightning. Lightning did whatever Lightning wanted to do. I don’t think he ever signed any of these contracts. He may have but anyway. These people thought they had something. Anyway. I thought he was an incredibly bright person and emotional at the same time, and I think he was one of the most unique blues singers ever. Some of them were more intense, sure, but I think Lightning could be just as intense. For example, that record he did, I’m Achin’ All Over, that is just ferocious on the Herald label. “I’m Achin’ All Over, I believe I got the pneumonia this time.”

Tom Diamant:

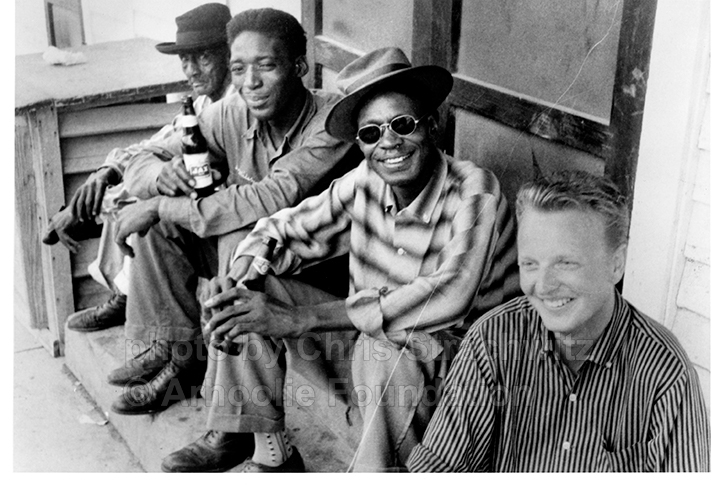

Tell about the photo that you mentioned earlier with Lightning in front of the grocery store and there’s kind of a delivery van in back there and it’s got the, “We sell rabbits”, and that kind of thing. Whose idea was that to take?

Chris Strachwitz:

He told me not to go to a studio that day. He said, “Come on into my room”, and there was this grocery store just across the street. So I just said, “Lightning, I’ll just take your picture right here, you’re looking good.” So I just took his pictures there. I’m not sure if I was really aware of what was written all over, but it was just this nice funky little local grocery store, and you can see how he was really feeling good about what he did that day. It was at the end of the little session that we did in his room, and where I had put one mic in front his amp – that I’d learned from Bob Geddins how to record amplified guitars. And the other mic in front of his voice. That was that two track big Magnecord machine that I lugged around at that time. That was a good record.

Tom Diamant:

You did a recording with the Hopkins brothers, Lightning and his brothers. Tell me about that.

Chris Strachwitz:

Well now, Lightning always told me about, and I knew that Mack McCormick had met his brother Joel Hopkins, who was a real basic, very much more like Blind Lemon, kind of singer. And then I think at one of my visits, I forgot when it was, he must’ve told me, “You know”, he said, “I heard from my older brother, John Henry Hopkins, and apparently he’s out of the penitentiary and he’s living up in (Waxahachie, TX). Anyway. I decided, “Okay, Lightning.” And he told me about how so many people thought that his older brother was really the better songster and most amazing guitar player in his day. I don’t remember how much older he was than Lightning, but Lightning thought a lot of him. Unfortunately, when we got there the guy was just living in utter poverty and just literally in a shack, and I guess there was electricity, because I did plug in my recorder. But they all started drinking, you see. That was the real problem.

And I’ve never seen Lightning be that mean, especially to a relative like John Henry. Like at the end of the session I gave them all some money that I told them I would. I forgot what it was. Maybe 200 or something for each of them. I think Joel was riding with me and I think Lightning was driving in front of us with his mother up to … Was it Waxahachie? And he was obviously in pretty bad shape, the poor guy, this John Henry Hopkins. And since he had hardly anything to eat as far as I could tell, and they started drinking, well, I think it was amazing that I got anything out of any of them. And of course Lightning really got mean towards him when I gave him the money, and Lightning started grabbing the money that I was giving to John Henry and just said, “Come on, you owe me that from way back.” I couldn’t believe it. He knew the guy didn’t have a pot to piss in, and he took half of it away from him. I forgot what it was.

But I thought that was the only time I ever seen Lightning expressing a real mean streak towards someone, especially since he wanted to do this. But people are hard to figure out. Then I think Joel, I think I actually recorded him separately for the track that’s on there, because he sounded really bad, on that trip anyways. Yeah, that was quite an adventure I must say. And then Lightning wasn’t really that sure about where that little shack was that he was staying at, but somehow he found it just like Fred McDowell found that shack in the middle of the woods of Eli Green that he took me to that amazing day that happened in Mississippi. But anyways. Yeah, that’s pretty much all I can remember of that adventure. I thought it would be great to do the Hopkins family together, somehow, because that’s what it was.

Tom Diamant:

Were you in contact with him pretty much through the rest of his life?

Chris Strachwitz:

No, I didn’t. I didn’t stay in touch with him that much towards the end. I think I remember going to see him in San Francisco when he was presented there, but I was no longer his host, so to speak. I forgot who actually he was staying with … No, I didn’t really stay that close, because I had so much other musicians to deal with. So that sort of faded from my … And he had made so many records. I just remember that Bill Graham I think hired him at the Fillmore, but I really don’t remember all those details. I don’t think I went to his funeral. I feel bad about it, but I did go to Clifton’s funeral, I remember that. I didn’t keep track of poor Lightning towards the end, sorry to say. But he was an extraordinary person, absolutely.

Tom Diamant:

It’s amazing that you didn’t just record these guys. They stayed at your house. You traveled with them. Sometimes you stayed at their house. You really got to get a pretty in-depth feel about some of these musicians.

Chris Strachwitz:

Yeah, correct. And I know Lightning stayed at my house in Berkeley once I got that house. I got that house in ’64 or something, so maybe ’65 even. I remember he slept in my guestroom. (One time he brought Annette with him and I had both at my house). Oh, Lightning always liked to go to the horse races. I think I remember we went to Golden Gate Park and he was really keen to watch the ponies run. Like he made up some songs. And also he loved to fish. I remember going with Lightning on the Berkeley Pier out there, but I don’t think he caught anything. We had some interesting times together, I must say. I think he was intrigued by the way we lived, that is me and my friends in Berkeley, as much as I was interested in how he functioned and his people lived. It was sort of a really amazing interchange of experiences.